The Guinness Book of World Records has weighed in on an important piece of climbing history: Reinhold Messner is not the first person to climb all 14 8,000-meter peaks without oxygen, they say. Now, many climbers, myself included, are treating this announcement as if it changes absolutely nothing while rolling our eyes so far into the backs of our heads that we are winking at our own asses.

Do these fools really think that we’re just going to give Messner’s keys to the castle over to Ed Viesturs? After all, this is the guy who, in his cameo in Vertical Limit, was too much of a wuss to strap volatile Pakistani-grade nitro onto his body and climb K2 in order to save his fellow mountaineers! Now, what? … We’re just supposed to accept that he’s the new guy?! The guy to do all the 8,000ers first?! I’d rather suck frostbitten toes!

And to Ed Viesturs’s great credit, he agrees!

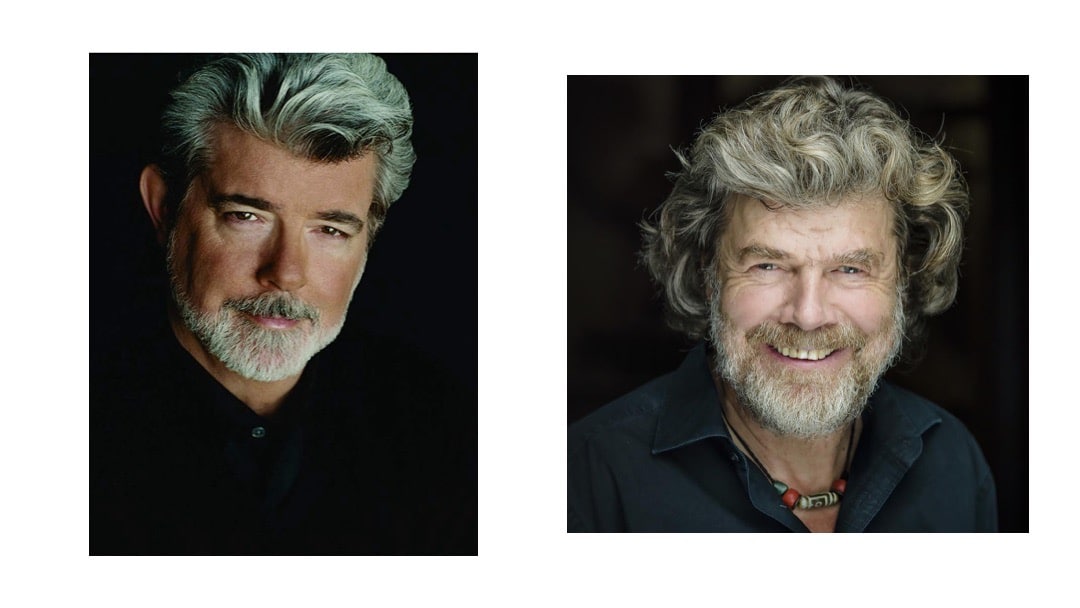

The last time the Guinness Book of World Records was relevant to me was in fourth grade, when my friend brought an actual Guinness Book into school. The picture book edition for kids was filled with equal parts fun facts and oddball freaks, like the person with the longest toenails or the heaviest beard or the stretchiest skin. We looked through that book and laughed at this strange carnival of humanity. Does anyone care if Reinhold Messner gets to be a part of this so-called “book” for any reason other than “world record for most looking like George Lucas”?

Unfortunately, Messner is doing himself no favors by trying to act like he doesn’t care about this. “Records don’t matter,” says the guy who is living in not one but two different castles based on his own records mattering. The record matters quite a bit, actually. Messner’s message is a mess. I wish that instead of trying to play it cool with one low-key Instagram post after another, reminding everyone on a daily basis about just how little he cares about records, Messner would sound the trumpets and come out onto the balcony of his stone turret, and offer a forthright defense of his incredible climbing record to the frothing peasantry. And with our low IQs and poor impulse control, you know we’d eat it right up.

In case you haven’t heard the scuttlebutt, German map nerd and bonafide non-climber Eberhard Jurgalski has been working on a project over the past decade using the latest satellite imagery and GPS technology to pinpoint the true summits of the world’s biggest mountains. With this info, he has been meticulously revisiting mountaineering’s record, comparing summit accounts and photography against his findings. From this, he came to a striking conclusion that suggested, at least at one point a couple years ago, that it was theoretically possible that no one had actually climbed all 14 big ones, assuming that “climbed” means physically standing on top of the exact highest point on the mountain.

John Branch, as per usual, wrote an excellent piece titled “What is a Summit” in 2021 for the New York Times that explored just how complicated this seemingly simple question can get, especially in light of Jurgalski’s research.

Since then Jurgalski’s inquiry has continued, and as of this August, he released his final report, which revises the climbing record thusly: Viesturs, in 2005—not Messner, in 1986—is actually the first person to climb all 14 8,000-meter peaks to their true summits without oxygen. The basis for this revision is Messner’s 1985 ascent of Annapurna, a mountain whose summit is one long ridge with as many as eight distinct summit-like points. Based on Messner’s account of being able to see base camp from the summit, Jurgalski posits that Messner wasn’t actually on the true summit as identified in his own research, but rather on one of the ridge’s false summits, a mere 5 meters in absolute elevation below the true one.

In the afore-linked Times article, Messner says that it was hard to see due to poor visibility. Being on a 3-kilometer-long ridge, he admits it was hard to judge where the summit was and so he made his best effort. He’s also stated, in an interview with La Repubblica, that Jurgalski is confused and also adds in that “he is someone in search of attention without having the slightest competence.” Also possible: mountain features, such as ridges, that are made of snow and ice are prone to changing over the years and so Annapurna’s ridge circa 2020 may be slightly different than its 1985 self.

Also interesting: Jurgalski is further suggesting that no woman has climbed the Full 14 without oxygen. And as for records with oxygen—which, let’s be honest, who cares—they’ve changed hands: Nims Purja, in 2021, is assigned an honor that originally belonged to Jerzy Kukuczka, in 1987, for the men. And for the ladies, Dong Hong-Juan, in 2023, takes it from Edurne Pasaban, in 2010, for the women.

I find questions about how historical revisions affect our understand of climbing history to be really vexing, as I’ve written about before. Historical revisionism is a valid, if fraught component of history and research that academics ought to pursue in good faith. At its best, historical revisionism illuminates and complicates history in a way that allows us to better understand it in all of its full and messy truth. At worst, it can be a way for politically motivated ideologues to validate their preconceived notions and lend false credibility to their worldviews and moral preferences.

Before tearing Jurgalski a new one, I think it’s worth mentioning that I agree with the thrust of his work. I view what he has been up to as an academically heroic effort, which has given us vital knowledge about important places climbers care about. I also tend to agree with the principle that you can’t say you’ve climbed a mountain unless you’ve stood on its summit and that this is all but a binary question. That said, I do believe the concept of “summit” can be treated charitably—someone who is chilling near the top but doesn’t actually place their boots over the precise X-marks-the-spot apex of the mountain has successfully climbed the mountain in a way that’s clearly much different from the person who is half an oxygen canister away from death and being dragged by a Sherpa to collapse in a heap on the same high point.

I also believe in the premise that there is an objective reality to mountains that allows us to say, quite definitively, what is its highest point. Postmodernist climbers have tried over the years to come up with different rationales that redefine success in individualistic, relative terms. That kind of broken-brain analysis may have a place if you’re writing jerk-off poetry for the Alpinist, but doesn’t offer any coherent way to think climbing and its record. More importantly, the postmodernist approach leaves open too many loopholes for self-promoting hacks to create the relativistic conditions by which their mid-tier achievements suddenly appear noteworthy, which they inevitably parlay into business and professional opportunities.

It’s important to mention that, on these points, Messner agrees! Over the years he has stated his opinion that you can only say you’ve climbed a mountain when you’ve reached its top, not when you decide your “personal journey” is complete; not when you’re close enough but too tired to continue any further. He approached all of his ascents in this way and only claimed success when he had achieved summits by these standards in good faith. (And since I took a snarky pot shot at Viesturs for no real reason earlier, it’s worth mentioning that he also has earned this integrity. After the Himalayan historian Liz Hawley told him that the central summit of Shishapangma “didn’t count,” he went back and climbed the whole damn mountain again to reach the main one.)

One could imagine an alternate world in which Jurgaliski simply released his research into the wild and let the climbing world decide what to do with it. One could imagine his findings leading to an interesting discourse about the importance of reaching the true geographical high points of these peaks. This would naturally lead into climbers offering some valid critiques about the way that many of today’s guided “climbers”—aka the oxygen-sucking Jumar jockeys riding the Sherpa-installed fixed ropes—are being told by their guides that they’re succeeding when arguably they’re not. Manaslu, perhaps, is the most notable example of this kind of “summit slippage,” in which the commercial guiding industry has agreed to dupe its clientele into believing that the flat spot quite obviously below the true summit—and notably beneath some rather hard, technical climbing—is considered totally valid.

Instead, Jurgalski, perhaps motivated by a desire to make a big splash and see his didactic efforts validated, consciously went after the most conspicuous mountaineering record via Guinness. The fact that Jurgalski actively petitioned Guinness—while, rumor has it, also being on their payroll—to try to revise one of climbing history’s most important touchstones doesn’t really sit well with me.

Perhaps it’s because Jurgalski isn’t a climber, or perhaps it’s simply because he has some kind of grudge against Messner after Messner, being the abrasive and at times egotistical Boomer the he is, attacked Jurgalski in the press over the past few years … but my impression of Jurgalski choosing to go out of his way to try to revise the climbing record in this fashion is that he is showing his profound incomprehension of what mountaineering is fundamentally about. I mean, that incomprehension begins right with thinking that any climbers would ever consider the Guinness Book as having any dominion whatsoever over the climbing record!

I get the instinct to be pedantic about having some basic rules about what counts in the mountains, but context so clearly and vitally matters in terms of what we choose to celebrate. Imagine being at the World Series, and seeing a Grand Slam in the ninth inning, and spending the next 10 years of your life reviewing footage to make sure that the batter’s foot touched every single base while rounding the field. That exercise might uncover something interesting, but it would fundamentally say nothing important about what made that game, that moment in time, so extraordinary. It would simply change nothing.

Look, I concede that climbing needs its share of Jurgalskis. There are valid reasons to be pedantic about summits and that’s because most people aren’t Messner—but some of them will cynically try to be. They don’t have the vision, audacity, and sheer mania required to do something so drastically groundbreaking and in impeccable style when no one was even asking for that. But they can craft a clever narrative that places themselves on equal footing. It’s important to reserve the right to be the pedantic critic in these scenarios, when people try to claim success for being the first this or that to do blah-blah-blah. Without Jurgalski, we might not have recognized that of the 160+ people who claimed a summit of Manaslu in 2016, only 15 of them actually stood on the real top.

Jurgalski’s research has the power to be a useful looking glass through which we see mountaineering in a new way. But that’s not what is happening through his sad and ultimately futile attempt to throw shade at Messner. I see this attempt at revisionism as obscuring more than it reveals.

The premise that what Messner did in 1985 on Annapurna somehow doesn’t count flattens all that’s great about mountaineering down to a single point—important, yet utterly arbitrary and absurd. The paradox of the summit mattering and not mattering at the same time is precisely what elevates mountaineering beyond sport. Beyond games like the chutes and ladders and fixed ropes that stand in as a facsimile for true mountaineering in places like Everest. To buy into this new version of climbing history is to turn peaks into tick boxes. It is to deny all climbers a reason to elevate themselves to the true challenge of the mountain, as Messner did with each of those 14 ascents, so that they too might experience the depth and mystery of climbing’s greatest paradox for themselves.

Kind of a disturbing conversation. A summit is a good goal to have in mountaineering. I think the suffering along the way is what transforms the person rather than the stunning vistas or the moment of standing on X marks the spot. It’s a great and worthy game.

Sad to see Kukuzca lose standing. Messner may have had impeccable style on the trade routes but Kukuzca was right behind him repeating the same peaks without oxygen, almost all of them via new routes or first winter ascents and many in alpine style. Kukuzca only used oxygen on Everest, on a new route.

He had none of the means Messner had and couldn’t access modern equipment. His club had to make their own winter gear and bribe officials for rations of spam to fuel their ascents.

There is only the one summit, and you made it or not. Alas, thus does logic cruelly strangle us all.

BUT:

No mountain is categorically stable in time.

A climber can mistake a false summit for the real.

Satellite imagery and GPS technology are useful but not foolproof.

The climber leaves his heart on the mountain. Mr. Jurgalski does not, must always be at fault in the intensely moral sphere of mountain climbing.