Climbers find listening to beta—information about how to climb a route best—annoying, or to be more accurate, they find the person perpetually giving out the beta annoying, even though this person may be just trying to help.

It’s odd to find good advice irksome, but I suppose it’s not surprising if you think about all the other things climbers do as ways of self-sabotaging our enjoyment of, or success in, this sport: e.g., climbing with significant others who don’t really like climbing; wearing socks under shoes; rapping off single-pitch routes instead of just being lowered; thinking aid climbing is either valid or fun; going fully a muerte before getting the second bolt clipped; and so on.

Beta is everywhere in climbing. It’s absolutely inescapable, the proverbial great squid wrapped around the face of our sport. And as a veritable living organism, beta is actually quite fascinating. I can’t think of a more vibrant example of an oral history being shared and passed down through a community of people than beta among climbers. I know beta like I know lyrics to a favorite song.

Consider how many routes, moves and sequences you can recite with crystal clarity, on command, to anyone—even those who speak different languages! Through our signature gestures and pantomimes, and words like “shark’s tooth,” “bread loaf,” “pistol grip,” and “bass mouth,” climbers possess this amazing ability to communicate and share knowledge with each other. Our routes are not just pieces of rock with a grade; they’re totem poles that tell stories of all who’ve trod before us.

It’s hard to navigate that treacherous transformation from beta receiver to beta giver without stumbling into the usual blunders.

Not surprisingly, considering that beta is such a powerful, ubiquitous tool, our relationship to it is fraught with egoism. There are people with whom you are happy to share or receive beta; and others whom you’d sooner see come down with syphilis than tell them about the “thumbercling” (or worse: listen to them tell you about it, as if they were the first people ever to!).

Not surprisingly, considering that beta is such a powerful, ubiquitous tool, our relationship to it is fraught with egoism. There are people with whom you are happy to share or receive beta; and others whom you’d sooner see come down with syphilis than tell them about the “thumbercling” (or worse: listen to them tell you about it, as if they were the first people ever to!).

Everyone needs beta at some point, and being able to give and receive it without condescension is healthy. However, at what point does beta begin to detract from the experience?

To me, there’s nothing more obnoxious than really strong climbers who don’t want to spend the time to figure out how to climb a route, and just want to be told what to do so that they can get the send before everyone else. These “beta bitches,” as I call them, don’t seem to appreciate the degree to which their successes rely on the work, effort and creativity of other climbers. You never hear this side of a hard ascent reported in the media, even though the number of tries is mentioned, and that may or may not be an impressive stat based on how much information about the route (especially a cryptic route) was provided to the climber.

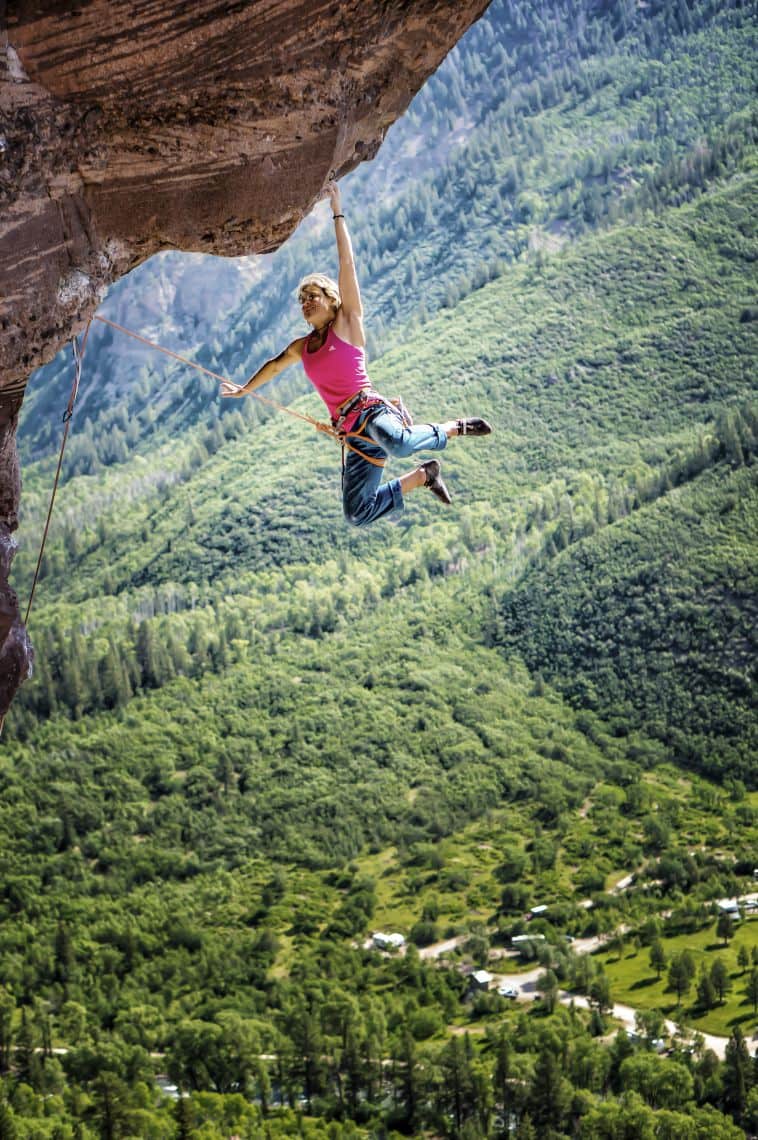

You see this a lot in Rifle, which is one of the more beta-intensive places to climb. Strong rope guns who are passing through don’t want to flail or put in their dues to learn the style of movement here; so they soak up all the beta they can, which is sometimes information that literally equates to 20-plus years of other climbers’ efforts and refinements. They get the redpoint second try and record as many points as they can get away with on their 8a.nu scorecards. (Strangely, these same climbers think that these routes, many of which were first climbed without kneepads, are sandbagged despite the fact that every single hold and sequence is handed to them on a platter. There’s no question that the 1,000th ascent should technically be easier than the first ascent, though grading trends seem to suggest otherwise, likely because people nowadays think they’re stronger than they actually are.)

Mobbing up beta just to get a quick tick is an approach that reduces rock climbs to mere prizes to be won, as opposed to the powerful learning experiences that they so obviously can be.

It’s easy to use beta as a means to power, a way to assert your superiority over someone else. On the other side, it’s ungrateful not to recognize beta as a gift. I think it’s hard to find a balance and enact it in real life, but I recently read a passage in one of my Taoist books that seems apropos to the issue.

“If you can help someone do something, then you should do so without any hesitation or expectation of reward. If there is something that you need to learn and your companion can show it to you, then you should accept it in humility. No one ‘owns’ knowledge. It should be freely shared.”

Very nice! Reminds me of an Econ professor I had. “Knowledge is the only good that actually increases every time it is shared.”