You’ve heard of farm to table, but all across the country, a new artisanal movement is taking place among rock climbers. It’s called gym to crag, and it’s an educational initiative to help people learn what’s really involved with climbing outside.

Many climbers are introduced to climbing in a gym. Climbing gyms are excellent places to learn proper belay technique and hone the fundamentals of free climbing. The walls of most gyms are also equipped with fixed quickdraws to practice leading.

Climbing outside is nothing like climbing in a gym, however,

Sport climbing areas, as opposed to trad crags, are as close to an indoor gym arena as you get outdoors, though their differences are vast when it comes to the super important stuff like safety, and the other important stuff like etiquette, good behavior, and leaving no trace.

Climbing Outside is Dangerous

The first and last thing you need to know about climbing outside is that climbing is dangerous. This can’t be stated enough.

Basic Crag Etiquette

Just like in the gym, routes should be shared among the climbers who are there. Unlike in the gym, however, climbing outside means that you are responsible for setting up your own gear, including top-ropes, placing quickdraws, etc.

Some crag are small, and just because you got there first, doesn’t mean that you now get to own a route all day. If you want to leave a top-rope up on some route, that’s potentially fine, but be considerate to letting other people have a turn if they want it.

Another thing to consider is not blaring music if other people are around. Some people might not want to be at a Diplo concert if they’re just trying to do some pitches.

Dogs are usually welcome at crags, but don’t let them just around greeting every single person at the area. If you’re doing a multi-pitch, don’t bring your dog and leave the animal at the base of a wall. This is super irresponsible and stressful for dogs.

Don’t Chip Rock, Deface Artifacts, or Place Bolts

If you’re honestly a gym climber, and you’ve heard about this cool thing called “doing first ascents,” please stop what you’re doing and immediately hop up and down on one foot like you’re trying to get water out of your ear until this idea leaves your head.

We’ve seen a number of stories recently that I wouldn’t have believed could be true several years ago, from climbers bolting 5.3s over hieroglyphs, to rank noobs slamming studs into the wall on a first ascent. Most people should not be doing first ascents, or placing bolts, or even re-placing bolts. Leave this to experts, please. I understand that this feels like “gate-keeping” and is potentially problematic, but it’s true and the alternative is worse. Elitism has a place here.

Don’t chip rock, either, especially on routes and boulders that have already been established. This includes using a wire brush to “clean” holds.

Practice Leave No Trace

It seems obvious to me and many people that you shouldn’t throw garbage where it doesn’t belong, but apparently even climbers aren’t above this kind of behavior. Obviously, the goal is to leave crags cleaner than when you found them. Stay on trails, don’t leave trash, and properly dispose of your own waste.

Leave No Trace doesn’t just mean not leaving your tape wads at the base of the wall; it also means, for example, not have rave parties at crags or keg parties on summits.

Understanding Climbing Gear Outside

Gym climbers who venture outdoors must learn how to become completely self-reliant and responsible for their actions. This begins with knowing the basics of how to belay a leader, and extends to knowing how to evaluate the integrity of your own gear as well as any gear that’s fixed on the wall: whether that’s bolts, permadraws, or just manky old slings. Also important is knowing how to avoid loose rock, and respond appropriately to bad weather, especially lightening. Be aware of these crucial points:

Don’t assume any fixed gear you find outdoors is reliable. In a gym, setters and gym owners make sure that their ropes are in top condition, that bolts are properly tightened, and topropes are safely strung. Outdoor crags have no one checking to make sure anything is safe.

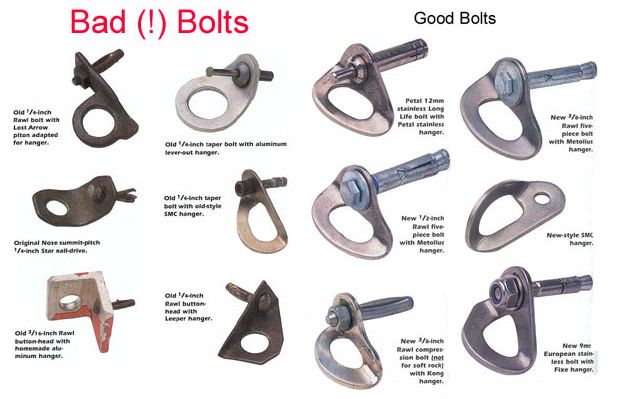

Bad bolts may be a legitimate concern in some places. However, at most crags, especially on popular routes, older bolts have been replaced with honker ½-inch five-piece expansion bolts or glue-ins, which are extremely solid. Look at the bolt’s nut: Is it securely threaded on the bolt, or is it about to unscrew itself? Is the hanger loose? Is the bolt heavily rusted? (A little rust can actually be perfectly safe). Is there a gap between the bolt/hanger and the rock itself? These things may indicate a dubious bolt.

A more common concern will be the integrity of those fixed quickdraws that have been hanging on routes, sometimes for years. Be wary of faded nylon quickdraws, and always check the basket of every carabiner you clip to see if it is sharp. Never clip a sharp carabiner—replace it with your own new one.

Outdoor climbing areas are dangerous. Rocks fall, people drop gear and bad weather moves in. Wear a helmet, even for belaying. Dress properly, and always be prepared for the cold and rain.

Route vs. rope length.

Lowering a climber off the end of the rope is never a concern in the gym, but it is outside. A 60-meter (200-foot) rope will get you up and down 75 percent of all single-pitch climbs in the U.S., but don’t assume that it will. Consult guidebooks and other climbers about a route’s length, and make sure that you will be able to get all the way down on your rope. If a route is 30 meters long, you need at least a 60-meter rope!

And whatever you do, always tie a knot in the end of the rope.

“Strong” Doesn’t Always Matter Here

Gym climbing is not sport climbing. With the plethora of training apparatuses like tread walls, system boards, hang boards, and campus boards, you can get ridiculously strong in a climbing gym. However, that strength doesn’t always transfer directly to sport climbing. Standing on plastic footholds and following a taped route on a wooden wall will not fully prepare you for climbing on real rock. Here’s a few reasons why:

• Real rock can be sharp and painful. Your skin may be callused, but if it’s only accustomed to grabbing plastic, friendly holds, you may find that your skin gives out before your muscles do. If this happens, make sure to take care of your skin that night by rubbing vitamin E oil into your tips and moisturizing. Skin with more moisture has more water in it, which makes it stronger. Dry, cracked skin tears easier. Lightly file down calluses and any raised tissue that could catch on a sharp nubbin and tear off.

• People set gym routes; rock is natural. This is obvious, but the point is that rock climbs demand moves that you may have never seen or practiced before. Real rock climbs are more three-dimensional than gym routes. Prepare to be frustrated, stymied, and more pumped than you think you should be.

• Sport climbing may feel scarier. People are instinctually afraid of anything unfamiliar. If you’ve only climbed in the gym, you might find climbing outside to be a bit headier. Don’t worry about it; this is natural. Relax, breath and drop the tension from your shoulders. Take comfort in knowing that the more you do it, the easier it will be.

Not All Routes Are Safe!

Not all route developers know what they are doing, and I have definitely climbed my fair share of routes that were just unsafe. Sometimes, loose rock hasn’t been properly cleaned, or the route takes you up a sketchy loose flake that, while it may be covered in chalk, looks like it could pull out at any moment. Threats such as this one could potentially injure your belayer or cut your rope.

Sometimes developers have mistakenly placed bolts in such a way that it will cause your rope to run over/around a sharp corner/edge—if you fall, there’s a chance your rope come taut on the sharp rock and cut. Though the route developer may be to blame, it’s still your responsibility to recognize dangerous situations and avoid them.

Bail off any climb you think is dangerous—there are plenty of good, safe and enjoyable routes out there.

Hi Andrew, what route is that lead photo from? Thanks!

Eye of the Tiger, 8a, Grampians, Australia

Good post! I’m shocked how many people I know say they climb, but then when I invite them climbing say, “Where? Outdoors? Oh, no thanks!” My attempts to explain that’s like spending your life in a gym on a treadmill and never going for a run only get me quizzical looks most of the time.