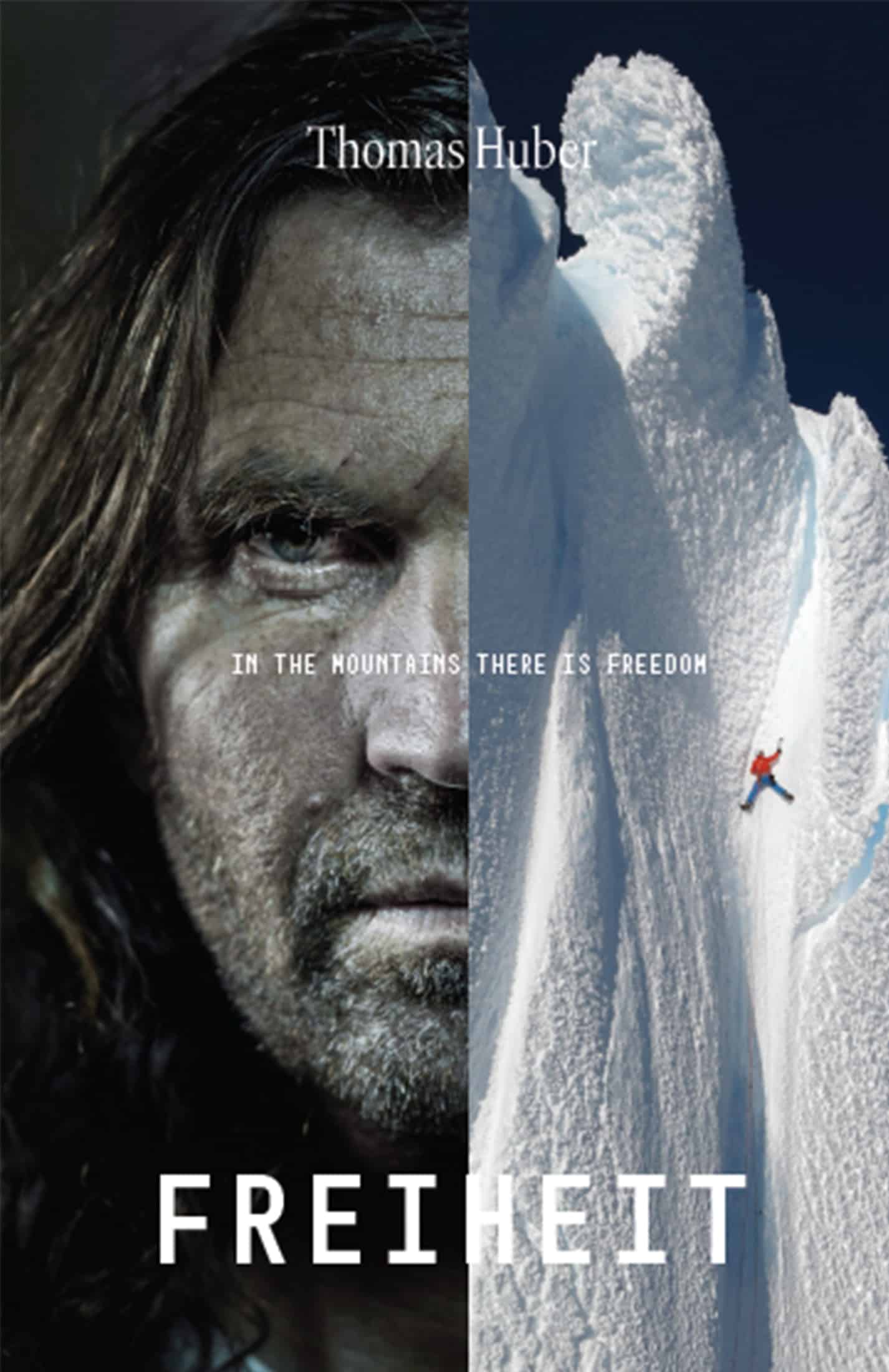

Ed Note: This is an excerpt from “Freiheit: In the Mountains, There is Freedom,” a new book by Thomas Huber, available in English from DiAngelo Publications. The Huber brothers Thomas and Alex—affectionately known as the Huberbaum—are easily two of the most prolific climbers of our lifetimes. This excerpt captures a moment in time, from 1991-94, when the Huberbaum were coming of age and beginning to make their first marks on the climbing scene. Alex, the stronger sport climber, established Om in 1992, proposing 9a, which would’ve made it one of the hardest routes in the world at the time, but never received the recognition it deserved until over a decade later when 16-year-old Adam Ondra made its first repeat.

Meanwhile, Thomas, more of an adventurous soul, found himself drawn to a stunning 11-pitch line on the Feuerhorn, which he bolted and ultimately sent, calling it The End of Silence. Together with Silbergeier in Rätikon and Des Kaisers neue Kleider on Wilder Kaiser it completes the so-called Alpine Trilogy, a trio of 5.14 alpine multi-pitch sport climbs that continue to inspire the imaginations of the world’s best climbers today.

To read more Day I Sent stories from top climbers, explore our full archive.

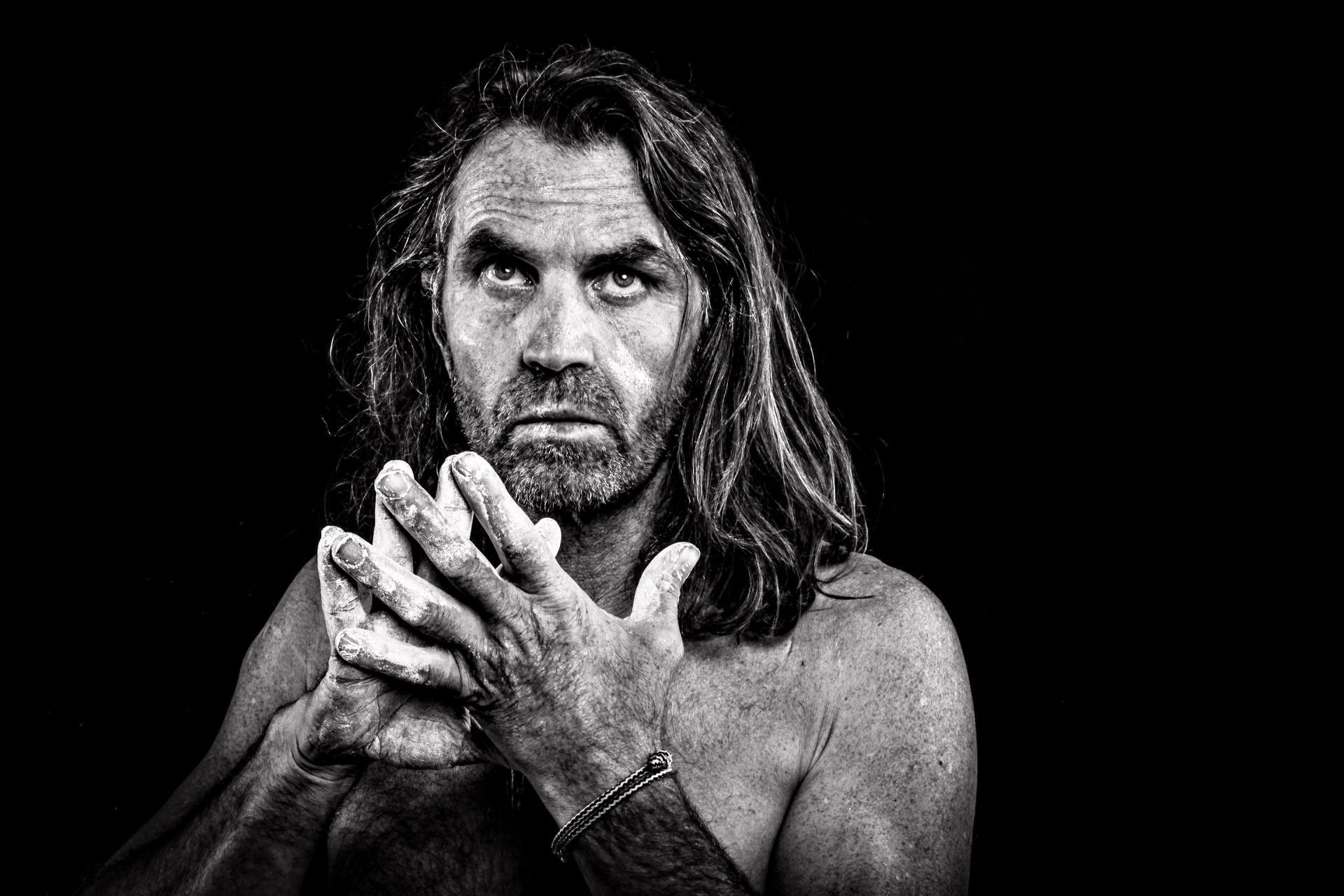

The time of my emancipation had finally arrived. I was still living at home, enjoying the benefits of a full fridge, but I already had different ideas. With a mohawk haircut and later with dreadlocks, I wanted to set myself apart from my parents in a provocative way. I began earning pocket money as a waiter at Nanu, a hip pub in Traunstein. My long-term goal was to work as a high school teacher, integrating climbing into school sports programs. There was no official climbing instructor for public schools in those days so I began training as a certified mountain guide, enrolled in a PE program at the Technical University of Munich, and began to build my foundation for a financially secure yet climbing-filled life.

Along with Alexander, Rudi Klausner from Berchtesgaden had become one of my closest friends. We both were in awe of nature and of life, and could spend hours conversing about climbing training and performance optimization.

Rudi was savvy, incredibly creative, and smart about improving his performance. With his individualized Klausner training plans, we brothers improved our climbing performance quickly; we were now climbing in the lower tenth grade and, with some good results in national competitions, had made it onto Germany’s national climbing team.

In addition, we had our first sponsor, Wolfi Müller, whom we knew from our time in Buoux. Thanks to his then hottest and coolest climbing clothing company, Gentic, we were now seen at the crag wearing white, sporting ibexes and Japanese lettering—and were even paid a little pocket money. Kitted out thusly, we clipped the chains on Vom Winde Verweht (IX, or 5.13a/b) on the Reiteralm’s north side and dispatched our first 8a’s (5.13b’s) in the Verdon Gorge. Nevertheless, we still had to acknowledge without any envy that in terms of climbing style and ability, we were still miles behind the French stars like the angelic Isabelle Patissier and the golden-locked Patrick Edlinger.

In late summer of 1988, I made the big move to Munich, into a two-room apartment in the Sendling district. Although it was a dark apartment—the high rise opposite blocked the sun—it had a unique flair. When both Alexander and I had signaled that we wanted to study in Munich, our father had bought this old apartment, which we lovingly renovated. Its 500 square feet comprised a small entry hall, a small bathroom, two rooms, and a kitchen. And because it was an old building, we had high ceilings—ten feet tall.

It didn’t take long for me to remodel my four walls to have a space to sleep, study, relax, work out—and climb. Six feet off the ground, I built a false ceiling over half the room. Up there was my sleeping level, and below that I framed in an overhanging home wall that folded down from above—a simple, unique design which allowed for a completely revolutionary training method. Rudi had the simple but ingenious idea of systematically integrating the finger-strength exercises from a hangboard or pull-up bar into climbing movements. I put his concept into practice by symmetrically fixing four rows of holds, each including crimps, pinches, sidepulls, slopers, and two-finger pockets. Below these rows of handholds, I bolted on small, symmetrically arranged rows of footholds. The world’s first system wall was ready, creating a training tool that would be copied globally and, shall we say, “revised” by intellectual-property pirates.

Alexander moved to Munich a year later, took up residency in the spare room, and began to pursue a physics degree. The Leipartstraße metamorphosed from a student flat to our very own training temple. During the day, we went to uni, and at night, we trained, the hard music of Monster Magnet, Motörhead, and Nirvana roaring out of the speakers in my room. Everything was coated with chalk, and the air was saturated with the smell of sweat. We were “on fire,” hungry for training, and banged out Rudi’s protocol on the system wall like fiends.

On the weekend, we drove back home. A quick hello and, typical for most spoiled, post-pubescent wannabes, we dropped off the laundry at Mom’s because Mom still did everything for us. Then, that same evening, we’d head to Nanu, where I’d kept a part-time job tending bar, while Alexander had also found work pulling pints. This went on until one in the morning. Afterward, we went to the Blue Velvet, a great rockʼn’roll club out in the sticks, where they played our kind of music. This went on until about 4:00 a.m. Then we would all get out to Karlstein in the late morning, where we climbed on our projects. Every aspect of our life was geared toward performance.

Our most memorable adventure during those days was perhaps climbing the route Scaramouche on the west pillar of the Hoher Göll, the high point of the Göli massif in Austria. The route climbed a gray, blank 650-foot slab with far-out-there climbing, including moves on monodoigts (one-finger pockets), frictionless slabs, and desperate dynos to crimps. We placed all the bolts on lead while hanging from fragile body-weight placements. And we did take some desperate whippers—one 50-foot flight left Alexander limping off the mountain with a sprained ankle. And yet, weeks later, we each climbed all the pitches free on lead. A dream line that deserved to be graded X (5.12+/5.13-). At that time, we were unaware that we’d established one of the most difficult alpine routes ever, and even today, a repeat counts for something. The Scaramouche became synonymous with adventure climbing. While all the bolt-spoiled climbers avoided it, there was certainly nothing ‘plaisir,’ as the Swiss would put it, about our route.

We finally traded in our run-down Italian car for trusted, sturdy Swedish steel. We embellished our new vehicle, a sky-blue Volvo station wagon, with a diabolic black buffalo head painted on the hood and adorned the rear-view mirror with eagle feathers. Motorhead’s “Rock ʼn’ Roll” would blare from the speakers when we brothers left university and steered our wagon east out of Munich toward the limestone cliffs of Schleier Wasserfall. Life was perfect in many ways. As Motorhead’s Lemmy Kilmister, my godfather of rock ʼn’ roll, put it, “. . . cause I’m in love with rock ʼn’ roll, satisfies my soul . . .” Never failing to add, “And don’t forget to rock ʼn’ roll!” to all his words of wisdom.

And he was right, there. There is much more to rock ʼn’ roll than the pure, raw music. It is an unconditional philosophy of life, wild, rebellious, anarchic, not letting anyone take away your right to freedom, going for your goals no holds barred, using your maximum power and all your energy. If you were to describe it in musical language, all the knobs would be on top, with the volume turned up to 10. No half measures, nothing half-baked, full throttle at any given moment, and no accountability for one’s actions, not even to one’s parents.

There is much more to rock ʼn’ roll than the pure, raw music. It is an unconditional philosophy of life, wild, rebellious, anarchic, not letting anyone take away your right to freedom, going for your goals no holds barred, using your maximum power and all your energy.

Of course, our parents still supported us almost 100 percent, but only on one condition: that we study! We fulfilled this condition without protest, except for our days off to go climbing. While Alexander disappeared into a world of mathematical and physical formulas that was alien to me, I did gymnastics, swam, and ran laps on the track; played soccer, basketball, and handball; and studied training theory, biomechanics, and pedagogy. These were contrasting academic pursuits, contrasting personalities, but an identical goal: to get a job that left plenty of time for climbing. Like our shiny blue Volvo, the future looked bright. We passed each semester’s exams while simultaneously pushing our climbing grades and even dabbling in competitive climbing.

Perhaps the most noteworthy competition was the German Climbing Championship in Munich. Alexander and I had got our training down to a T and were ready to go, maybe even for the podium. Expectations were high from the national coach and my private coach, Rudi. Alexander and I started late in the rotation because the best always came at the end, and by chance, it was my turn directly before my brother. Fully focused, I stood before the wall, tied in, chalked my hands, and placed my foot. I lifted off with the second foot, and exactly then, my first foot popped, and I was back where I had started. Off you go, untie, and please leave the stage. Next, please. I couldn’t believe it. Embarrassed, I walked off the stage, trying to hold my head high. Alexander was already on his way out. Sadly, he made the same error as I had—and that no other competitor did—and we finished last.

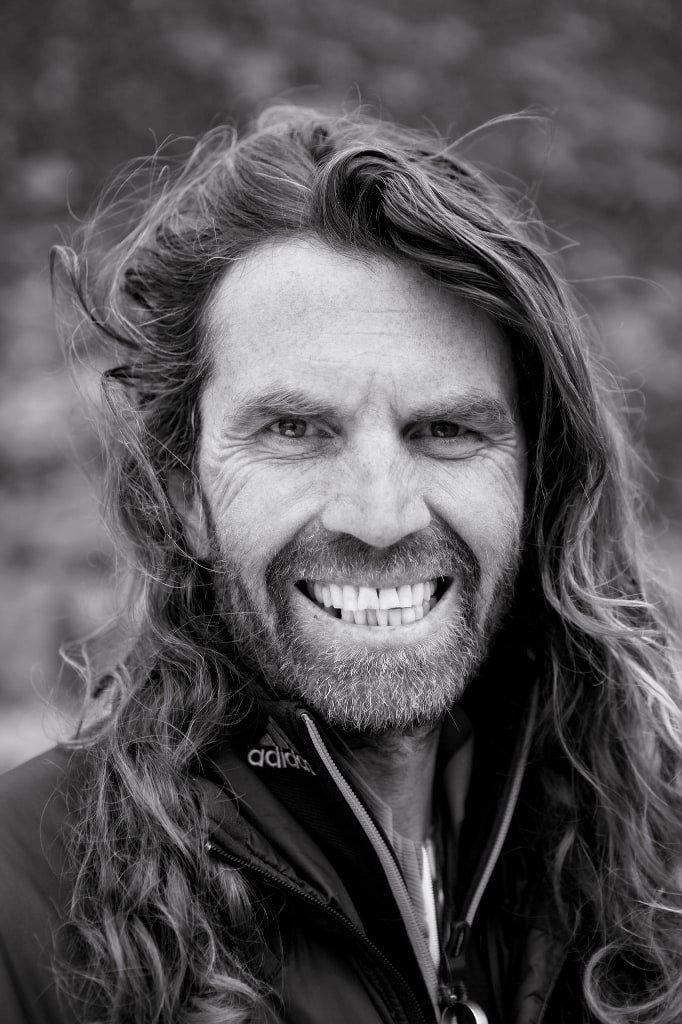

It seemed that the world of competition was not for us. Nevertheless, we were rewarded with a great time outdoors; on Karlstein, at the Reiteralpe, in the Dolomites, and throughout the South of France and Spain. We pushed each other and were usually the first to repeat each other’s projects. Being brothers that shared precisely the same passion, we were always compared to each other. Alexander was the “Little Huber” because he was shorter, while I was the “Big Huber.” Or Alexander was the “Smart Huber” because he was bright while I was the “Pretty Huber,” not because I was any better looking but because they couldn’t think of anything else to say about me.

But then there was the all-important matchup: Who was the better climber? All the humorous comparisons were easy to brush aside, but this comparison went right to my ego. Superficially, we were equally strong: Alexander tended to be better on athletic, overhanging routes due to his shorter levers, while I was stronger on slightly overhanging, crimpy face climbs. Most often, however, it came down to the day’s performance. If you listed the routes we ticked that year as a basis for comparison, my brother came out on top. In climbing and life in general, the more structured individual thus always focused exclusively on one project at a time. On the other hand, I was often too playful in my approach and creative in my implementation, letting myself get too excited by multiple projects at once.

This was also the case come autumn of 1991. I checked out this route, then that route, then I tried another new project while Alexander concentrated all his energy on sixty-five feet of rock at the Schlangenfels cliff in Karlstein. When the temperatures finally dropped, offering the necessary friction, he climbed his first route in the lower eleventh grade: Shogun, a 5.14b. That got me started, and I was suddenly motivated to be disciplined and more focused. I also wanted to break into this next level of climbing. This inner competition pushed us brothers to strive for the next hardest thing.

After a subsequent winter of hard training on our system wall, I repeated Shogun surprisingly quickly. My redpoint burn was crazy. I campused through the right-handed slopers, the crux of the entire route, and only when I was clutching the finishing jugs did the realization kick in that I had done it. Everything had felt so easy, filling me with an inner understanding that this climb had by no means been at my limit.

Alexander, who belayed me on my surprise send, was grinning from ear to ear. “Nice one, Thomas, that was fast!”—“Ahhhh, Alexander, that was unbelievable. Suddenly, I was hanging off the jugs. I cannot remember getting there!”

All he had to say: “I can only tell you that it looked too easy, as if you were climbing 5.12!” It was an experience I would have time and time again: with proper preparation and rehearsal, if you do something at your limit, it can feel easy, while a lower-graded route that looks easy on paper can feel desperate.

At the time, our lives still felt inspired by our success on Shogun: full of surprises and always in the fast lane. I was a qualified mountain and ski guide: I had a loving girlfriend; my brother and sister, Karina, who climbed with us sporadically; an awesome climbing community; and the Kugelbachbauer.

We always had a plan, a line, and a project, especially in Karlstein. After a successful ascent, the route was toasted with the clinking of beer steins at the Haidi vom Kugelbachbauer and then christened with an appropriate name: Wotan Wahnwitz, Easy Rider, Sexplosion, Sex on the Rocks, No Woman No Cry, Violent Femmes, Halber Mensch, Skyline, or Hypergalactic Donnergurgler. We spent much of our time tirelessly hunting for new projects. Bolt, clean, work, send, and off to the next. From the outside, we surely looked restless, sprinting from one project to the next. Alexander found a fantastic line on the Göll west face, while I spotted something on the Feuerhorn north face, ten pitches, ultra-beautiful—it looked impossible.

I had discovered this line years ago, before my time in the Bundeswehr, when 5.12 had been my upper limit. Back then, Alexander and I were already addicted to first ascents. We climbed Utopia and Dave Lost on the north side of the Reiteralm. Once those were done, we were back on the hunt until I spotted this line with slabs, cracks, and blank sections on the Feuerhorn. It was love at first sight, and from that moment on, I lived in fear that someone might snatch this line away from me. Even though I was out of my depth on this wall, I immediately placed a first bolt. After that, I calmed down because it was now my project, reserved for me as if marked by a dog urinating on a fire hydrant.

It took me a few years to equip the climb, but in the end, I’d created a piece of art consisting of ten fantastic pitches just waiting for a free ascent. (I bolted this route in sport-climbing style, installing the bolts on rappel; however, on alpine walls and in big-mountain terrain like the Himalayas, we’ve always had a strict ethic of climbing ground-up, to preserve the adventure.) My masterpiece, taking my skills as a sport climber and projecting them onto an alpine face, seemed to be X+ (5.14a) or even harder. The difficulty stems from the sum of so much intricate climbing, until you reach a breather 650 feet above the ground. Then the next 10 feet put you to the test: everything that has come before feels like a warm-up. After this crux, the climbing is still hard but manageable. Although the crux moves are unforgiving in their compressed nature, they also embody all that is best about climbing.

You must lock off tiny underclings, perfect incut crimps, and gastons, making big moves between the grips. The only downside is the minuscule, sometimes slippery footholds. Hanging onto two handholds, you need to forget the fatigue from all the extreme climbing below and wait for your inner voice to order you to “go”: now everything has to fall into place; you only have enough in the tank for one proper burn.

Silence

I trained all summer with one goal: my route up on the Feuerhorn. I was mostly alone on the wall, working the moves on a static rope. Alexander sent his route in Berchtesgaden and said it was the most challenging thing he had ever done: 8c+ or 9a. This put it up there with Hubble by Ben Moon and Güllich’s Action Directe. He named his masterpiece Om. Of course, there was some discussion about whether a Huberbuam could perform such feats in the first place. But nobody could prove the opposite if nobody repeated it. And since Berchtesgaden is not on the climbing world’s map, Om slumbered on unrepeated for quite some time.

Of course, I wanted to follow suit, maybe not with a high-end sport climb but with an alpine route in the upper tenth degree of difficulty. The conditions were good, the cool temperatures offered excellent friction, and Roman, a good friend from Ruhpolding, held my ropes for my first redpoint attempt. I immediately sent all nine pitches to the rest point before the crux. “Then go get it—get it over with before winter kicks in,” I quietly said, chalking my hands and blowing the excess powder off my fingers.

I slid into the complex series of moves, which I had rehearsed for days. With seemingly limitless power, I locked off the undercling, did a slight crossover, sorted the fingers into the incut slot, fully crimped, and pulled far right to an incut sidepull, and then brought my feet over onto the tiniest of dimples—all to get my body into the launch position for the most complex move. Now I spanned far left into a shallow dish, which fit just my index and middle finger, and locked off. “Ahhhhh, Thomas, pull, don’t let go!” Roman’s voice drifted up from the hanging belay below. At that moment, my foot popped, and I fell, hitting the end of the rope fifteen feet below the crux.

“Fu . . . I was so close!” I was happy and surprised that I had gotten this far, but disappointed simultaneously. “Man, all I had to do was grab the good hold. I could see the jug in front of me.”

“Take a break and try again!” Roman recommended.

“For sure, I’ll try. I won’t give up!” But a slight melancholy was already audible in my voice.

With such a feeling surging in your gut, performance seldom follows. But there was something I was missing at that moment: This repeated popping of my foot, only inches from latching the exit jugs, was a turning point. If I had sent there and then, I would have given this route a proper name, celebrated a successful climbing year together with Alexander and our friends, and probably our rock ʼn’ roll would have continued—studying in Munich, training, partying, and training again. We would have cheered each other on and, after a successful climb, would have philosophized, slightly intoxicated by beer, about what name to give this new, hyper- vertical work of art. What wild times those would have been.

But everything turned out differently. Winter came too early, and the Feuerhorn route remained unclimbed. This bullshit situation weighed heavily on me, perhaps also because our mental calculus of achievement, which was fed by 8b and 8c rock climbs, was massively out of balance. Thus, this fall on the Feuerhorn was not just fifteen feet onto the rope, but a plunge into a dark void of sadness. I suddenly questioned everything: this rock ʼn’ roll lifestyle, my studies, my goals, my career prospects. To top it off, my girlfriend dumped me for another guy, and soon I was drowning in tears.

It was almost unbearable, and I returned to the solitude of my chilly north face of the Feuerhorn after a long, dreary winter in Munich. I climbed alone, on a fixed rope, living as a hermit in this vertical arena, rehearsing the moves daily, inhaling the silence, the wind, and the whistling of the birds. This gave me the peace of mind I had hoped for because, letting me leave everything that annoyed me in the valley below.

But this state only lasted as long as I was in training mode. When I planned my first ascent, the stress returned because I wanted to prove to myself and the world that I had not forgotten how to climb. On the approach, I already knew that I needed to be in a better headspace. What good are massive biceps if your mind is shit? As Wolfgang Güllich put it, “The most crucial muscle in climbing is the brain.”

What good are massive biceps if your mind is shit? As Wolfgang Güllich put it, “The most crucial muscle in climbing is the brain.”

How right he was. Most of the time, I’d launch into the crux lead feeling like I was unlikely to reach the top, and with such an attitude, I may as well have stayed at the belay. But how do you explain that to your partner, who was motivated beyond belief: “Today, Thomas, it’s going down; I’ve got a gut feeling!” Of course, I couldn’t say anything negative and didn’t want to look like a person riddled with doubt. So I’d bury my anxiety and hop into the passenger seat.

On try after try, things would go smoothly until the tenth pitch, where again history repeated itself: At that damned smear, my foot would pop, and seconds later, I would be hanging in my harness, screaming, raging at my inability. I couldn’t wrap my head around having failed yet again just inches from the finish line. Soon the anger vanished, to be replaced by resignation.

Permanent failure had caused severe disorientation, which led me to quit university. I moved into a flatshare in Traunstein and took work as a mountain guide, and typically leading my clients up the East Face of the Watzmann. Soon after, I got a nine-to-five at an experiential-education facility close to Berchtesgaden; their base was an old, stately home in a beautiful location with a view of the Göll, Watzmann, and Hochkalter. But during a liquidation case, this property was to be sold.

I almost didn’t dare give voice to the notion buzzing around my head about living and working here, in this place, which could be turned into a conference hotel, offering guests one-of-a-kind mountain adventures. These activities could support me in better mastering my inner hullabaloo because nature is the best teacher anyway.

That’s it. It would be perfect.

The End of Silence

I told this story to my father, who in the meantime had finally parted ways with the rigid banking business. He’d begun tinkering with real estate on his own, buying old properties, renovating them, and then selling them off for a profit. He was finally free, self-employed, and loving it. He was not only enthusiastic about the property, but also about my vision. It didn’t take long before this property was ours, and I knew that I’d finally found my place in this world. Now I could shape my future in the mountains, just as I had dreamed of as a child.

I moved to Berchtesgaden for good, and with Mic, a good friend and fellow mountain guide, I was soon immersed in planning out our new project in this uniquely beautiful space.

In the meantime, I trained a lot with Rudi on my new home climbing wall, was a daily regular at the Kuckucksnest, was invited by the Ganghofern to join in the wildly archaic custom of the Buttnmandllauf (with the “demonic” masks), and slowly found my way into the Berchtesgaden climbing scene. And yet some stubborn Berchtesgadeners kept telling me that I would always remain an “outsider,” because only those born and raised in the valley were real locals! I could live with that. My thoughts were freer than ever, and what I could not have imagined months ago, I went for today: I returned to my personal drama on the Feuerhorn, but this time with a completely different energy and mental attitude.

Alexander belayed me on the first attempt. I got back to that darn spot, and this time my left foot didn’t slip; it held, stuck to the tiny foothold now black with shoe rubber, and the next move suddenly felt very easy. Finally, those few inches were no longer missing. I held the exit jug. I shouted out my joy, and the Feuerhorn, the mountains, Alexander, and the alpine swifts rejoiced with me and returned my shouts as an echo.

I held the exit jug. I shouted out my joy, and the Feuerhorn, the mountains, Alexander, and the alpine swifts rejoiced with me and returned my shouts as an echo.

I named the climb The End of Silence because it was truly the end of my inner vertical loneliness and silence, and graded the individual pitches from VII+ (5.11-) to X+ (5.14a). However, as a multipitch route, I dared to dish out an XI- (5.14b), given the cumulative fatigue and the fact that the crux came on pitch nine. For me, it was the most difficult thing I had climbed. This subsequent assessment of an overall rating was based on my experiences with Shogun, Mercy Street, and Princess and the Hero, all routes at the upper end of the scale.

At the same time, Beat Kammerlander established the multipitch Silbergeier in the Rätikon and Stefan Glowacz climbed his multipitch Des Kaisers neue Kleider in the Wilder Kaiser, and they also rated their routes X+ (5.14a) without giving an overall rating. Klettern magazine presented our three routes as the “Alpine Trilogy,” with my route being the most difficult, at least numerically, because of the suggestion of an overall rating. This was provocative, especially for Glowacz. After the tragic fatal car accident that took Wolfgang Güllich’s life in 1992, Glowacz was undisputedly the most famous rock climber in Germany. And now we— the simple Huberbuam—were sharing the proverbial red carpet, myself with The End of Silence, and Alexander with Gambit and Om. Our climbs caused much debate within the climbing world, and I was accused, for reasons of marketing and showmanship, of using the overall rating to artificially inflate the grade of my route. Alexander was likewise criticized for grading his climbs with the holy 9a (5.14d) label without ever having repeated any established 9a’s first.

Glowacz did not like this at all, and he immediately set his bearings for the Feuerhorn. Up on the crux pitch, he found a shallow pocket a few feet left of my crux and thus an easier solution; making quick work of my route, he publicly downgraded The End of Silence to X- (5.13c), not without adding: “If you stick your neck out the window, don’t be surprised if you are hit by oncoming wind.” That really cut deep, and I was simply lost for words. It wasn’t until years later, when the Alpine Trilogy had become a coveted feat and must-do for many a well-known climber, that The End of Silence was upgraded to X+ (5.14a), despite Glowacz’s solution.

Freiheit: In the Mountains, There is Freedom

By Thomas Huber

0 Comments