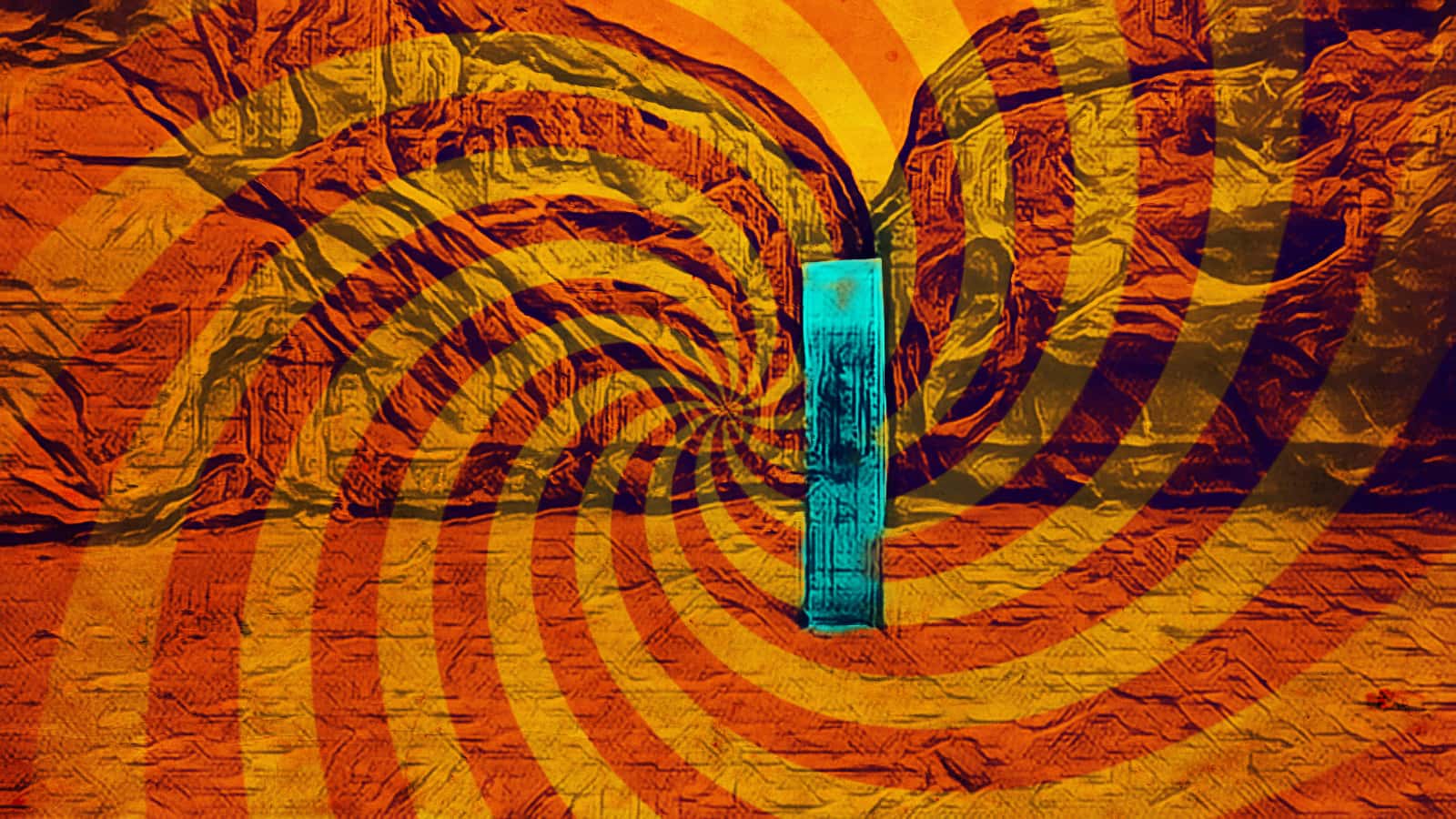

It’s been a month since that mystifying metal shaft called the Monolith was discovered in the desert by some Utah wildlife officials, who were out counting sheep by helicopter.

The discovery went viral around the world and within hours Internet sleuths had discovered the coordinates of the Monolith’s location and posted them on Reddit.

A mad dash of selfie seekers congregated in this remote location to see the Monolith for themselves.

Over the next few days, the hordes trashed this previously pristine corner of Utah—eroding fragile soils with footprints and tires, and establishing a minefield of toilet paper and fire pits in the vicinity.

Four days later, a group of Moab locals including Sketchy Andy Lewis, Sylvan Christensen, Homer Manson, and another anonymous figure took it upon themselves to tear the Monolith down. Their justification was to protect wilderness, a charge that many pointed out was hypocritical since Sketchy Andy, in particular, is known for installing his own—albeit temporary—public art pieces such as his infamous Sky Net, which is a airy spider’s web of colorful high-lines and webbing from which BASE jumpers chill and jump.

The idea of what constitutes public art, and who gets to determine its fate, is an interesting question that has obvious parallels for us as climbers. The Monolith certainly isn’t the first piece of metal to be installed on public lands without any kind of official permission, and which subsequently brings hordes of people. As climbers, we feel totally entitled to install our own bolts in rocks on BLM lands across the West. It’s not a coincidence that many of us refer to the establishment of rock climbs as an “artistic” endeavor.

I’ve heard scold-happy traditionalists argue that bolts and chalk in a piece of rock are inherently unsightly and ugly. I disagree. A piece of rock covered in chalk and bolts can be a beautiful and mesmerizing sight—a large-format painting that fails to avert my attention as I try to decipher the sequence above. It should go without saying, of course, that not every painting is worthwhile or interesting, and likewise not all bolts and chalk are inherently or automatically good, let alone justifiable.

Beyond the obvious differences in size and scale of attention received by the Monolith, there is no meaningful ethical distinction between the installation of the Monolith and the installation of our bolts, thousands of them across Utah alone. In some strange way, this is our public art.

I find Sketchy Andy’s justification for chopping the Monolith to be, well, sketchy at best. If I went out and chopped Andy’s next Sky Net under the same pretense of environmental vigilantism, there’s no way that he and his crew wouldn’t receive that act as anything less than a declaration of war. This hypocrisy rubs me the wrong way. These are people who claim to stand for extreme freedom of expression and celebration of individuality, but by destroying something that wasn’t their’s to destroy, they’ve revealed the limits of their tolerance for those ideals.

Art is most compelling when it becomes a window or mirror into a cultural moment. Although the Monolith is gone, its fast and savage journey into the hands of BLM officials is now as intrinsic to the Monolith’s meaning and purpose as the Monolith was itself. I don’t know what the original artist or artists intended to say about our culture and society when they decided to drill this piece of metal into a backcountry rock in Utah. But what it now represents is a story of how selfish and disrespectful we all can be.

The lack of respect shown by the hordes of visitors leaving toilet paper all over the place. The selfishness of needing to be that influencer who gets that photo for your Instagram feed that will get you a few more likes and followers. The vigilante’s lack of respect for a vision of art that wasn’t their own.

I loved the Monolith because of its purity—the artist who created it without any fanfare, no big gallery opening filled with champagne sipping snobs with their checkbooks open. Is it ironic? Is it a joke? Maybe. Or maybe it was meant to bestow a bit of inspiration and wonder in the visitor who stumbled upon it during an acid-fueled vision question in the desert.

That this purity was corrupted so quickly, so viciously, an so completely, is the story of our time. And perhaps in a similar way, it’s the same story that’s unfolding at all of our crags.

This piece originally appeared as an audio recording in paywalled episode of The RunOut Podcast. You can become a Rope Gun and support our podcast on Patreon.

I’m assuming some, not all, climbing bolts placed in Utah are done so perfectly legally. The ethical distinction I see is whether or not one is acting in bounds of the law. There’s an ethical argument to be made for playing by the rules. Whether or not one cares about said distinction is up to their own ethical framework, but the distinction is there nonetheless. Perhaps you thought of this, but considered it not “meaningful”. Perhaps you didn’t consider it.

(My opinions)-Should land managers have taken it upon themselves to remove the Monolith? Yes. Was it illegal for Andy and crew to remove it? No. Are they vigilantes if they broke no laws? Not in the legal sense. Would you have felt better about the removal had it been by a group free of any perceivable hypocrisy? Based on this article, I would guess yes. However, nobody stepped up, and it seems Andy and crew do truly care from an environmental perspective.

It took climbing a long time to move out of the legal grey area in regards to permanent anchors being left on public land. I’m guessing highlining is largely still in that grey area (or worse), especially when it comes to placing bolts specifically for highlining. Demonstrating that the user group cares about minimizing environmental impact might be an important thing for the leaders of that community to do if they aspire to be promoted out of the grey area. Beyond their subjective visual impact, highlines and space nets do no more environmental damage than climbing. Maybe less.

Artistic purity of the Monolith aside, maybe the artists should have considered that the location of their installation was in an extremely ecologically sensitive area. Regardless, when it was time to clean up the resulting mess it wasn’t the artists who stepped up… or was it?

Erase the lightning bolt

What could be more beautiful than a thought process that challenges another to use their mind, body and shear determination (spirit) to ascend towards the heavens? How could it not be art?