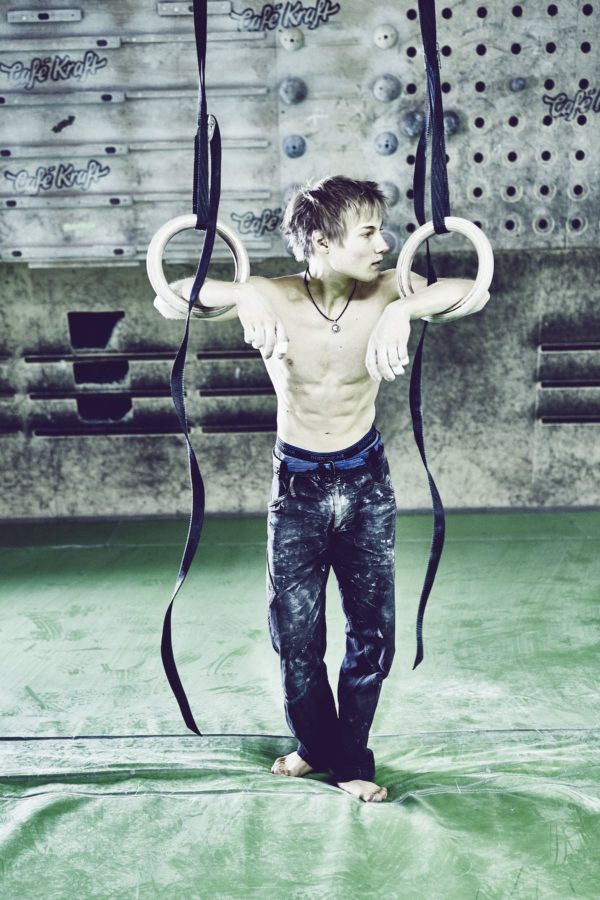

Some of the most famous climbers in the world, such as Lynn Hill, came from gymnastics backgrounds. When I started climbing, I had a high degree of bodyweight strength and conditioning from my time in gymnastics and parkour.

(My approach is detailed in my book “Overcoming Gravity, 2nd Edition.”)

For example, I’ve always been able to do at least 1–4 one-arm chin-ups; dips with at least 90+ pounds for 5 reps; weighted (50% bodyweight) pistols; at least 1–3+ freestanding handstand push-ups; 10+ weighted hanging leg raises, and so on.

You might think this would instantly translate to success on the rock. In fact, I found that my gymnastics background was initially a hindrance, at least during those first few years, because I could muscle through climbs without really learning much technique. That bodyweight strength background got me decently far, however, but I soon stalled out in the V8-10 range.

This led me to experiment over the years, and I have come to some different conclusions on what I recommend to climbers for exercises that are useful for strict improvement.

Climbing is a very skill-based sport, and you get a lot of mileage out of just climbing and learning how to dial in micro-beta and leverage perfect body positions.

However, it is inevitable that weak links may crop up in the chain, whether it is hand strength, arm and body strength, body tension and positioning, or the ability to use leg strength effectively.

This is an overview of how I think climbers should be thinking about incorporating exercises into their training and climbing routines, and what exercises I believe will be most effective for improvement.

Generally, my philosophy is that our weaknesses hold us back more than our strengths can compensate for. I will approach this article from the perspective of working on your weaknesses. You may notice that I am not recommending many of the most common exercises for various reasons.

Assessing Strengths and Weaknesses

On Reddit, Beast Fingers, manufacturer of the Grippul hangboard, posted a study showing a correlation between approximate grip/finger strength to grade level in climbing. Power Company Climbing, Lattice, and others have done similar studies.

According to this data, climbers who can pull 50 percent of their bodyweight on Grippul’s 15-degree crimp can climb V4-V5; 60 percent = V6-V7; 70 percent = V7-V7+; and it goes up to 130 percent = V13-V15.

One must be careful when approaching this data. If your takeaway is that you only need to improve grip strength while lowering body weight to reach your V-goal, you might miss the forest for the trees. Consider how many climbers you have seen who can do multiple one-arm chin-ups, front levers, or have “V10” pulling strength … but end up only climbing V6 in the gym or outside.

Data that correlates something like performance to a grip-strength/bodyweight ratio is interesting, but overly simplistic. The “So, what can you bench?” mindset doesn’t really apply to climbing.

A better mindset for approaching any kind of training for climbing is to begin thinking more clearly about strength and weaknesses. Too many climbers continue only train what they’re good at and avoid tackling their weaknesses.

If you have V10 hand strength but only climb V6-V8, then hand strength is obviously a major strength. It would be ineffective to focus your training on gaining more hand strength, so you should focus on maintaining that strength while targeting your weaknesses—whether it is technique, core tension, body strength, etc.

Similarly, if you have V10 hand strength and climb V9-V11, then this hand strength is neither a strength or a weakness. Focus on improving finger strength during training, but depending on how you do on certain climbs, you may have other more pertinent weaknesses to address as well.

Finally, if you have V10 hand strength and climb V11-13, then it’s likely that hand strength is a weakness. In this scenario, dedicating your focus to improving finger strength would likely be the greatest thing you could do to improve.

This should make intuitive sense to most people, but the data is rarely presented this way. Many climbing articles don’t discuss approaching training with a clear-eyed assessment of one’s strengths, and more importantly, one’s weaknesses.

Leg Strength

It is hard to gauge the effectiveness of leg exercises in climbing because climbing is so dependent on footwork and application of force with body tension.

There are obviously many elite climbers who rarely if ever train legs. However, it is possible that having stronger legs would help climbers step up from compressed hip positions into underlings and other tension-y movements. To assess your leg strength:

If you are able to do 1–2 sets of 10 pistols (single-leg squats) on each leg that is sufficient for all abilities of climbing. This correlate being able to squat similar weights.

Pistols and weighted pistols:

If you have poor body tension—usually emphasized by a sagging core—while applying force through your feet, then common barbell exercises such as squats and deadlifts will be useful … but only up to a point. That point seems to be around 1.5x bodyweight (e.g., you weigh 150 pounds and can squat and deadlift 225 pounds).

The issue I’ve seen with lifts heavier than 1.5x bodyweight is that it can negatively impact recovery to the point where you start having less quality time on the wall.

Some would argue you can work your way up to about 2x bodyweight. Perhaps, but the diminishing gains are probably somewhere in that 1.5x to 2x range.

I personally do not think squats are as beneficial as deadlifts, so I tend to recommend only deadlifts. But if you want to squat, you certainly can.

Bottom line: 1.5x is probably the goal to learn how to generate tension.

If your climbing does not immediately improve as your lifts go up, then your issue is definitely not leg strength. Keep that in mind as you increase the weight and it takes time away from the wall.

Core Strength

I think core has the most overrated and overused exercises. Long routines of crunches, twists, sit-ups, and planks will do virtually nothing to improve your climbing ability.

The problem is, most people do not have a core problem; they have a technique problem.

Improperly turning your hips and not using the right parts of your feet on small footholds may present themselves as signs of a “weak core” when in fact it’s just bad technique. (Perhaps one exception is very tall climbers, who have long lever lengths between hands and feet. In this case, extra core training will help improve your ability to transmit force between your hands and feet.)

Most climbers don’t work the posterior core, which is a mistake since its the posterior core that is especially responsible for keeping the climber on the wall, particularly on steep routes. That ability to drive your hips into the wall, “stay tight,” and keep weight off your arms is largely all posterior core, glutes, and back.

Squats and deadlifts are some of the best ways to strengthen the posterior core. However, if you wanted to work on specific exercises for the back, I recommend reverse hyperextensions. They’re superior for injury prevention compared to back extensions, and you can do them by holding on to a sturdy table or ledge. These can be progressed by holding a dumbbell or weighted backpack between your legs.

Reverse hyperextensions:

I define a weak core as being unable to lift your feet and/or heels above your head easily and apply force in those positions or, or you’re having issues with maintaining tension in stemming positions. If this describes you, then the specific exercises that can be helpful here are hanging leg raises or the ab wheel.

And if you are looking for straight up strength and hypertrophy, weighted decline sit-ups can be useful too.

Hanging leg raises:

A useful progression for hanging leg raises is not just bringing the feet to the bar but bringing them up, out, and away from your hands—up to 2–3 feet away. Put the heel over the bar to simulate a far away heel hook.

Likewise, being able to perform hanging leg raises and then pulling up into the inverted hang position to simulate getting your feet way above your head for a bat hang or hand-foot matches are useful.

Rings

Rings can be used in place of an ab wheel, and make it harder by moving in different directions—not just straight out. You could also use a weight vest or do them off of a single foot, if you need to work on rotational stability.

Hanging leg raises extension to inverted:

Ab wheel:

Rings ab wheel:

Pull Strength

Training strength for pulling is optimal only if there is a weakness. You may often see many climbers training one arm pull-ups and front levers in the gym when they only climb in the V5-V8 range.

Considering that some climbers have gotten to V12+ without being able to do a single one-arm chin-up, it is often the case that strength is not a limiting factor in climbing. If you are pushing into the mid-range of V5-V8+ and can only do fewer than 10 pull-ups, pulling strength is likely a weakness that needs to be addressed.

This is not to say that you shouldn’t do any pulling work. But if training in the gym on pulling exercises is taking away from identifying your weakest links, then you’re going to want to reevaluate your routines. Don’t be the climber whose gym strength is constantly improving all while climbing performance remains plateaued. That means what you are doing is not working.

Here are some ideas, depending on particular weaknesses.

Arched back pull-up:

Wide-grip arched-back chest-to-bar pull-ups are particularly effective for Gastons and wide-span / iron-cross movements. You can improve on it by moving your hands wider and pull your chest to the bar.

Uneven campus pull-ups:

Campus board uneven pull-ups are particularly good for working two things. You can put most of your weight on the top hand for brute strength pulling with a crimp focus which is specific to climbing. Alternatively, you can put more emphasis on the bottom part pulling up into your chest area which is good for working on lock-offs.

Strict bar muscle ups:

Strict muscle ups (rings but preferably bar) can be effective for understanding how to pull strongly into a high lock-off because the transition phase of the muscle-up requires bearing down on the bar and driving the elbows back. This is a very specific strength movement that many below-V8 climbers have difficulty doing effectively.

Explosive bar muscle ups:

Explosive muscle ups (bar) or clapping pull-ups can be useful for generating power if you lack that.

Antagonists (push, push/pull, wrist antagonist)

Antagonist exercises are useful to prevent injury if there are any excessive imbalances. Most sports and disciplines are pushing dominant, but rowing, swimming, and climbing are some of the few that are pulling dominant.

There is no “one good antagonist” exercise that all climbers should do. It depends on your body.

Push-ups, dips, bench press, or overhead press are all fine, if your shoulders respond to them fine. If an exercise aggravates your shoulders even with good form, I suggest removing it and working something else.

Usually 2–3 sets of one antagonist exercise is enough to prevent imbalance. Progressing in strength is good enough, and you do not have to go high repetitions. You can experiment with training 2 exercises if you want as sometimes this can help.

Similarly, wrist extension is one of the most harped upon exercise to improve climbing strength. I can attest that wrist-extension work can be a weakness and improving it can help strongly with pinch climbs in particular. Any of the methods are generally effective: wrist roller, rice bucket, dumbbell wrist curls, and so on.

Find one that you like and progress with it.

Scapular Weakness

Assessing scapular weakness is a bit tough because it’s easily masked by other deficiencies.

I have nothing against hanging shoulder shrugs or one-arm shoulder shrugs building up the weight. These definitely work well if you have problems with scapular depression.

One arm hanging shrugs:

Arched-back front-lever pulls:

The exercise that I have found the most effective is arched-back front-lever pulls. Front-lever scapular pulls don’t focus so much on the front lever portion but on retraction and depression of the scapulas. It’s actually extremely preferable if your back is arched the entire time. I usually terminate sets when it doesn’t get to front-lever height, and I think bent knees are fine, even if you have room for your legs, which I don’t have here.

The front lever is a nice side effect, but remember the focus is on to the scapulas. As the scapular retraction and depression get stronger, you feel much stronger on any movement on the wall. I credit these along with some of the other exercises for much of my outdoor improvement.

Face Pulls FTW

If I had to recommend just one exercise for climbers, it would be face pulls.

This exercise trains scapular retraction and depression, which is good for strong lock-offs; external rotation, which is good for shoulder stability in moves like gastons; and the overall posterior shoulder strength, which helps you understand how to position your body underneath your hands better on overhangs.

Face Pulls on Rings:

Face Pulls on Cables:

Finger Strength:

We’ve all been told that hangboarding is the best “bang for your buck” exercise you can do as a climber. Hangboarding, campus boarding, no-hang devices, and other such tools can be useful if you have weak or average finger strength.

I personally like hangboard, no-hang devices, and finger rolls. I don’t necessarily think one type if superior to the other, so experiment with them and see what you like better.

That said, I see most climbers spending too much time focusing on finger strength off the wall at the expense of using their time to, say, hone their technique through actual climbing. And besides, actual climbing builds finger strength along the way really well anyway!

If you believe you have a deficit in finger strength, my recommendation is not to hangboard more, but to find climbs that work your weaknesses.

For instance, find a couple of climbs that seem to target the type of finger strength you need to improve on (crimps, open-hand, pinches, or pockets, etc.). Practice these for 3–5 times each to start, then building up to doing them 5–10 times over the course of a week.

After a month of this, you should notice weekly improvements in your quality of movement on the climbs and your ability to hold on to the climbs better. These things do not have to be high volume to improve on.

One of the most underrated tools for improving finger strength is simply traversing a lot in a gym. Some would say it works endurance much more than hand strength, but there is a big overlap between both because in the long run forearm hypertrophy correlates strongly with strength. Note that most world class boulderers climbing V14 can also send 5.14-5.15.

Routines and Increasing Volume

Generally, I’m a big fan of the 80/20 rule, where 80% of your time is spent climbing and the other 20% is spent training.

For beginners, that ratio ought to be closer to 90/10 or even just 100 percent climbing. If you’re climbing 3 times a week for a couple hours each (minus warm-ups), you should be doing no more than 30 minutes of training in the gym each session.

There’s a tendency to add too much frequency too rapidly. Go slow. If you want to climb 4–5 times per week, start off at half that and build up slowly. For instance, let’s say you’re climbing 3x a week for 2 hours. This is 6 hours of total volume.

If you want to bump that up to 4x a week, the best thing you can do is keep volume the same—i.e., make each session 1.5 hours instead of 2. Increases of volume of more than 30 percent are generally correlated to increasing overuse injuries.

Keep the sessions at 4x 1.5 hours for a few weeks and see how you do. If you’re doing fine and there’s no evidence of overuse injuries popping up such as painful joints or inflamed connective tissues or tendons, then go ahead and make one of your four sessions 2 hours long.

If this seems painfully slow … that’s the point. This gradual method allows the body to adapt to increased work capacity as you get stronger.

That said, more is not always better. If you’re going longer but the quality of the sessions starts to decrease, you may want to cut back. This can happen for any number of reasons such as decreased sleep, poor nutrition, and stress from life. Scale down if life is getting in the way.

This is how pros like Adam Ondra can build up to climbing 4–6x per week for multiple sessions a day without destroying their bodies. A beginner who attempted this schedule would rapidly get injured. Go slow and remember that, after all, climbing is a lifelong game.

Pulling it all together:

Here’s a general hierarchy of specific things you want to do before defaulting to gym exercises:

- Focus on working on your weaknesses above all else as your climbing is generally only as strong as your weakest link.

- Try to work your weaknesses on the wall before hang boarding, doing pull-ups, and other specific training exercises. Select climbs that challenge specific weaknesses in your finger strength. Climbs that require an explosive pull or strict lock-off are better than doing those kinds of exercises in the gym.

- If you really must train in the gym, find the exercises that will work your weaknesses.

Here are some of the general exercises I’ve come to understand are some of the most effective at improving particular climbing weaknesses.

Legs:

- 1–2sets of 10 reps pistols are sufficient for leg strength.

- Squat and deadlifts if you have poor tension up to about 1.5x bodyweight are more than enough.

Core:

- 1–2sets of 20–30 reps of weighted reverse hyperextensions.

- 5–10reps of ab wheel or hanging leg raises.

Pull:

- Super wide-grip arched back chest to bar pull-ups.

- Alternative is campus board uneven pull-ups focusing on the top or bottom arm depending on if you want lock off or pull strength.

- Strict or explosive muscle ups can be effective for transition and powerful pulling respectively

Push/pull:

- Anything that doesn’t bother your shoulders.

- Alternatively, if you do muscle ups they can double as the dip portion.

- If you need wrist strength, wrist roller, rice bucket, DB wrist extension all work.

Scapular strength:

- Arched back front lever pulls

All-in-one:

- Face pulls

Fingers:

- Just go climbing, especially on climbs that challenge your finger weaknesses.

- If you need to do some exercises to bring up the weaknesses, finger rolls, hangboard, or no hangs can work.

My personal routine

Personally, I mainly do rings face pulls and maybe a couple other exercises depending on my weaknesses while maintaining my strength with many of these with just 1 set of exercises a couple times per week. This takes about 15–20 minutes and leaves a lot of time for me to focus on honing climbing technique.

- 1 set of ab wheel.

- 1 set of reverse hypers.

- 1 set of dips.

- Traversing and finding climbs I am weak on or hangboard/no hangs.

- 1 set of DB wrist extension.

- 1 set of pistols and maybe a 1–2 sets of muscle ups.

About the author:

Steven Low is a former gymnast, coach, and the author of the Overcoming Gravity: A Systematic Approach to Gymnastics and Bodyweight Strength (Second Edition) and Overcoming Poor Posture, and Overcoming Tendonitis. He has spent thousands of hours independently researching the scientific foundations of health, fitness and nutrition. His unique knowledge base enables him to offer numerous insights into practical care for performance and injuries.

Steven’s feats of strength include: full-back lever, full front lever, four strict one-arm chin-ups on both arms (eight on each arm alternating), ten-second iron cross, straddle planche on rings, five reps of +190-lbs. dips, +130-lbs pull-ups, +70-lbs strict muscle-up on rings, a single ring muscle-up, eight freestanding handstand push-ups on parallettes, five rings hollow back presses, and twenty degrees off full manna. He is currently working on applying his efforts to achieving high level bouldering and has achieved several V10s.

You can find his training, injury, and climbing articles at http://stevenlow.org/

”If you are able to do 1–2 sets of 10 pistols (single-leg squats) on each leg that is sufficient for all abilities of climbing.”

A set of 10 pistol squat ?? That a huge amount of legs strength. Not sure.

Except this, everything you said is very clear and well said.