Age brings wisdom, insight and mastery. That’s a pleasing fairy tale used to sell Viagra, luxury cars and Dos Equis.

Age may bring some benefits, but it also brings weakness, pain, injuries, distractions—a general diminishment of all things associated with athletic performance. All semi-serious amateur climbers wonder why he or she should try hard at something so silly—to suffer and sacrifice and take risks when there is no monetary compensation, virtually no notoriety and certainly no guarantee of any real success. But when you reach that so-called certain age, this question becomes even more pressing as the point of it all becomes yet harder to see, even with the now-required reading glasses. For the growing population of child climbers, the word for the day seems to be “PSYCHED!”

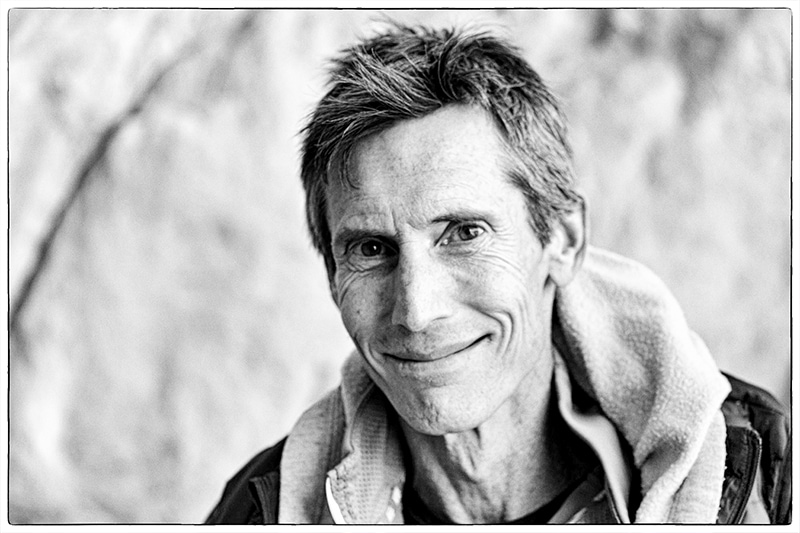

For me, at age 54, the words that come to mind are more like “Ouch!” “Damn!” and “Take!”

Sure, even as one ages there remain many great things to love about climbing. There’s the excitement and wonder of visiting the many awe-inspiring climbing venues around the world. There’s the sharing of fears, successes, and jokes with some of the best people in the world. Those certainly have high value. But they don’t require trying really hard. They don’t require day-long training sessions and a seemingly endless series of attempts that result in failure and frustration. They don’t require pushing to find your absolute limit.

And yet, here I am again, desperately trying to recover at a terrible rest, on a climb that has consumed me for the past two years, at what I am pretty sure qualifies as my absolute limit. As I try to dial back my breathing and heart rate to something below red-lining, I ask myself how this happened. How did I return to this place, a place I know all too well—a place furnished with frustration, disappointment and repeated failure?

About three years ago I told myself I was going to stop doing this sort of thing. By “this sort of thing,” I mean trying to climb something that is too hard for me. And by “too hard for me” I mean something that if I dug deep enough I might be able to do, but only with enormous expenditures of time and effort. I had completed a climb (Reverse Polarity) that had turned into an extended siege lasting over a year. It had beaten me down both physically and mentally. The only real advantage I have in climbing—a tenacity that, in truth, is just the manifestation of an obsessive-compulsive pathology—was largely depleted. Success was sweet but the price was high. I strongly suspected my efforts were really just a delusional attempt to deny the fact I am getting O-L-D.

Okay, I thought, enough of that. Hard climbing comes with an expiration date, and mine had come and gone. I shifted to routes I could climb fairly quickly—mid- and low-range 5.13s and fun boulder problems. It was time to enjoy climbing the way most people do. Success was never really in doubt, and perhaps I was a little bored … but I did not miss the drudgery.

Climbing was fun again. Predictable, but also enjoyable. Mostly.

“You really should check it out, Bill. It’s more your style, much more endurance-oriented.”

“Just get on it and just see what you think. It has to be one of the best 14bs in the country.”

“DUDE, CHECK IT OUT!!!”

I’d been hearing these words over the last few years about Golden For A Moment, an increasingly famous climb at the Cathedral, a large limestone cave just northwest of Mesquite. The climb, it seemed, had hired a marketing firm to promote its wonderfulness. I remember when the route (bolted and prepared by southern Utah hardman Todd Perkins) was a long-standing project that various friends were trying. But now it had become a must-do route for every top climber in the country. Thankfully, having never been a top climber, I had no problem ignoring the marketing campaign.

In the spring of 2013, however, I found myself gaping up at the headwall of Golden, watching a friend, Dan Mirsky, work a harder variation. It really did look incredible.

“C’mon, man, GET ON IT!!”

What the hell, why not? I told myself that I’ll just come down after a few perfunctory moves. …

Wow! Cool holds …

Feet right where you need them …

Could see getting into a rhythm through this section … And, holy shit, does rock gets any better than the sculptured limestone pockets on this top crux?

Lowering down from the top, I had to admit the quality impressed me. But at the same time, there were the powerful sequences, the horrendous so-called rest near the top, and an upper crux where I would undoubtedly fall forever. Nope. Not for me. The climbing terrain was beautiful, but it was no country for old men.

Still, certain climbs can act like psychological viruses, infecting your brain with obsessive thoughts despite our best efforts to stay sanitized. As I hiked down from the cliff through a river wash scarred by years of hydraulic violence, my brain started playing with conjectures.

“Well, if I were to try it, what would need to happen?”

Ideas started taking shape—initially in the form of very crude plans that soon became something more like strategies. I could feel the old engines of motivation coming to life; the psychological gears and cogs that make up the drive shaft of my climbing career slowly started turning over, picking up speed. Ducking under a massive cottonwood tree, I grinned into the fading sunlight:

Fuck yeah, this thing might be worth a go.

Broken down, Golden starts with a 5.13a to the best rest in the world, to something like a .13d, to the worst rest in the world, to a V8 crux, to an easier boulder problem to the anchors. To succeed on the route, I knew that three things would need to happen:

1) I would need to get to the upper (bad) rest relatively fresh

2) I would need that rest to feel like an actual rest, not an enhanced interrogation technique, and

3) I would need to wire (as much as possible) the crux boulder problem. All of this would take a lot of work, and I contrived a scheme that involved spending the next fall learning the climb, the winter bouldering to get my power up while also working simulations of the crux, then trying to climb it for real in the spring. I would need to concentrate my training on power endurance, flexibility, and recovering from horrible rests. I hoped that by April I would be prepared to, as they say here in Vegas, “go all in.”

All of this became reality. I worked out a lot of beta, had a good winter bouldering, and then, in February of 2014, went up to see how things felt. The good news: things now seemed significantly easier than they had in the fall. The bad news: easier was still a long, long way from doable. Back to the training drawing board.

Ah, training. People have asked me how I’ve avoided injury while climbing as long as I have, and when I tell them what I do, they look deeply disappointed, like they just found out I use MySpace. Their disappointment is driven by just how misguided my approach is widely known to be, both in terms of quality and quantity. As for quality, much of what I do (like weighted fingertip pull-ups, and using grip devices) is often characterized as a silly waste of time by the experts. And the total amount of stuff I do in a given session is equally derided as excessive and counter-productive. Insofar as the current meme is “train smart, not more,” my training must be remarkably stupid.

Having been around for the rollouts of most major training innovations, including fingerboards, climbing gyms, campusing, system training, interval training, periodization, 4 x 4s, and so on, I have become something of a hoarder of routines. If something sounds worthy, I simply add it as part of the regimen. Some days I go big, and the overall training (including warm up and rests between sessions) can last as long as 14 hours. Is this wrong-headed? Perhaps, but I would recommend taking everything currently “known” with a grain of salt.

As someone who has witnessed many cycles of “we now know X is essential” being replaced 10 years later with “we now know X is a bad idea,” I can assure you that we still have a lot to learn. I also recommend occasionally thinking outside the remarkably trend-driven training box.

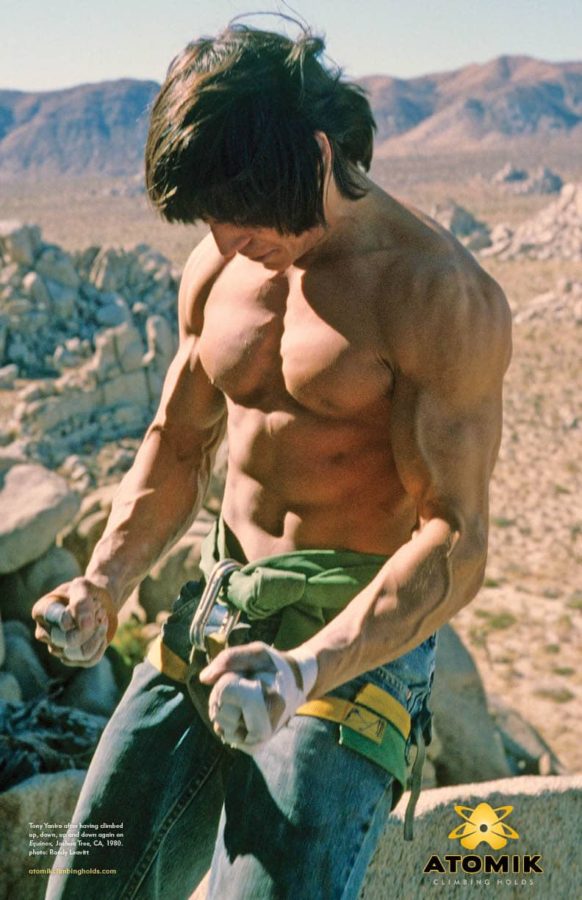

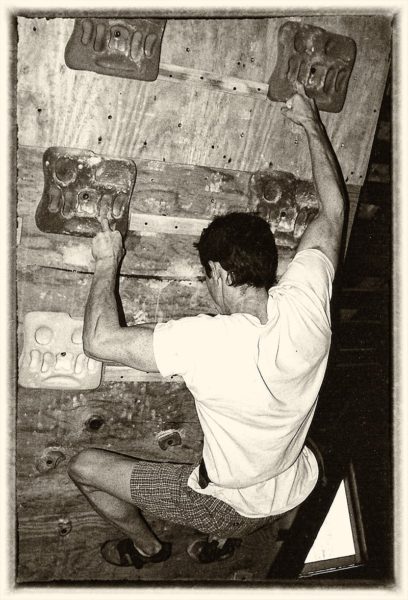

In the last century, my training contemporaries were people like Yaniro, Leavitt, Hill, Gullich, Bachar, Watts, and Speed. Before there were climbing gyms and coaches and training manuals, these people were very good at discerning why they were failing on their projects and then contriving a device or system that targeted those weaknesses.

As a teenager, I nailed wooden blocks to the rafters in my home to develop my own regimen. Ever since, that is what I do; that is how I train. I do understand why so many climbers are now turning to professional coaches and trainers for advice, and I’m confident that if I did the same it would help me improve.

But I am also confident that if I started relying on others, it would make me miserable, not simply because I hate to be told what to do—though I do—but primarily because it would rob me of a dimension of climbing and training that I find tremendously gratifying. Coaching is not so different from teaching, and my passion for the latter in philosophy is matched by my passion for the former in climbing—even if the only person I’m coaching is myself.

Going through the process of discerning exactly what physiological, psychological, and skill transformations need to occur for success on a particular climb, and then contriving and implementing a strategy that will create those transformations—that process for me has always been one of the most fulfilling aspects of sport.

Or so I thought. Doubts come easily when failure looms large. The spring of 2014 came and passed. Fellow climbers sent Golden in good style. And despite getting very close, as the thermometer at the crag started reading 80 degrees, I started to regress. As hard as it was to admit, my program had gotten me close, but not close enough. Beaten down, I fell into a dour mood as I walked down the canyon for the last time in late May. Everything I believed about training and strategy was moved to the mental category labeled “Uncertain.” And that wasn’t the worst of it. Another part of my brain—the harsh and nasty and unforgiving part—was telling me that “Uncertain” was being charitable.

The gloom lasted until June, when I arrived in Rifle for the summer season. New editions of the Rifle guidebook are notorious for dropping letters on grades, reducing your proud 5.13c send to a mere 5.13b with a couple of key strokes. But for me, the letter that got dropped in Rifle last summer was the “k” in “funk.” Rifle in the summertime is all about hanging with good friends, cook-outs, drinking beer, sharing stories and climbing routes of all different grades and styles. It was rejuvenating to reconnect with the culture of climbing at a major area. It was also good to enjoy a series of successes on routes that weren’t especially hard but were nevertheless interesting and challenging.

Yet I kept thinking about Golden. How to train for it, how to modify my beta, what my approach in the fall should be. It was always there in the back of my mind.

Returning to Nevada in the fall, some of us from Vegas decided to get an apartment in Mesquite to make projecting in the area a little easier. The “Villa” was sparsely equipped, but included a hangboard and rowing machine for warming up. My roommates—Mike Doyle, Rob Jensen, and Lisa Davidson—all had long-standing projects at the VRG and as autumn progressed, all of them were going through their own trials and let-downs and frustrations.

Up at Cathedral, I also climbed with Anne Struble, who was trying to become the first woman to climb Golden. Doing a climb at your limit is certainly a physical trial, but the real suffering is between your ears. It is all too easy to deceive yourself into thinking you are much closer than you are, setting yourself up for disappointment and frustration. While I tried to make my own incremental progress on Golden, I watched my cohorts repeatedly fall, shake it off, and get right back up. These folks, and various others I climbed with, were doing something that I deeply admired and respected. Like me, they had committed themselves to an endeavor they knew would really test them, and that might prove to be a tremendous waste of time and energy. And yet they kept picking themselves up off that mat, dusting themselves off, and getting ready for the next round. This tiny community and their relentless tenacity with their projects, even while juggling stressful work schedules, became my main source of inspiration, optimism, and invigoration.

Regrouping at the Villa after a hard day, between jokes and beers, we would share what went right, what went wrong, and mostly what needed to be fixed. I felt honored to be striving among them. It might seem odd to be grateful for membership in a club whose members are failing most of the time. But it was through the process of failing their way to success that the members distinguished themselves as strong and really great individuals. When we heard news of the success of Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgenson on the Dawn Wall, a project that had taken them seven years to complete, we all felt energized. When people eventually succeed after trying something for an extended period of time, something that involves repeated disappointments, then, no matter how objectively hard it is, they have accomplished something beyond an athletic achievement. They have made a statement about what they are made of—about a type of strength that has nothing to do with forearms. Watching my friends achieve that success on their own projects was encouraging and motivating. Of course, at the same time, it threw into sharp relief my own continued lack of success.

To any young crusher who is all about sending things fast, this homage to projecting might seem like a feeble attempt to put a positive spin on floundering. Fair enough. Because there is also a lot to celebrate in the raw strength and eagerness that many of the top young climbers exhibit. To them, projecting means trying something twice, maybe three times. Although I am often exasperated by their naïvete, I also admire their cockiness, their aggressive energy and impatience that drives everything forward.

In fact, I can remember that sort of cockiness on a sunny day in the fall of 1979. I was an overconfident teenager who thought he needed to check out the new grade of 5.12. I had seen a picture on the cover of Mountain magazine—Ray Jardine on Separate Reality—and the climb looked incredible. Getting on it was foolish, given my lack of experience, but my chutzpah trumped what little sensibility I had. I tried the route once, did not succeed, but saw that it was conceivable. As I lowered off, another rappel line appeared and rockstar Tony Yaniro poked his head under the ceiling, soon to be joined by Colorado hotshot Jim Collins. My cockiness morphed into self-consciousness, anxiety, embarrassment. I promised them that after a brief rest, I would go up and clean it when I fell so they could properly have the route to themselves.

All extended athletic careers are punctuated by moments that Kant, and later Gumbrecht, characterized as instances of the “sublime.” They are the rarest of times when luck, skill, and some degree of gumption combine to create what is best described as a fleeting but undeniable moment of grace. Some professional athletes can conjure several of these in their career, and that’s why they are superstars. But even for us rank amateurs, there are the rare instances when it all clicks and body and mind enter a state of communion that transcends our normal mediocrity.

As I moved across the roof of Separate Reality that day, I experienced such a moment. The jams felt solid, my arms felt strong, and everything that is great about being a 19-year-old kid in love with life and adventure and the thrill of going for it culminated in one of those rare moments. I pulled over the lip and sat there breathing hard, not really believing what had just happened. Bill Price walked over, reached out a hand and congratulated me.

Looking back, memories like those still make me smile.

Of course, memories, great as they are, are representations of the past. They are not representations of the present, and they are certainly not representations of the future. Still, memories can motivate.

Thinking about that kid made me feel a little less tired at the horrendous excuse for a rest on Golden. It made me relax and recognize that whatever happened, even on my umpteenth attempt, I have been incredibly lucky to have spent my life in a sport with, quite frankly, some of the very best people, at some of the very best venues, having many of the very, very best times. Yeah, it’s all good. I shooed away the doubts and distractions and insecurities of age and focused on the task at hand.

Right hand into gaston, now press up on bad left foot and flag. Left hand grabs the wide pinch. Bam. As I executed the all-too-familiar routine, the half-century-old neurophysiological shell I inhabit reached some sort of agreement with the 260-million-year-old remains of micro-plankton. Everything clicked. Although my right foot popped off a key foothold, that same cocky kid somehow reappeared and a feeling of self-assured disregard took over. Screw it, I don’t need the foot, I’ll just power through to the rest hold that has eluded me for two years. And so I did.

Predictably, my conjured youthful confidence was short-lived. The rest holds that normally seemed big and positive now felt slopey and greasy. My core was drained and my leg started trembling as a sense of panic swelled up. I realized I probably didn’t have the strength for the final boulder problem to the anchors. Shit.

And then, while desperately trying to recover, 40 years of climbing experience kicked in and the inner monologue shifted to my not-so-alter ego, the coach. His commentary was well-practiced and no-nonsense: You’re not a goddamn rookie and you have been here before. Just calm the fuck down, pull your shit together, and do what you know how to do.

As I launched into the final sequence, it became easier to grasp why I love climbing, why I love pushing myself, and why I am still trying hard, even at this old age. Despite the often extended series of failures and frustrations, it is a process that also includes a distinctly high quality of happiness and kinship with people I love. As Aristotle insisted long ago, striving is an essential element of what the Greeks called “eudemonia”—a life lived well. I am indeed in denial about my age. But as I clipped the chains on Golden, I couldn’t think of a better sort of denial.

This article was originally published on April 14, 2015.

0 Comments