“Projecting” is the process of working toward “redpointing” a rock climb. This process is the heart and soul of sport climbing. It’s when you’ll feel extreme highs and surges of motivation, and also go through periods of deep frustration. It’s also when you build a deep bond with that rock climb in such a way that it will forever become a part of your life as a climber. This article will give you basic understanding of the process—and it very much is a process—for redpointing sport climbs.

Hangdogging, beta rehearsal, pre-placing gear and tick marks, ruthlessly wiring cruxes—these are some of the classic tactics that climbers employ to redpoint a route at their physical and mental limit.

Redpoint is a term that dates back to the early 1970s in Frankenjura, Germany’s largest climbing area. Here, the local climber Kurt Albert drew a small circle at the base of a climb that had not yet been completed. When the route was finally sent—that is, free climbed from the bottom to the top without falls—Albert filled the circle with red paint. The German word rotpunkt (rot = red, punkt = point) birthed the term redpoint.

A redpoint differs from an onsight or flash in that a climber takes more than one attempt to free climb a route. Originally, one qualifier of a redpoint ascent had the climber placing draws or gear as they ascended—climbing a route with pre-placed draws or gear was disparagingly called a “pinkpoint.” This distinction, however, is all but obsolete and now any sport climber with nothing to prove uses “redpoint” to describe a successful ascent of a route, pre-placed gear or not.

The Redpoint Temperament

Projecting doesn’t come naturally to everyone. Working on a route for days, weeks or sometimes years takes a certain type of determined, if stubborn, personality. Do you like adversity? What about monotonous adversity? This is sort of what it is like to go up on a project and climb on the same old rock grips, day after day, only to fall at the same spot, again and again.

For some, the projecting mentality comes naturally—these people often grew up doing such things as preparing for piano recitals or gymnastic routines or anything where it is normal to ruthlessly train for the one day when you supposedly perform your best.

I was not one of these people. It took me about two years to appreciate the redpoint style of climbing. I hated falling on moves that other people found easy. I hated projecting other climbers’ warm-ups (I still do). I hated the tedium of climbing on the same route every day. It felt like work when climbing is supposed to be anything but.

More than anything, I hated the tremendous pressure I placed on myself to redpoint. Once I knew it was possible to succeed, I felt an anxious dagger carving me up inside, a feeling absent when climbing easier routes onsight. I felt obligated to redpoint, like it was something I had to do. I especially hated it when this anxiety caused me to tense up and fall again.

But I kept at it because I believed in the power of this one idea: Projecting makes you a better a climber. It really does. Not only that, but the process of working a route can reveal certain strengths and weaknesses that you don’t see elsewhere. Eventually, this becomes the point of the rather pointless exercise called sport climbing. Stick with it, even when it sucks, and take comfort in knowing that climbing becomes difficult for everyone at some level. That’s what we’re here for. There’s nothing to be learned from the easy path. The point is finding your limit and then pushing it. If working a route feels like work, that’s because it is. But nobody ever died from a little hard work, so let’s get into the tactics that will help you combat the colossal forces impending the long journey to a successful redpoint.

Use your time on a route to always learn something new

Always learn something new each time up the route, and you will make progress with every attempt. Ingrain this advice into your projecting mentality, and you will not only find yourself doing harder routes in fewer tries, but you will be a smarter climber than most.

If routes were books, climbers tend to skim over them. The righteous path is to study, then practice and finally master the information at hand. To send a hard route, you have to learn it. You want to be able to visualize every single hold within a few trips up the route. Eventually, you’ll know these holds better than your family, and you’ll love/hate them just the same.

Find a slightly better hand position, discover a new rest, or use a higher foothold (even if it’s worse) to do a reachy crux. Constantly re-evaluate your strategy and don’t hesitate to change it. Maybe you rest longer at one spot, or maybe you don’t rest at all. Experiment. Don’t climb with blinders on. The name of the game is to find the absolute most efficient way to move upward.

Learning on a route isn’t exclusive to the free-climbing beta either. You could spend your projecting session learning how to clip a hard-to-clip quickdraw better—finding a more efficient body position that works better for you. That might mean learning to cross-clip instead of matching on a handhold.

You could learn that a fall going to the anchors is totally safe. With that new knowledge, next time you get up into the runout zone, you’ll be more likely to stay relaxed, climb efficiently and go for it.

The great upshot of this most general advice is that learning gives you purpose even on days when you’re not feeling strong. You can always learn something new, even on off days. If you feel weak, like there’s no chance of redpointing that day—don’t worry. Go up on your project anyway. Use the opportunity to hang on every bolt as a chance to learn your project better.

People who think that they’ve learned everything are always ignorant and often old. Avoid this mentality. The point isn’t necessarily to be climbing better with each burn, but to be mindful of the learning process, which shouldn’t end for any route until it has been redpointed.

Break it down

Difficult routes always seem intimidating and unfathomable at first, like the famous 72 oz steak challenge at the Big Texan restaurant, in Amarillo, Texas. Your only hope is to cut it up and take one bite at a time. If Texans can take down half a cow, you can send 5.12, 5.13 or even 5.14. Why not?

First, break the route down mentally—logically and elegantly. When you look at your project and no longer see a 100-foot nightmare, but rather a manageable stack of three to five sections (a good range to shoot for), you will have created the building blocks of the strategy you’ll use to send the route.

All climbs can be deconstructed. Often, routes break down by physical attributes: where the cruxes and rests are. For example, let’s say a 100-foot route has a pumpy strart leading to a definitive crux followed by a good rest and capped by a “redpoint crux” before the anchor. In this example, there are four to five distinct sections: the pumpy start, the crux, the rest, and then the final run (which can be broken down into two sections if the redpoint crux is problematic). Regard each section as its own mini-route, and work on sending each section independently.

Some routes, however, are sustained the whole way, and cutting them down becomes trickier. An obvious divider is the number of bolts. If there are five bolts, then there are only five sections you have to do. Use creativity to help yourself digest each piece. Tell yourself, “If I can do five boulder problems in a row in the gym, I can do this route.”

A bad way to break a route down is to divide it by where you fall. Where you fall will change from day to day, so it’s not useful for scientifically deconstructing the route. Also, breaking the route down by where you fall is a typical mental error that creates a self-fulfilling prophecy. Looking up and seeing a fall spot places a negative idea in your head that need not be there at all. The rock presents enough challenges and there is no need to add another one if it only exists in your head.

Early Attempts

On initial tries, you will likely be hanging on every draw. Also, expect the first time up a new project to possibly end your day, and definitely crush you like a pumped little bug. That’s normal so don’t be blue. Stay positive, and use the opportunity to learn. Experiment with beta, extend draws for easier clipping, place thumbprint-sized tick marks where needed, and memorize subtleties of holds and body positions. I always use my first time up a project to try to just dial in the draw configurations and make sure I know where I’m going to clip from.

Don’t be afraid to grab quickdraws on your first few times up a route while you’re working it. Who cares? You’re hanging on them anyway at this point, no need to be proud. However, if you’re grabbing draws on your actual redpoint burns, then that’s a bad habit and you’ll need to start pushing yourself to learn to just take the whipper.

Skip it or clip it?

If one clip is giving you trouble, consider skipping it. The crux of a sport climb should be the free climbing, not clipping the rope to a quickdraw.

Evaluating the safety of skipping a clip demands experience. Usually, any bolt high up an overhanging route is OK to skip because the worst that can happen is you’ll fall further through the air. As long as don’t hit anything, a fall through the air—even a big one—is safe. Skipping a clip that’s close to the ground is obviously more dangerous because you run the risk of decking. Take precaution and err on the side of safety.

If you decide to skip a clip, consider extending the next quickdraw so you can clip it sooner. Or consider using a shorter quickdraw on the bolt below the skipped clip in order to shorten any fall you may take.

When You’re In Direct

When you fall or take, clip yourself in direct to your highest bolt using your hangdogging quickdraw. Once you are safely hanging from the bolt, the belayer pays out a length of slack, and enjoys a free moment to move, stretch the neck, become re-established at the belay and relax in general. Likewise, use this time to compose yourself, relax and breathe. Review what you have just climbed. Look at the holds. Learn them.

They say that it takes most people three times to learn anything. Keep that in mind. Experiment. Try something ridiculous—maybe a double dyno would be less pumpy! You have nothing to lose. Find the most efficient way to climb from bolt to bolt.

Ask yourself, “Why did I just fall?” Was it from being pumped? If so, were you grabbing the holds too tightly? Or were you out of balance? If that was the case, study the holds and visualize a different body position that may work better.

Now is also a good time to place tickmarks on hard-to-see hand- or footholds. Take a chalk pebble and make a thumbprint-sized mark above, to the side, or below, the hold. Brush chalk off of handholds too. Again, it goes back to that point of always making sure you’re learning something new that will help you climb more efficiently.

When you feel rested, call down “Take!” to your belayer. Once the belayer has your weight, unclip the dogging draw and place it back on your gear loop.

Always lower down two or three moves and get back on the wall there. So many people make the mistake of just pulling onto their highpoint, not realizing that they actually are skipping one of the moves that the didn’t do. You always want to practice climbing into the sequence.

Making Links

Climbers often “project” a route by climbing until they fall, resting for a totally random bit of time, trying again, getting a couple of holds higher, falling again and repeating. One day, they either reach the anchors or give up and admonish themselves for not having enough strength and endurance. This typical behavior, however, is sort of like banging your head on a wall to get into a new room instead of using the door.

After you’ve mentally broken a route down into sections, it’s time to start linking them together. Understanding how to make links is at the core of redpointing. The strategy you use to make links will not only be different with every route, but the process will become more innate and intelligent with experience.

Spend most of your time wiring the top half of the route. This important link is the one that climbers most often dismiss. They spend a disproportionate amount of time working out the crux, writing off the run to the anchors as something they’d never fall on. Problem is, they haven’t accounted for how pumped and tired they will be after doing the lower moves in succession—they reach the so-called easier climbing, forget where the holds are and, in the split second of hesitation, fall.

You will make it through the crux one day. When you do, you want to be sure you’ll send.

“Work” the Rests

Sport climbing is often more about learning how to rest than pulling hard moves. As you project your route, and work on making links, it’s important to learn the rests with the same dedication you learn the crux sequences.

If you’re lucky, your project has a rest where you can recharge your battery to 100 percent. If so, there’s no reason not to stay here until you do.

As you begin to push yourself on harder routes, the rests become more mental than physical reprieves. Even with straightforward rests, there are complexities that aren’t necessarily intuitive. Learning to shake out on a still-pumpy hold, for example: You may not fully recover, and in fact, the longer you stay there, the more fatigued you become.

In this situation, the goal isn’t to rest your forearms, but to slow your heart rate. Focusing on relaxing your heart rate—instead of your forearms—brings composure, and a clear head, to the very uncomfortable situation of hanging from the wall with pumped, aching forearms. With a clear head and a relaxed demeanor, you can climb through the fatigue, but you won’t make it more than two moves if you become frantic.

Other factors to consider are arranging the joints in your shoulder so that you are hanging from your skeleton. Use the friction between your skin and the rock to hold on. When you rest, you want to feel that should you let go of the rock any more, you’d fall.

Scan your body: where does it feel tense? As Lynn Hill counsels, “With a single exhalation, you can bring relaxation anywhere.” The absolute best training for this technique is yoga. I highly recommend taking an Iyengar yoga class once a week. It will teach you how to breathe, meditate and find repose in physically taxing poses, not to mention realign your structure and keep your joints healthy.

Highs and Lows

As you start giving your project serious burns, always strive to reach a new high point—that is, the highest point you can reach from the ground without falling. If you’re lucky, it’ll be the top!

If you do fall, however, work on gaining a new low point—that is, the lowest point on a route from which you start and can climb without falling to the anchors. This is also called working a route “top down.”

The basic idea behind top-down projecting is that you can send from the last bolt to the chains, then from the penultimate bolt, and so on. Eventually, you will link from the first bolt to the top, and if you can do that, you can send the route.

Top-down projecting is more theoretical than practical. No one follows this bolt-by-bolt succession with as much strictness, nor should they. It is wiser to act reasonably and try to overlap the route’s sections as it makes sense. Find a point in the middle of one previous section and overlap from there to the top of the subsequent section. Etc.

Joe Kinder says, “You must make links starting before the fall spot, even if it is three moves before. Gain confidence: it is the key to climbing hard!”

Top-down projecting is especially useful when a route is a sustained power-endurance pump fest. With these routes, redpointing from a succession of lower bolts makes more sense. You will not only dial in the most important part of the climb (the top), you will also gain the fitness needed to do it. Gaining fitness for sustained routes can take a long time, so don’t get discouraged. Top-down projecting is the best training there is for gaining the specific endurance needed to send the route.

The One Hang

Ah, the all-important One Hang! Nothing signifies that a climber is ready to send a project like the One Hang. Climbing your project with just one fall is to redpointing what wooing a crush is to the first kiss. You’ve bought flowers, gone on the requisite two dates, and met the parents. Conditions are prime for smooching, and you just need to make sure you don’t say anything stupid. And by that I mean you don’t fall at the top of the route.

However, don’t go patting yourself on the back just yet. A One Hang does not make, or even guarantee, a send. I know climbers who have climbed their project with a single hang over 20 times before finally giving up.

Still, the One Hang is the best indicator that a you are close to sending, and once you do achieve a One Hang, it’s time to go into battle mode: Get a good night’s sleep before your day out, eat and hydrate well and of course, properly warm up.

Troubleshooting the One Hang:

More rest:

You are likely not waiting long enough in between burns—I say that with assurance because almost no one does. On endurance projects, wait at least one hour, and as long as two hours, before trying the route again. Eat snacks and drink water. Consider ingesting small doses of caffeine. While resting, don’t make the common mistake of just sitting around. Research has proven that “active recovery” speeds the amount of time it takes to recharge your energy reserves. Essentially, doing light exercise speeds your body’s processing of the lactic acid in your forearms and back. After any taxing burn on a project, take an easy 20-minute hike. Even doing a lap on an easy climb will help you recover quicker (as long as the route is easy enough). Massage your forearms vigorously.

Breakthrough:

Perpetual one hangers have trained themselves to fall at the same spot. This mental block has caused more falls in sport climbing than cruxes have. As this is often a mental problem, making a breakthrough often requires changing your perception of the route somehow. Try climbing on an even harder route for a while and coming back to your project—maybe it won’t seem so bad.

Change something:

Another great trick for beating the one move trouble spot is to change something. Find new beta, even if it’s harder. Yes, that’s right. Do a different sequence. Break the mold. New beta will get you out of the rut you’re in. Your mind won’t know it’s supposed to make you fall because it will be thinking differently.

Warming up for the redpoint

“Not warming up properly is the biggest error I see climbers make,” says Jon Cardwell.

Indeed, properly warming up is the least understood and most beneficial thing climbers can do to help put them in a zone of top physical and mental performance.

Cardwell says he tries to do 100 moves before attempting to send an endurance route. Typically, routes that are 80 feet long have about 25 to 40 moves on them. Three to four routes of increasing difficulty is usually a good warm up. The final warm up should climax with a grade roughly one full number grade below your project. That is, if you are projecting a 5.12b, try doing a 5.10a first, then a 5.10d, and finally a 5.11b.

What are you warming up for? Is your project short and powerful? If so, try warming up on an easier, but still powerful route (as opposed to an endurance route). Another option is to climb a regular warm up using a different style: Instead of climbing slow and steady, make quick, powerful pulls between holds to awaken those fast-twitch muscles.

Especially consider what your project’s crimping is like. Single-pad holds require more warming up. If your project has some small edges, don’t just climb on jugs. Do something crimpy first.

Consider making one of your warm-ups an onsight. Trying a route that you’ve never done before awakens your mental muscle in a way that climbing the same old warm-ups does not.

The basic idea is to get pumped, but not be taxed. Your forearms want to be swollen, but not shot for the day. After warming up, rest 30 minutes at least before getting on your project. Stretch, drink water, relax and visualize yourself redpointing your project. Get psyched to try hard.

be lighter….

Andrew,

Fantastic article – it should help a lot of us get into the mood for projecting, thanks.

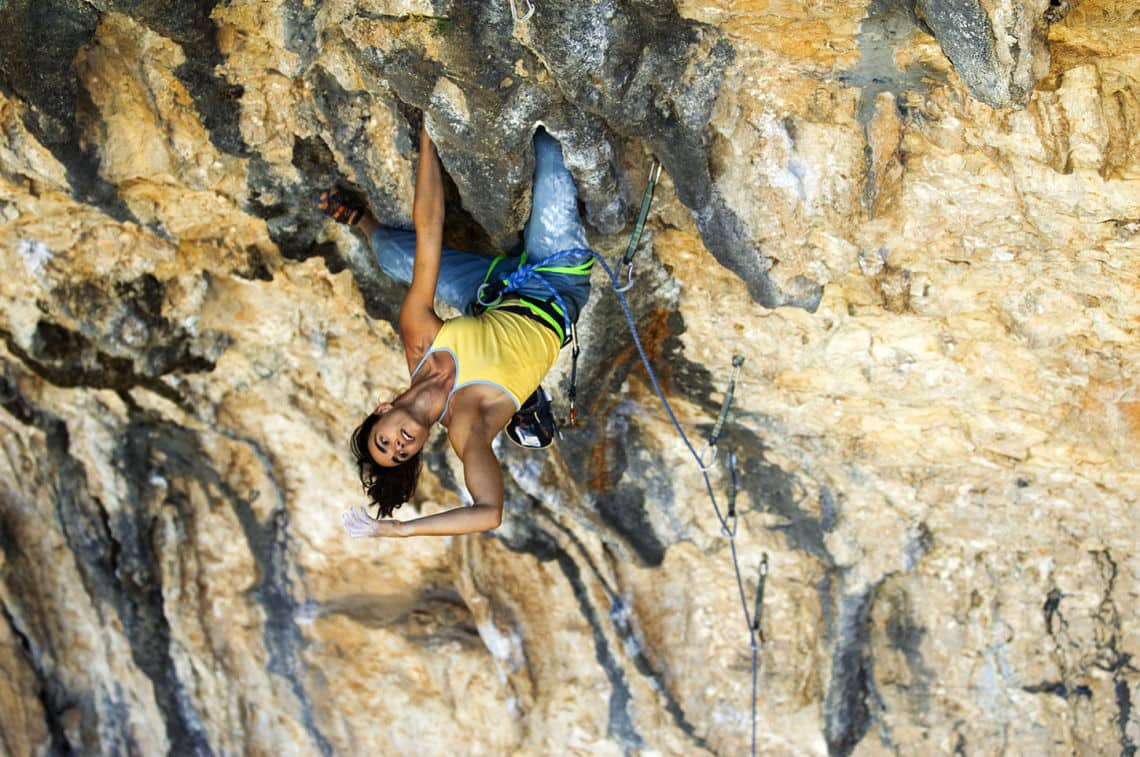

But is there any chance you could add more info on the pictures? That is, what is the route, and where is it? (e.g., what area in Utah has “the Hurricave”. Sure, we can google it, but that gets tedious for every picture…). For the first photo, we’re not even told the climber’s name.

The right temperament and highs and lows for sure! I’ve spent too many hours figuring out the best routes to take and it’s always worth it as long as you don’t let the downtime get to your head. Some awesome photos in this article Andrew, you should really get on Soul id and share some of this content with the community there. Check them out: https://soulid.me They have a section dedicated just to climbing too https://soulid.me/id/Climbing (Im on it like every day) Cheers!

This is such a good article… so little is written about this topic (though most climbers pick it up after spending years with other climbers projecting)

I think its not fair to say having replaced gear on a trad climb can have some sort of debate. See everything that occurred in the century crack. It is not even remotely a concern on sport climbing