I live in Western Colorado and have a view from my house in New Castle of a geological formation called the Grand Hogback, a spiny 70-mile long ridge that demarcates the line between the Colorado plateau to the west and the Southern Rocky Mountains to the east. I love looking at the Hogback, and admiring the way this fluted ridge plays with shadow and color depending on the time of day or season.

As of last year, our local mountain-biking organization got approval to install a switchback trail up what was formerly a pristine face on the Hogback. They’re not the first humans to tread up this ridge, however. New Castle used to be a mining town and there are many old mines up on the Hogback. Methane explosions in the coal mines killed over a hundred men, however, about a hundred years ago, which put an end to mining activity in the area. Some of the mines, strangely, are still on fire over a century later—which is why one prominent high point on this Hogback ridge is called Burning Mountain.

The biking trail up Burning Mountain is an eye sore. I’m not a mountain biker myself, but I’m considering getting into it, in part because I am now forced to look at this trail every day and it reminds me that New Castle, in addition to being in close proximity to a lifetime of awesome rock climbing, is also a mountain biking hub. But as a rock climber, I find myself pondering the differences between what kind of “impacts” are either openly tolerated or vehemently pooh-poohed within the climbing world versus those that are seemingly embraced by the biking world. Not being part of the biking community here, however, I can’t say that there’s no internal conflict over the aesthetic or ethical impacts of carving a very visible biking trail up a formerly virgin face, but from a distance it doesn’t seem like bikers really give much of a shit about these things.

Climbers might be a special breed on this count. We’re highly concerned about the “impacts” on Wilderness that something like a little half-inch bolt imparts on the landscape and many within our community seem to think that our fellow climbers ought to commit seppuku if they trample across cryptobiotic soil in places like Indian Creek, where cattle have been trampling the crypto for more than a century.

I tend to think these concerns are not just overblown, but at least in the case of bolts, are outright wrong, as I recently argued in this piece. These kinds of internecine conversations within the climbing world seem especially ridiculous when you look at how other outdoor sports communities regard their own special rights to recreate on the land. This biking trail, once again, is a glaring eyesore carving its way up a mountainside that everyone in our town now is forced to look at. But when I hike beneath any of the many backcountry limestone cliffs surrounding our town, even with my own trained eyes, I can’t see any bolts or even chalk. They just look like unmolested rocks, out in the wild, even though they’re actually studded to the nines with stainless steel.

Despite the visual impacts of this biking trail, I’m not against it, per se, mostly because I can understand by way of empathetic logic the fact that this trail will bring joy and meaning and opportunity to many bikers in our community. And who knows, maybe I’ll be among them at some point as well.

There is this personality type in climbing, however, that seizes any opportunity it can find to tell everyone else that they shouldn’t be climbing. The grounds for justifying their cop-like behavior change but often invoke one kind of ethical justification or another, often from environmental to access to weather concerns. The most classic example of this, perhaps, are the “wet-rock police” of Indian Creek who scold anyone who dares set foot beneath a splitter 48 hours after the last drop of rain fell from the sky.

This is not to say that it’s automatically fine to climb rock, particularly sandstone, after it rains. It may not be wise, especially in areas with friable, featured sandstone like Red Rocks. Rocks break in climbing and they may be more likely to break if they’re soaking wet. But the notion that a perfect splitter might be somehow damaged by an ascent after a light rainfall is lunacy and just not grounded in reality.

There are all kinds of what-ifs one whips up in an argument like this. But what if the rock is wet and you’re whipping on cams: the cam lobes could gouge out the rock and leave permanent scars, or the cams could fail and you could die! OK, maybe that’s true or maybe it’s not. My personal opinion is that people should be free to use their own discretion and make smart and good choices, which invariably means that a small number of idiots will do an Oops every now and again and make the wrong choice.

But to me this is always better than having a bunch of cops running around, feeling virtuously empowered to scold everyone around them for not following what are actually arbitrary rules, such as waiting 48 hours after it rains to climb.

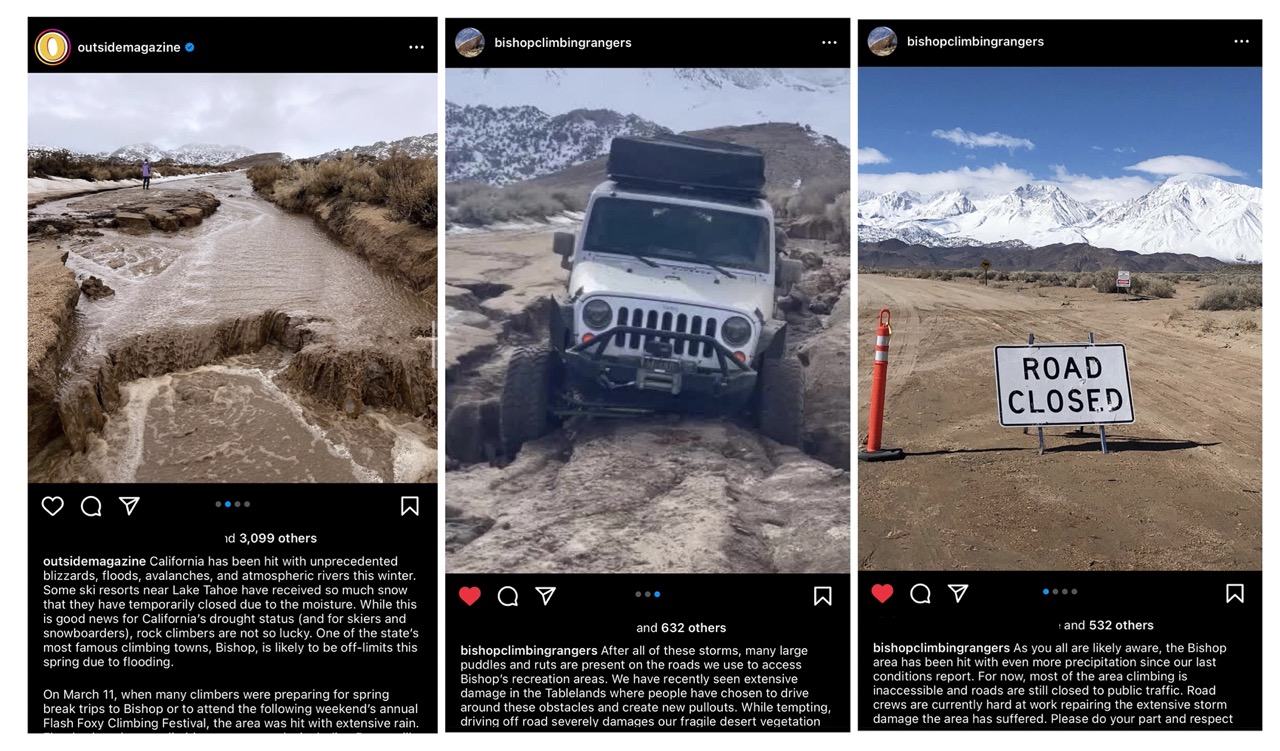

You may have seen some of this kind of behavior if you tried to climb in Bishop this spring. A big snow year and spring rain caused road damage that scared many climbers away from visiting one of the most popular spring-break bouldering destinations in the country. But according to at least one first-hand report I received, the damage was overblown and not a big deal, especially when compared to neurotic and panic-stricken admonishments that were dished out on Instagram by some climbers, including the mainstream climbing media channels. This climber writes:

Because of the deluge of washout pictures being splashed all over Instagram, we were fearing the worst, but we decided to still go and ski mammoth plus maybe hike into some of the bouldering.

We followed the recommendations of the @BishopClimbingRangers and were able to park 1.5 miles from the Buttermilks or in the back parking area of the Sads and hike in no problem.

The washout on Buttermilk Rd. was minor enough that some people were driving through it in their minivans even as Climbing magazine and the other Bishop accounts posted weeks-old photos of flooded roads. (We still parked per the climbing ranger recommendations and walked, but it would have been easy to drive through.)

Even more absurd was the situation on Chalk Bluff Rd near the Happies/Sads. This road is still closed by LA water dept., even though it is in pristine condition; it was repaired as of April 1, and was as good for driving as I’ve ever seen that road. Again, we still walked in, but it was super drive-able. I don’t know how we as a community can advocate to LA water dept (who took this land/water from natives in the first place) to open these roads, but the closures seem excessive.

Don’t really have a thesis on this situation except to say the online panic and scolding seemed pretty over the top to our group. And many of the Bishop businesses that rely on climbers were probably hit hard as a result. The conditions for anyone still making the trip was great—I’ve never seen the climbing areas as empty as they were, but it struck us as a little bit gatekeeping/”locals only” kind of phenomenon.

Instagram vs. reality:

I don’t have much of thesis either, but to reaffirm this person’s observation that this kind of cop-like behavior is pervasive in climbing. We saw a lot of this kind of moralizing fretfulness in the early months of the pandemic, in which many people had come to accept the idea that you shouldn’t ever go outside, especially for something as non-essential as rock climbing—unless you’re a local, that is.

What is the psychology of climbing scolds all about? I think it stems from a genuine sense of wanting to be a good member of the tribe and therefore worthy of inclusion in the group. Anyone who places themselves and their own selfish desires to climb above all other concerns should rightfully be sanctioned with ridicule and criticism. To be the person who calls someone out for that kind of behavior often elevates them as a moral leader within the community, so incentives abound.

These dynamics are as old as neanderthals, and I can see times when they serve an important and necessary social purpose. It’s just that … not every reason we’re given as to why we shouldn’t climb here, climb now, use this approach, place a bolt here, and so forth, is a good reason! Sometimes—often, even—we’re told not to climb for objectively bad reasons that make no sense.

People who think critically, and who have disagreeable personality types, are often the ones to point out the fact that these rationales are bad. And people who lack these faculties and/or personalty flaws, therefore, are the ones who are prone to becoming the scolds. (OK, how’s that for a thesis?)

Is there more to say about these kinds of hall monitors roaming the climbing world, looking for any reason at all to stop other people from climbing, and even controlling how they think about climbing—i.e., what language they use, whether or not they make the right land acknowledgement in their Instagram spray-post, and so on? I think it’s clear that there is also an element of resentment that underpins much of their righteous sanctimony. Perhaps their resentment stems from basic jealousy of the idea that someone out there is climbing when perhaps they themselves can’t. Perhaps they have a job—or perhaps they’re just not good enough. Pro climbers in particular are often the targets for a lot of this simmering bitterness for reasons that should be obvious.

I don’t have any profound conclusions here. When the reasons and rationale for why people shouldn’t climb are bad and don’t make much sense, those reasons should be questioned. Scolding and shaming can be useful and important tools when used for the right reasons—especially in a community that’s largely self-regulated. But I think sometimes this goes too far, especially now as we live in a culture that seems to celebrate every and any kind of expression of virtue signaling over all else. But at some point, you’re not being virtuous. You’re just a cop with Instagram.

As of this last winter, Hueco Tanks now has an official policy to prohibit climbing in the park after rain and snow. Thanks to the kind of online virtue signaling discussed in this article, climbers literally handed the decision of when you get to climb or not over to the cops. The important observation here is that the park staff at Hueco (and other popular climbing areas I would assume) pay attention to what climbers are talking about and posting online. My take as someone who lived in the area for years is that it was definitely fueled by a locals only type attitude, and that deep satisfaction that can only come from calling out and reposting call outs on your favorite social media platforms.

That’s a great example. thanks for the comment Jake

I found this somewhat bizarre when I was in Hueco this winter. The park staff are certainly knowledgeable about the park, but seemed to have little awareness of (or interest in) the subtleties that should matter when determining if it’s OK to climb. South facing climbs made up of slopers are obviously different from Nobody, as an example. But it was just a blanket “no climbing today.” I understand the push to avoid nuance as a result of the sheer number of interest parties… but this no-context thinking just obviously leads to further rule breaking and pseudo policing.

Beautifully written, Andrew. Love your insights regarding this interesting phenomenon. After 8 years of full time climbing/travel, we (Mags & me) have come to the conclusion that it’s best to lead by example & let others chose their own path. They’ll either figure it out, or they won’t. Ultimately, trying to control anything, or anyone, is an illusion.