In the 1980s, the rules of rock climbing were in a state of galactic entropy, out of which competing ideas about the fairest and most ethical approach to climbing would eventually be tempered, sometimes violently, to fit alongside ideas about how to best progress the sport’s difficulty. Even hangdogging was a serious taboo at one point. Of course, this concept now feels as absurdly anachronistic as using a Rand McNally map to navigate in a car. But the fact that it once was is nevertheless interesting and makes me consider all the ways in which we, today, take for granted some of our sport’s ethical rules.

To push the ethical boundaries in the 1980s was to also accept the risk that you might just punched or taunted when you get back to your car, yet when it was done in good faith and resulted in an inspiring ascent, nothing more needed to be said.

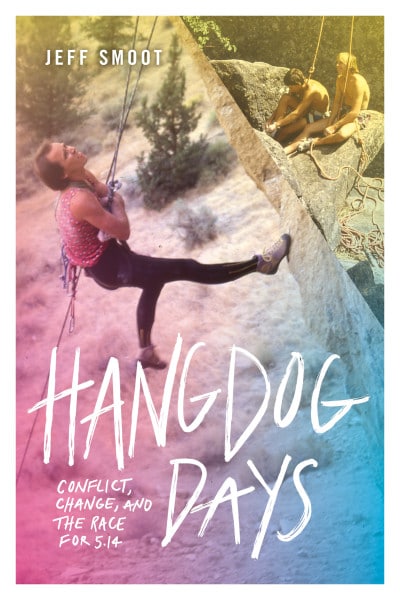

In this spirit, I’m happy to share an excerpt from the forthcoming book “Hangdog Days: Conflict, Change, and the Race for 5.14,” by Jeff Smoot. It describes Alan Watts, the primary architect of sport climbing in America, climbing Todd Skinner’s The Stigma—the name used in this excerpt even though subsequently the first freed pitch was dubbed The Renegade. Says Smoot: “We called it The Stigma still because, although Todd had suggested renaming the pitch, the name hadn’t stuck yet. I don’t think they wanted to legitimize the free ascents; it was a sore subject for sure. It wasn’t until a long time later that people decided Todd’s name was good.”

In this spirit, I’m happy to share an excerpt from the forthcoming book “Hangdog Days: Conflict, Change, and the Race for 5.14,” by Jeff Smoot. It describes Alan Watts, the primary architect of sport climbing in America, climbing Todd Skinner’s The Stigma—the name used in this excerpt even though subsequently the first freed pitch was dubbed The Renegade. Says Smoot: “We called it The Stigma still because, although Todd had suggested renaming the pitch, the name hadn’t stuck yet. I don’t think they wanted to legitimize the free ascents; it was a sore subject for sure. It wasn’t until a long time later that people decided Todd’s name was good.”

Please enjoy, and thanks to The Mountaineers and Jeff Smoot for sharing this excerpt. Hope you enjoy it as much as I did. —AB

The Valley was fairly vacant for mid-August, occupied mostly by foreigners it seemed. Alan had not run into anyone he knew who might belay him on The Stigma so I could take pictures. Then again, Alan had also not run into anyone who might come out, pull down my rope, and shit on it. Still, if we could not find a belayer, I’d be stuck taking unpublishable butt shots, which nobody would want to see.

We went to Yosemite Village and bought food for dinner and the next day. As luck would have it, two Japanese climbers were in front of us in the checkout line. They became very animated, talking excitedly and pointing at Alan as we waited behind them.

“Alan Watts?” one whispered.

“Alan Watts!” the other exclaimed.

“You are Alan Watts?” one of them finally got up the nerve to ask Alan. “Why, yes,” Alan said, quite magnanimously. “Yes I am.”

“Ah. Very pleased meet you, Alan Watts.”

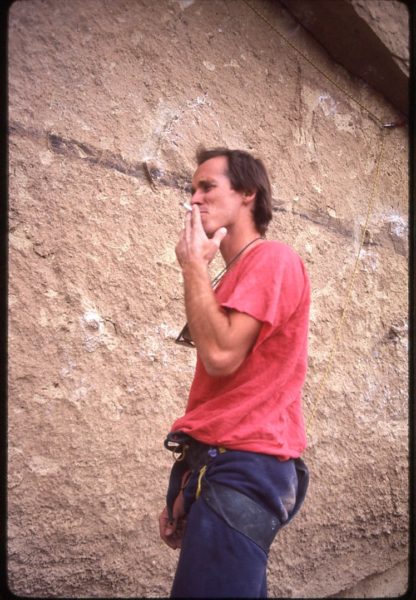

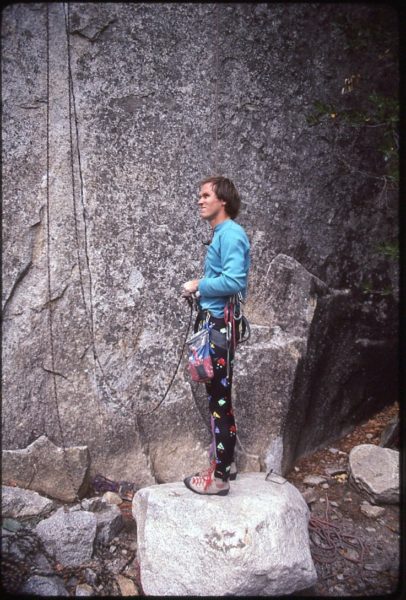

Alan Watts

They bowed deeply and shook Alan’s hand and smiled and laughed like a couple of schoolgirls backstage at a Van Halen concert. They were thrilled to meet the very famous Alan Watts, who was apparently a celebrity in Japanese climbing circles. Alan played the object of adoration with only the faintest hint of mockery.

“Alan,” I whispered, “get them to come with us tomorrow morning. We need a belayer so I can take some pictures.”

Alan arched an eyebrow and nodded.

“So, where are you guys climbing tomorrow?” he asked slyly. “Do you want to come to the Cookie Cliff? I’m going to climb The Stigma.”

“Oh. The Stigma. Todd Skinner. The Renegade. Yes! Yes! We come, okay?”

“Yes, okay. Meet us there at ten o’clock.”

“Okay, yes. Ten o’clock. We see you there right on the time, okay?”

“What can I say?” Alan said. “My fans adore me.”

They bought their groceries and we bought ours and they followed us out to the parking lot, talking excitedly and bowing. Alan had to extricate himself from this socially awkward situation, and did so as politely as possible. They were still standing there, waving, as we drove away.

“Good grief,” I said.

“What can I say?” Alan said. “My fans adore me.”

K urt Smith was standing by the kiosk at the end of the Camp 4 parking lot, talking with a group of climbers. I hesitated and started to walk the other way. Alan started toward them.

“Don’t do it,” I said.

“What?” Alan asked, feigning innocence. “I’m just going to say hi.”

“Don’t.”

“Hey, Kurt,” Alan said casually as he approached Smith, as if he had nothing much to say.

Kurt Smith. Credit.

“Hey, Alan,” Smith said, almost sneering. “You’re working on The Stigma, huh? That route is such bullshit. Skinner didn’t even climb it. He aided it.”

“It’s still pretty hard,” Alan said. “I’m going to try it ground-up, no pins.”

“No hangdogging?”

“I’ll work out the moves,” Alan said. “I already worked on it some yesterday. It isn’t that hard. Have you tried it?”

“No. I wouldn’t try it,” Smith said, now definitely sneering. “It’s a hangdog route.”

“Hey,” Alan said, changing the subject, “I was just up at Donner Summit.”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah. I did Star Walls Crack. It was 5.12d, pretty hard.”

“Yeah?” Kurt said, standoffishly.

“Yeah,” Alan said. “And I climbed Crack of the Eighties.”

Kurt’s eyes narrowed. He stared at Alan.

“You climbed Crack of the Eighties?”

“Just a couple of days ago,” Alan admitted. “It’s not really that hard. Maybe 5.12c.”

“Did you toprope it?”

“No. I led it.”

“Did you hang?”

“Just once to figure out where an RP would fit in. I did it on my second try.”

“That’s bullshit,” Smith said, his face turning red. “My grandmother could have climbed the route that way.”

“I’m sure your grandmother could have climbed the route,” Alan replied, trying hard to suppress a smirk. “It wasn’t very hard.”

Kurt loved that route; his sense of self depended on the mythology of him making the first ascent in perfect style.

Smith’s hands curled up into fists. I thought he might punch Alan, but instead he launched into an apoplectic rage, cursing Alan and the horse he rode in on for desecrating his sacred project. I knew how he felt. Kurt loved that route; his sense of self depended on the mythology of him making the first ascent in perfect style. He had worked on it for years, following the rules, making love to it instead of seducing it, only to have it stolen away from him by this punk, this hangdogger Alan Watts.

“That’s fucking bullshit!” Kurt said. “Bullshit,” he repeated as he strode off angrily.

“Thanks, Alan,” I said as we walked away. “Now we’re in for it.”

“I wouldn’t worry about it,” Alan said. “What’s the worst they could do.”

“I don’t know. Burn your truck? Smear the crack with shit?”

“Wouldn’t that be something,” Alan said thoughtfully.

After Alan’s altercation with Kurt Smith, I braced myself for a torch-wielding mob at the Cookie Cliff the next day, but we arrived to an empty parking lot. We hiked to the base of the cliff and there was my rope, still hanging from the bolt, apparently untouched. I tugged hard on it to be sure someone hadn’t loosened the knot to sabotage me. I sniffed it. Nobody had defiled it as far as I could tell.

“See?” Alan said. “Nothing to worry about.”

It wasn’t long, though, before a strange chorus of owl-like hooting and screeching started up. “Hangdogger! Haaaaang-dogger!” someone yelled.

The hoots continued for a while, seeming to come from a half dozen lurkers camouflaged among the trees and boulders on a ridge a hundred or so yards away, spying from afar but unwilling to reveal themselves.

“Must be some of the locals come to welcome you,” I said to Alan.

“It is awfully nice of them to do that,” he said. “I’m touched.”

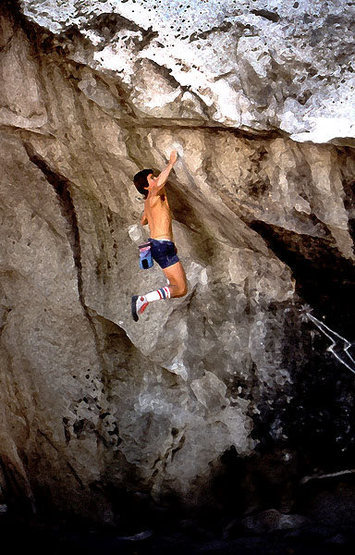

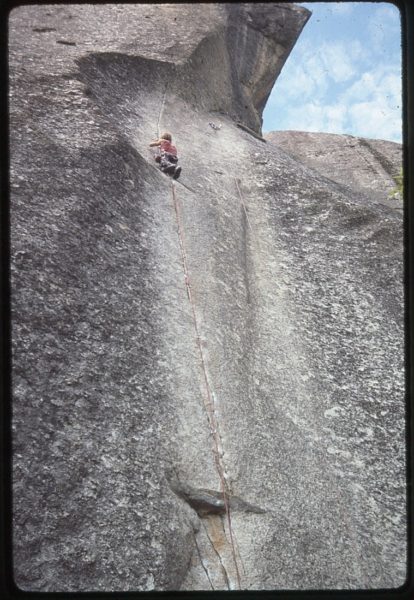

Alan Watts on the The Stigma (5.13b), Yosemite Valley 1985; Copyright Jeff Smoot

Our Japanese friends showed up shortly, and after they assured Alan that they knew how to belay and could understand simple English commands such as “take,” “slack,” and “falling,” I jugged up the fixed rope with my cameras and film and got into position to shoot a couple of rolls of Alan working on the route. Alan put on his rock shoes—a La Sportiva Mariacher on his left foot and a Boreal Firé on the right, to maximize his ability to edge, smear, and jam as needed on the limited footholds. He clipped his minimal rack to his harness loops, checked his knot, made sure his Japanese belayer really, really knew what he was doing, and started climbing.

“What the fuck?” Alan said, looking down at the belayer. “I said take!”

Alan got past his previous day’s high point on his first try before finally falling off. He hung for a minute, pulled himself back onto the rock, rehearsed a sequence, then let go and lowered off to a renewed round of hooting from the woodsy knoll. The Japanese climbers looked off at the hooters and then at each other, puzzled. After a brief rest, Alan tried again, climbing a few feet higher. From his high point, he placed a brass nut specially made by Doug Phillips. It was a standard-issue RP nut, but with a longer cable so it could be placed out of reach of a standard RP—a secret weapon that extended Alan’s reach by six inches and avoided the use of a fixed pin at that particular spot. He clipped the rope in and continued climbing, placing another nut five feet higher. At a point where his feet were just above the nut and he was engaged in a complex sequence of outward side pulls and pinkie jams, he realized he was going to fall off. “Take!” he yelled, then let go, expecting to take a short, controlled fall of perhaps ten feet. Instead, he fell and kept on falling, and didn’t stop until thirty feet later when the rope finally came tight with Alan dangling upside down ten feet off the deck.

“What the fuck?” Alan said, looking down at the belayer. “I said take!”

“Slack?” the belayer asked, preparing to give Alan some more slack.

“Take! Take!”

“Oh. Take. Sorry.”

“Okay,” Alan said, shaking his head then looking up at me, dumbfounded.

“Lower me.”

Alan Watts, Cookie Cliff, 1985, looking over at the hooters wondering if he might get beat up later. (All they ended up doing was hoot). Copyright Jeff Smoot

Alan was fuming but said nothing further. I rappelled down, knowing I was done taking photos for the day. We told our Japanese friends that Alan was going to take a long rest and that I had all the photos I needed, so they didn’t have to hang around all afternoon. They waited for a while, hoping to see Alan climb the route, but we outlasted them. Eventually they nodded and bowed and said goodbye, finally getting that we were giving them the bum’s rush.

The long rest did Alan good. He sent the pitch, repeating Todd’s route up to the ledge on his next try. The crux involved cranking up several small, well-spaced pin scars, including a straight pull on one finger twisted in a slot and one of the most improbable Gaston moves I have ever seen accomplished, applying counterforce to opposite sides of the crack where it was too thin to jam while smearing on minute ripples and edges. He ran out the last fifteen feet to the ledge, placed a cam, then jammed his fingers into the crack above it and levered himself up to a standing position.

“Flip that rope over to me, would you?” Alan asked.

“No way,” I told him. “You should finish it. It isn’t free until it is all free.”

“Damn it, Smoot,” Alan insisted. “Flip me the rope.”

“Hold on there,” I insisted back. “You’ve repeated Todd’s climb, but there’s still twenty feet of crack that’s what, 12a?”

“So?”

“If this was at Smith Rock, would you stop there?”

“No,” Alan admitted.

“There you go.”

Todd had been criticized for stopping short of the end of the crack. Since Todd had fixed pins in the lower half of the crack, he could easily have fixed one more pin in the last twenty feet of the crack and finished the climb. He did not, I suspect, because the hard climbing was over at the stance, and he didn’t want to blow it on the 5.12 moves to the top and have to start over from the bottom. Once he had managed to climb the 5.13 section, he wanted it to be over. I explained all of this to Alan as I held him hostage on belay. Under my implied threat not to lower him off unless he kept climbing, Alan agreed to give it a try.

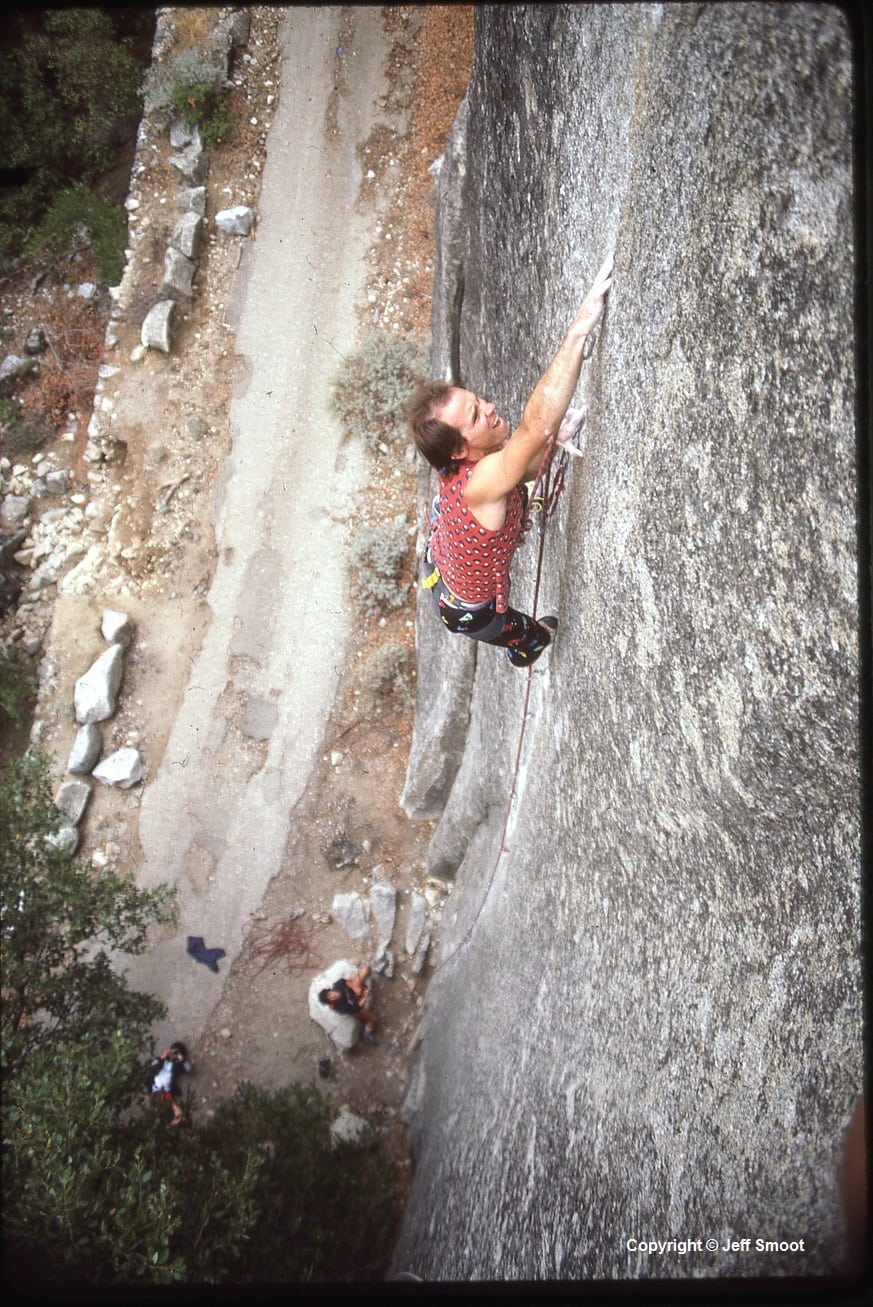

Alan Watts at the stance The Stigma 1985; copyright Jeff Smoot

There was the matter of protection. Alan didn’t have any more gear on his rack. He had carried a pared-down rack with only the gear he needed to get to the stance. The upper crack needed a piton. He needed a hammer. He hadn’t expected to succeed so quickly and wasn’t prepared even to place piton anchors to rappel off. He had planned to rappel off using my fixed rope. The cam he had placed above the stance was protection enough for the moment.

“Okay, smart guy. Now what?”

“I’ll tie some pitons and a hammer to my rope. You can pull them up, then place a pin and go for it. You can place pins on the lead and then climb up to the end of the crack and clip in to the anchor.”

“Easy for you to say.”

“You can do it.”

It went pretty much as I had suggested. Alan hauled up the hammer and pitons with one hand, pulling an arm’s length of rope up and holding it in his teeth, then pulling up another arm’s length of rope, and so on, until he could untie the gear and clip it to his harness. Alan whacked in a piton at the ledge, then free climbed a couple of moves above the ledge, whacked in another pin while hanging off a finger jam, clipped it, did a move, fell, hung, tried the move again, then lowered to the stance, shook out both hands, and climbed through to the end of the crack like it was nothing—a yo-yo ascent on the last bit, sure, and some shenanigans pulling up gear, no doubt, but still a complete free ascent of the entire crack. Unfortunately, the anchor was well out of reach from the end of the crack. There was an intermediate bolt between the crack and the anchor, but it could not be clipped from the crack. Lacking a better plan, Alan lunged past it for the anchor sling but missed and fell. He lowered back to the stance, then climbed up and tried again, with the same result.

“If the anchors were a foot lower and to the left, it would be perfect,” he said.

“How about tying a sling to that bolt so you can clip in without lunging?”

I suggested. “Just use that bolt as the anchor for the end of the pitch?”

Alan gave it a gander. “That might work.”

I tied a long sling to the fixed rope and Alan pulled it up, pulled himself up the fixed rope to the anchor, tied the sling to the bolt, then lowered himself back onto the lead rope. I lowered him to the no-hands stance, and after a short rest he climbed through from the stance to the top of the crack, reached up easily to clip a carabiner to the sling, then pulled up a bight of rope and clipped it, and that was that. Alan swung over to the anchor and clipped in, untied my fixed rope and dropped it, and rappelled off using his rope. He pulled his gear but left the two pins he’d fixed in the upper crack, even though he knew they would be gone by morning.

Alan’s repeat ascent of The Stigma had, we hoped, given it an air of legitimacy. It was not a perfect ascent, but it wasn’t bad considering the shenanigans that had preceded. A decade later, no one would have thought twice about lowering the anchors to the top of the crack and calling that the end of the route. In fact, within only a few years, the anchors had been lowered and two bolts had been added to the pitch, a sign that sport climbing had gained a measure of acceptance—even in the Valley. Not only were climbers rappel bolting blank face routes, they were rappel bolting next to perfectly good cracks that had been led free without bolts.

In fact, within only a few years, the anchors had been lowered and two bolts had been added to the pitch, a sign that sport climbing had gained a measure of acceptance—even in the Valley.

But back then, even though Alan’s ascent was done in much better style than Todd’s, it was still considered a travesty by Yosemite climbing mores. Alan’s ascent was instantly discounted by the locals, including the few who had been lurking in the bushes below, watching, eager to report back to the denizens of Camp 4 that Alan had totally hangdogged the route, preplaced gear, pulled up on pins, chiseled holds, and all of that, most of which was entirely untrue.

“So, how hard is it?” I asked Alan as we coiled the ropes and packed our gear for the hike back to the lot.

“I don’t know,” Alan said, looking up at the crack, massaging his aching fingers. “All I can say is, it’s not 5.14.”

By the time we arrived back at the truck, the lurkers were gone but they had left their mark: a cute picture of a doggy drawn in the dust on the rear window, with some censorable commentary about Alan’s sexual orientation.

After a good laugh, we departed the Valley. It had been the shortest, strangest trip to Yosemite I had ever made.

Recent Comments