In 2019, a group of Palestinian climbers and a few international friends hiked out to a local crag near the West Bank city of Ramallah to climb, camp, and enjoy a respite from the city. In the evening, as dusk settled over the quiet valley, the climbers lit a campfire.

Suddenly flares launched from an opposing hilltop, illuminating the valley in a harsh, bright light. Soon thereafter a dozen Israeli Defense Force (IDF) soldiers appeared out of the darkness and surrounded the climbers. They were dressed in full combat fatigues and carried M4 assault rifles.

“You cannot be here,” said the commanding officer. When asked why, the soldiers provided no reason.

The climbers were told to sit on the ground and, one-by-one, were forced to pose for mugshots. The soldiers took their IDs. Finally the climbers were told to leave. They were marched back down the valley with the soldiers’ weapons’ menacing red laser dots on their backs.

The climbers, all close friends of mine, were recreating in a way that would be familiar to any climber. But the bleak reality of Palestinian life under Israeli military occupation is such that there is not a single place my friends could have gone to camp that would have been guaranteed safe from this brand of harassment. In fact, it easily could’ve been worse.

As the climbing world has important and necessary conversations about inclusivity at our crags, I want to draw attention to a climbing community that, though geographically distant and relatively small, experiences harrowing injustices every single day, which I suspect most Americans don’t know about.

I moved to Palestine in 2014 with my college friend Will Harris to develop a grassroots climbing community. Will and I had studied Arabic during a semester abroad in Jordan and were inspired by the nascent outdoor climbing scene there. One month after graduating from college, we moved into a tiny apartment in Ramallah with very little besides a pile of donated climbing gear.

We hadn’t gained much traction on the fundraising front but we had a clear vision for what it would take to establish a space for Palestinian climbers. We knew building a small gym, establishing crags, and providing instruction and mentorship would be crucial. After bolting a few routes, we advertised a beginner climbing trip on Facebook and were overwhelmed by the amount of interest.

There are now hundreds of routes at five distinct new crags, and thousands of people have visited the Wadi Climbing gym in Ramallah and joined our climbing trips. There is a tight-knit, motivated, self-sustaining climbing community whose members include Bedouin kids who would crush your project in Crocs and serve you up some crag-side qalayat bandoora (fried tomatoes) the next moment.

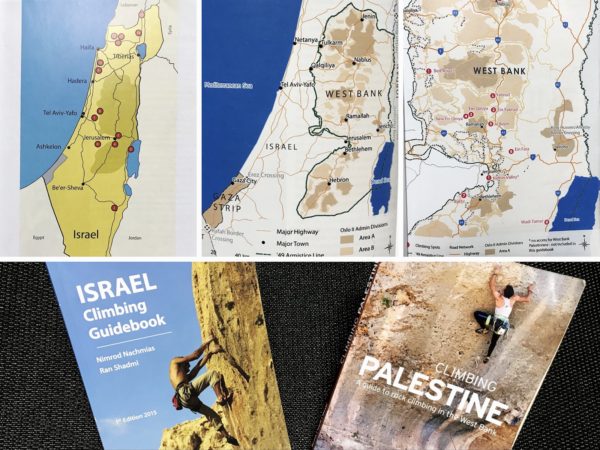

It also took years of living in Palestine to fully understand the injustice of life under Israeli occupation and how it affects Palestinians. Separate guidebooks, separate crags, and different approaches are only the tip of the iceberg that is life for Palestinian climbers.

Climbers who travel to this region and only stick to Israeli channels during their visit not only run the risk of missing out on eating fried tomatoes with kindhearted Bedouin kids, they will miss seeing the extent of injustice Palestinian climbers face while merely pursuing their passion.

Take Adam Ondra’s 2017 trip to the region. Ondra’s visit virtually ignored half of the people that live in the region. In addition to climbing at sites like the Nezer cave in northern Israel, Ondra crossed the Separation Wall to climb at Ein Fara, only 20 minutes from Ramallah, the heart of the nascent Palestinian climbing scene. Not once on his trip did he visit or climb with Palestinian climbers.

In a striking image from this trip, Ondra and professional Israeli climber Ofer Blutrich are standing at the Dead Sea with the words “Climb Free” etched into the mud caked onto their backs. The photo was meant to advocate for climbing access in Israel, but it can easily be read as a kind of insult to Palestinians, who can’t “climb free” and don’t have the choice of being #beyondconflict, the hashtag for this trip and the title of the subsequent YouTube video documenting Ondra’s visit.

I’ve wondered to what degree climbers, especially those with large platforms, are obligated to consider the impact of their visits to conflicted regions. Climber and social media influencer Nate Murphy wrestled with this same question on his 2019 trip to Israel. His documentary ”Pillar of Oppression” is an empathetic, nuanced exploration of the topic. He concludes that “complicity is not a moral option,” which I think is spot on.

The real insult of Ondra’s trip is that it was a missed opportunity for one of the best and most widely respected climbers in the world to use the power of his platform to make people more aware about what life is really like for Palestinians. Especially for us Americans, many of whom don’t realize how greatly our tax dollars subsidize this oppression, the chance to see a more honest depiction of life in Palestine would be a chance to make people care more about correcting these injustices. With such heavily one-sided coverage of the situation here in the U.S., it’s understandable how few people understand what it means to live under a modern apartheid regime.

Let me briefly try to paint a picture of the magnitude of Israel’s violent colonial enterprise in the West Bank, which began in 1967 when Israel took control of the territory from Jordan. Since then, life for Palestinians has grown slowly and steadily less free. A complicated system of permits, identification papers, checkpoints, policing, home demolitions, forced displacement, and surveillance has ensured Israel’s total dominance over the 2.1 million Palestinians living in the West Bank. This is to say nothing of the Israeli siege of the Gaza Strip and the abject misery of its entrapped population. This affects the lives of Palestinian climbers in every conceivable way.

Shortly after 1967, Israeli “settlers” began moving into the West Bank while still enjoying full rights as Israeli citizens. Today over 600,000 settlers live in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. They can vote, travel unhindered in most of the West Bank and Israel, visit the ocean, fly out of the airport, and are tried in civilian instead of military courts. The settlements, which look like gated suburban communities, often connect to mainland Israel via a series of roads that are closed to Palestinians. Some settlers are religious fundamentalists who harass and attack their Palestinians neighbors—including those trying to recreate outdoors.

Just last week, six masked settlers beat a group of Palestinian mountain bikers with rocks and clubs just for biking on a trail near a settlement. (Note: all trails in the West Bank run near the ubiquitous settlements). This kind of violence is a common occurrence in the outdoor community here. It is also often overlooked by Israel, and therefore escapes any consequence.

For Palestinians, access to crags and trails is not an assumed right but a tenuous and complicated ordeal. For example, Palestinians can only reach the climbing area Ein Fara by hiking 45 minutes around an illegal settlement. Meanwhile, Israelis and foreigners can drive through the settlement to park at the base of the cliffs. This particular settlement is built on stolen Palestinian land (some of which was once owned by the grandfather of a Palestinian climber).

Another West Bank climbing area called Beit Ariye is located within a settlement and therefore Palestinians are not allowed to climb there at all.

During my time in Palestine, we developed a number of crags that are safely accessible for Palestinians in Area A, a small swath of land that remains tenuously under Palestinian control. Even at Area A crags, Palestinians are not guaranteed to be free of the threat from IDF or settler harassment.

If I were to offer a caveat for the traveling climber, it would be to make a genuine effort to experience climbing here through the Palestinian perspective. Failure to do so can perpetuate the Israeli state narrative that seeks to total erasure of Palestinians and their history.

Peter Beinart, a prominent Jewish intellectual who surprised the world by embracing a one-state solution, described what ultimately changed his mind during an interview on a New York Times podcast. He said:

“It was spending time with Palestinians in the West Banks myself. It was a shocking experience to go there for the first time. It’s one thing to understand in the abstract that people can live under a government that can do anything to them without recourse … but when you see what that looks like, day after day, for a half-century: it’s standing in villages about to be bulldozed—not because they’ve done anything wrong but because they can’t get building permits because they’re not ‘citizens’ … It’s talking to families who wake up screaming in the middle of the night because the army comes into their homes because their kids threw stones at the military, which humiliates their parents every day, something my own kids would do… That was a profound experience for me.”

Rock climbing is nothing if not a vehicle for having profound experiences that changes your perspective in surprising ways. These experiences must be curated responsibly, however. In 2017, Yosemite climber Miranda Oakley, whose mother is Palestinian, wrote passionately about the imperative climbers have to think about their political impact on the places they visit.

There are many reasons to visit Palestine, and rock climbing is an incredible way to explore this fraught but beautiful land and build relationships with the people who live here. With a foreign passport, visitors can travel freely between Israel and Palestine and will find welcoming locals on both sides. Ultimately, as we continue to have conversations about inclusivity at crags, consider the plight of the Palestinians and Palestinian climbers. With more awareness, empathy, and understanding, we’ll be one step closer to achieving that most worthy goal of climbing free.

This is beautifully written and warmed my heart. Thank you for sharing this information about what life is like as a Palestinian.

Sounds like Maranda has politicized her climbing. Harassment is what you get when you raise your kids with knives in their hands wanting to shed Jewish blood, or lets face it American blood unless they agree with your sentiments.