From my vantage beneath a steep bouldering wall at the Movement climbing gym, called by some “the best crag in Boulder,” I sat hypnotized by the sight of a tight little package, all hot with hair full of body and bounce, pumping an elliptical machine. I enjoyed this nice moment until the guy (jerk) next to her diverted my attention.

I couldn’t tell if he was working the machine, or if the machine was working him. He was the rubbery ligament to the elliptical’s cranking elbow joint. His head jutted forward, accentuating his underbite, and his back hunched as if he carried a turtle shell. He was trying really, really hard. I recited out loud the thoughts I imagined he might be having, matched to the tempo of his earnest workout seizure.

I’m gonna get BIG!

I’m gonna get STRONG!

People are gonna LIKE ME!

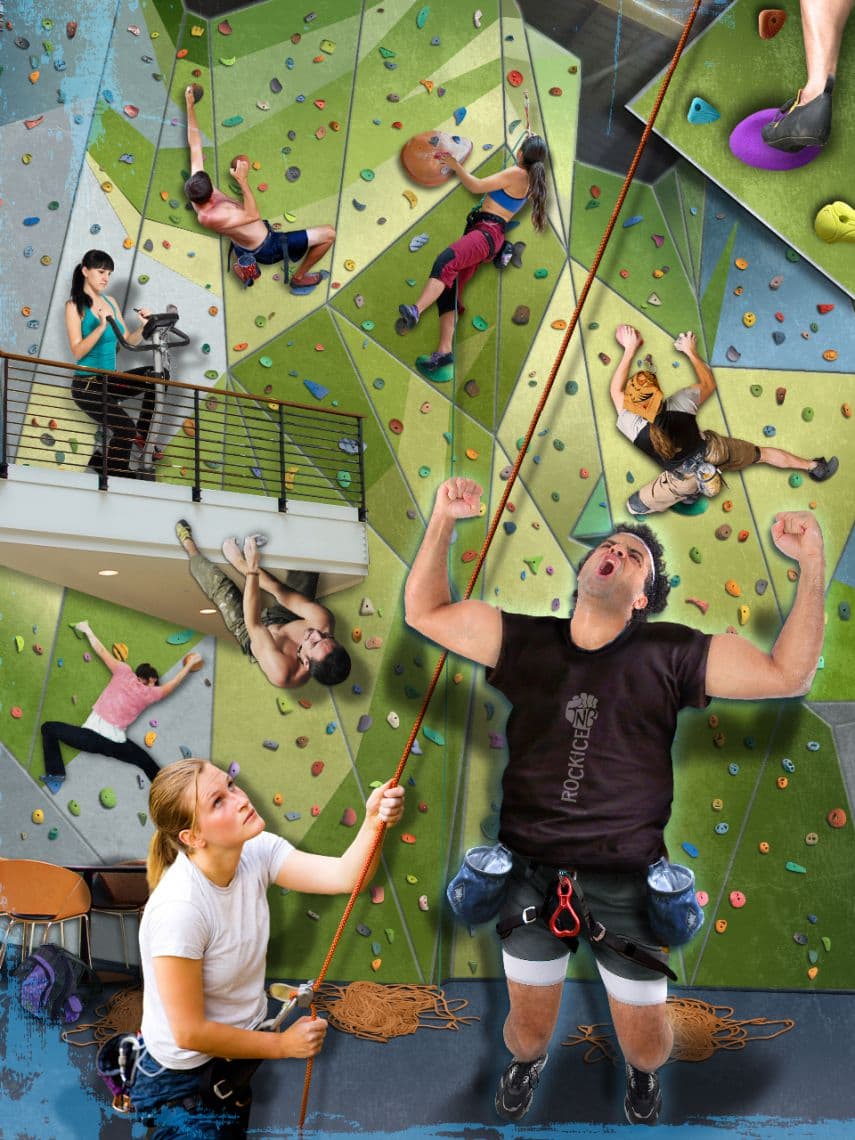

My friend Dave cackled cruelly. Gyms are funny. We were in a microcosm of normal life, replete with the same existential dilemmas concerning how we spend our time. There’s nothing better than watching all the absurd things that people do, and thinking about whether any of it really makes a difference. Will climbing on plastic translate to getting better at climbing outside, the climbing that actually matters? (Technically, outdoor climbing also doesn’t matter, but never mind that).

We watched a skinny, pimply kid, of 15 or 16 go bonkers in the weight room. His ignorance for proper form was only surpassed by his enthusiasm for moving the heaviest possible thing he could find.

Joe Kinder darted up a V1 warm-up problem like a pouncing panther. He jumped, landed on the mat and puffed his chest. “Still got it,” he declared. Joe’s 30 now. He’s proud that he can still climb so well in his “old” age—which isn’t that much of an exaggeration when you look at all the kids with half as many years, climbing nearly as well.

A ray of midday sunlight found its way through a window into the gym. It was perfectly nice outside. The trapezoidal block of light highlighted one corner of the bouldering wall, where a male climber stood, milking a no-hands in full-splay stemming position, six inches off the blue mats. He was wearing a halter-top and sported two chalk bags, one on each side like gun holsters, a totem to John Sherman that I instantly recognized and admired for its superfluity. He chalked both hands simultaneously, though for what reason I doubt even he could say.

The climbing gym is the watering hole: a place where all the little creatures of our climbing kingdom come to frolic, play, swagger, sashay, find mates and throw feces. It’s a meat market. A dojo. Occasionally, a dance club. A training ground. A proving ground. A one-upping ground. A place where everyone knows your name. It’s also a place where many of us now spend a majority of our climbing life while maintaining that our time there has nothing to do with why we call ourselves climbers. The gym is so real, but at the same time, it’s not real at all.

Yet nothing else has had a more deviously profound effect on what it means to be a climber. Over the last 25 years, the gym has slowly altered our perceptions of convenience, and route and move aesthetics; made mutants of our children; aided in raising standards; and been a catalyst for hundreds of thousands to the outdoors. It is the single most influential aspect of today’s climbing culture. Maybe we should talk about it.

I don’t want to go into some tired elegy for the bygone days of no climbing gyms. (For that and other recurring hits—including gumby-bashing, retired-climber self-affirmation, and a great compendium of overly complicated, often dangerous directions to procedures like belaying, leading, cleaning, jugging and hauling—please visit any online climbing forum.)

Also, I don’t feel like commenting on whether the “kids coming out of climbing gyms” will have the right set of ethics to earn their forefathers’ respect. Plenty of kids have come out of gyms and gone on to slay the gnar in good style, just as plenty of gym-bred weenies go on to act like total fart-breathers at Red Rock’s Gallery, ruining everyone’s good time with their loud swagger, while simultaneously teetering on the verge of an accident due to sheer ignorance. Anyway, I’m pretty sure both types existed before gyms.

Gym culture, however, has its own idiosyncrasies that set it apart from other forms of climbing. Certainly my favorite is the Belay Test, which is sort of like a climbers’ Bar Mitzvah. In this Jewish ceremony a boy at age 13 finally becomes responsible, in the eyes of the community elders, for his actions. In this case, the adolescents are climbers and the elders are the gym owners, who live in perpetual fear that they might be sued.

Everyone takes the Belay Test, and if they don’t pass, they remain in a state of arrested development, doomed to boulder like children until one day managing to grow up and catch a lead fall like an adult.

As an award-winning author of an award-winning book that teaches how to belay and lead climb properly, I always feel funny taking the Belay Test. It’s not that I feel “above” it (I am), it’s that I hate it when people watch me do anything, especially something that I could do in my sleep (which, basically, I have: during one partner’s four-hour aid lead).

Fortunately, Belay Tests are all basically the same, so I know what to expect. First your partner climbs, while you belay; then you switch roles. Normally, the gym has reserved one particular route for the Belay Test, and it is usually rated something farcical like 5.9, even though if it were outdoors mountain goats would be standing all over the holds. Meanwhile, a designated gym employee monitors you, absolutely basking in this rare moment of power like he’s the cop, and you are the illegal immigrant with a pocket full of llello.

If you try to do something “weird,” like tie in with a double bowline or belay left-handed, it throws the tester into a fit that won’t stop until you do something that looks familiar to him. And you just have to do what he says because it’s easier than arguing. But that doesn’t mean you can’t tip the balance of power by screwing with the tester.

If I have to belay before my friend, I thread my Grigri 2 with the rope normally, but then grab both sides of the rope and start jerking back and forth on them. Then I say something dumb, like, “Hey, it works BOTH ways!”

Preferably, though, I get to climb first. As I tie in, I play it real cool so neither my partner nor the person testing me suspects anything. Theatrically, I ask if I am on belay and if I have everyone’s permission to climb (PLEASE?!). Then I step onto the wall and launch the largest double-handed dyno I think I can possibly stick.

“Woohoo, this route is SICK!” I say, flashing the shaka sign down to the wide-eyed tester, who by this point has taken a crouched position, fully locking down his back-up belay. The tester passes me just so he doesn’t ever have to give me a Belay Test again.

Another fun thing to do in gyms is the Chain of Shame, which essentially is a close cousin to pool shark. Everyone has done this, and all of you already know exactly what I’m talking about. Anyway, to be clear, the Chain of Shame involves watching some boulderer work on a problem that is obviously hard for him or her. You realize that a) you’ve already done that problem but this climber doesn’t know that, or b) you are pretty certain you can flash it. Upon recognizing this climber as your unwitting prey, you have trouble containing the wicked grin that soon spreads across your face.

You stroll up to this schlemiel, this rube, and sit and watch him or her climb for a minute. Maybe you try something else first, so as not to be too obvious. Then, as your victim flails once more, you pretend to be courteous, asking permission, which, by the way, is a truly bizarre bit of bouldering etiquette. (Has anyone ever said no?)

“Do you mind if I try this with you?” (Beware if you ever hear this!)

The climber will say, “Of course, go right ahead.” Then you smoke that problem and drop down onto the mat and say something modest like, “Wow, that was cool,” which really means, “Wow, I can’t believe how much better I am at climbing than you.”

With each problem you dispatch, you can feel the power of your ego grow while that of your enemy dwindles. Basically these are the same rules as Highlander, only the Chain of Shame works in reverse. Once you’ve slain someone, it’s this person who advances on to find someone dumber and weaker than he to dominate.

Recently, I went to Atlanta’s Stone Summit, the newest, biggest gym in the country. Because I don’t live anywhere cool, I’m used to training on dingy garage walls and also a high-school woody that is in a basketball gym (where Tuesday Night Bouldering—the real-life event, not this column—involves the objective danger of dodging errant high-speed soccer balls). But Stone Summit, to borrow a word from the realm of outdoor climbing, is a destination.

Officially, I was in the Dirty over the holidays to check out what may be the best bouldering in the U.S. Unofficially, I was equally excited to climb at Stone Summit.

Checking my messages that morning, I read a forwarded e-mail to the magazine. A self-described old guy was taking us to task for printing controversial articles that challenged his way of thinking, and as I drove to the gym, this note lingered glumly in my head. I wondered if climbers’ dogmas and ideologies would be quagmires that would undermine the roots of our sport, and its potential for growth, for as long as climbing exists. In 50 years, will we still be citing the Bachar-Yerian, Ron Kauk, top-down, ground-up, et al. and will the radio still be playing “Don’t Fear the Reaper” and classic rock?

Upon arriving at Stone Summit, I was immediately in awe—though to be clear, it was nothing like the first time I saw El Cap, or the Southern Alps or even the Motherlode. It was a different type of wonder, a man-made wonder, which I was neither above nor below appreciating. Compared to the rinky-dink indoor walls of the 1990s—climb a dead vertical panel to a dead horizontal roof (sucks)—Stone Summit has the grandeur of a modern-day Coliseum.

Standing in a long line to buy my ticket, I felt a bit exuberant, like a kid, not quite recognizing that here climbing had been combined with Disney World. In fact, 650 people were in the gym that day—most of them kids on high-school teams (Team Texas, Team Illinois) who had traveled with their coaches specifically to train here during the holiday week.

After passing the Belay Test (stuck the double-dyno!), I scurried over to the lead wall and tied in for a 5.11. It was the first place I ever climbed indoors where climbing actually felt similar to the experience outside. Unlike most lead walls, which are straight-angle sprint fests, or dumb short bulges, this wall was tall (55 feet) with well-designed angle changes that forced you to stop and shake mid-route, and created opportunities for multiple cruxes. Unlike most walls, where the routes get harder because worse slopers are set farther apart, these routes built on themselves. Like “real” routes. Here you could set true 5.14s and maybe even 5.15s that weren’t “dumb.”

There were still all the same funny and absurd sights of people working out—hotties on ellipticals; the guy who carries multiple locking carabiners on his harness and has the “Daisy Chain G-String” flossing his crotch[1], and so on.

Yet I also saw another side of the indoor experience. The number of levels that must come together for any gym to work gave me a whole new respect for indoor climbing, and had me wondering how far it can be pushed. The first level is the wall itself. An architect designs the walls, envisioning all the angles and features that lend themselves to an enjoyable, challenging, useful climbing experience that must parallel nature.

Climbing holds make up the second level. From sharp uncomfortable stones drilled into home woodies, to the incredibly imaginative polyurethane shapes of today, climbing holds have come a very long way. They are crucial to whether we enjoy or hate a route.

On the third level is the route setter, who uses vision and creativity to bring the work completed in the first two levels to life.

The final level is the climber, whose interaction brings meaning to all the prior stages of work. Even the climber’s style can be recognized as art, like a performance. There is nothing real about indoor climbing, yet it’s simultaneously so real.

None of this would be possible if all the artists weren’t inspired by the organic patterns and shapes of the natural vertical world. No matter how good indoor gyms become, our goals, aesthetics and values as climbers must remain firmly rooted in the outdoor world.

Above all else, the climbing teams I got to see that day at Stone Summit impressed me most. They filled me with pride and even envy. Some of the kids were really good, lapping 5.12 and 5.13. A lot of them, however, were working on 5.10 and completely psyched about their projects. None of them were screwing around, and none of them had attitudes or negative preconceptions. They were leading and belaying each other well, and projecting in good style. By the end of the day, I had forgotten about the old guy’s letter, dismissed it as irrelevant. The future looked pretty good to me.

This article originally appeared in Tuesday Night Bouldering, Rock and Ice 194. Please click here to subscribe to the only magazine run and built, with love, by climbers.

If this were a paper article I probably would have torn at it in anger before the finish. I only started climbing a year and a half ago and I admit, most of my climbs have been in the gym. So, reading such disparaging things about the rock gym, how you look down upon the belay test (Sorry but i feel better knowing anyone belaying me has passed a modicum of scrutiny) and the perpetuating of the gym a-hole (What you call the Chain of Shame) made me want to scream. Maybe I’m lucky. Maybe i happened into the best gym on the best days with the best people. My gym experience has always been filled with positive attitudes. Even working on a V1 that highlights a weak point in my climbing, struggling with it, the regulars (of which I have become a part of) are always cheering you on, telling you “you’ll get it” You hear cheering, you feel the energy as they encourage you to get better. Are there the gym a-holes, of course, but people tend to ignore them, don’t talk to them, don’t cheer them and merely look on in the “Yes, we all know your good, no reason to be a dick about it” smirks on their faces. People struggle, they get asked if they would like some beta. People who screw around are not well tolerated, they get told they are being dangerous to themselves and others, they don’t return often. So I’m very happy you have finally had a good experience at an in-doors facility. When climbing outside is a hike you don’t have the day to take, indoor climbing can provide a good place to increase endurance, power, and technique.

If only the gym could increase your sense of humor.

I absolutely loved this piece. I’m definitely what’s known as a “gym rat”, one of those “kids” (I’m not a kid anymore, but I’ve only been climbing for two years or so) that trains hard in the gym and then takes it outside. I’m lucky enough to work and climb at one of the best gyms in the country, Earth Treks Rockville (which, by the way, you should come check out sometime). Earth Treks is blessed with great walls, amazing setting, and a truly wonderful and supportive community. I’ve been to plenty of other gyms throughout the country, and I can say all gyms aren’t created equal.

I agree that we should be focused on the outdoor side of things more than inside (plastic is plastic…it’s great to train on, great to gather around, but touching real rock is a whole different ballgame). it’s great to train hard and send that blue V8, but that climb’s gonna be gone in 2 months…it’s certainly a little more rewarding to train hard inside, get outside, and send that classic problem that’s gonna be around forever (relatively speaking).

we’re definitely in an age where gyms aren’t going to be leaving us anytime soon. recently, we’ve seen some of the strongest climbers grow up in gyms, then get outside and really push the limits (for example, Sasha, an ET climber herself). it’s great being able to learn how to do things safely in a controlled environment, being able to train yourself physically and mentally, and it’s just so damned convenient sometimes. for people like me who work 2 jobs, 7 days a week, and live 4+ hours from any *real* climbing, it’s great to be able to climb 4 or 5 days a week.

anyways – that was rambling. loved the piece, keep it up.

Excellent writing AB. Even better the second time around!!

Long but nice writing, read it in a breeze!

A comment on the Chain of Shame: some time ago I was so deeply involved in solving a bouldering problem by myself, so psyched, that several times people came by to “try it” and I just turned my back or walked around the corner, not to see how they did it…

A bunch of attempts later, it was like I managed to put all my strength and all the technique I had acquired to date into that problem! It felt really really good to have finished it on my own!

“…even though if it were outdoors mountain goats would be standing all over the holds.”

this made me laugh hard, thanks!

Love it! Witty, well written, and insightful. I appreciate your ability to take a step back and give some perspective to life and climbing. Thanks!

this article was pretty well written but as someone who works in a climbing gym, the belay test is necessary for insurance and safety purposes. None of us actually want to give it, we’d rather be hanging out with people we’re friends with or answering questions from people new to climbing. The fact you take it upon yourself to try and “terrorize” the employee and that you think you’re being looked down upon is baffling. Speaking only for my self but I feel its safe to assume most people who work at climbing gyms do so because they love climbing and want to be involved with it at all times (not to mention the fact its easy to take off work for trips) so take it easy on us, we love climbing just as much as you.