Dave Hume is a mythical figure at the Red River Gorge, renowned, revered and whispered about to this day for his legendary crimping power and eye for the most plumb lines. Back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Hume cherry-picked some of the best, most beautiful routes in the Gorge. His routes included some of the stiffest, like the ultra thin Thanatopsis or notoriously sandbagged Nagypapa. No matter what the route was rated, it seems like every route he established holds its status, even to this day, as a classic testpiece.

Hume established True Love in 2001. Located just right of the now hyper-classic Golden Boy at the Gold Coast, this 65-foot, six-bolt “crimping testpiece” was being brushed and bolted right around the same time my brother was teaching me what a crimper was on the recreation center’s climbing wall at the university we both attended. Meanwhile, Hume (along with other locals) were setting new standards yet to be seen in the area. This was the early turn-of-the-century explosion of development in the Red River Gorge—a time when route development exponentially outpaced guidebook production. Sport climbing was “in” in America. And the endless swath of blank, bolt-less rock in the Red River Gorge was where it was at.

But compared to the scene today, the Red back then was slower, different. The Petzl RocTrip hadn’t taken place.

There were no lines five-deep for Golden Boy or Flour Power or Chainsaw Massacre. And every man, woman and child hadn’t yet sent God’s Own Stone.

The Chocolate Factory wasn’t in production, churning out routes by the dozen, and Pure Imagination was still a figment of our, well, imaginations.

My group of friends included “the Jens”: Jen Vennon (now Jen Bisharat) and Jen Sauer; John Shrader, Kenny Barker and the infamous vodka-swilling philosopher Bill Ramsey. We would spend our summer days sweating it out at the crag, swimming in the reservoir, or playing video games in Kenny’s camper.

Miguel’s was desolate during the weekdays, and the campground in the back was 1/8th the size it is today. You knew everyone that walked through the doors and what they were projecting.

It was a small tribe, but a tight one.

Back in 2003, when I first started climbing in the Red, there were far less climbers—but even more noticeably, there were far less women climbers. You could probably count all of them on a hand or two.

When I first started climbing with this group, I watched and learned from Jen Vennon who, at the time, was the strongest, most badass female climber I knew.

It’s really inspiring seeing other females climbing strong, confidently and proficiently. I was awed by Jen’s ability to hold on for just about an eternity and slowly but surely lock off her way up some of the Red’s hardest routes.

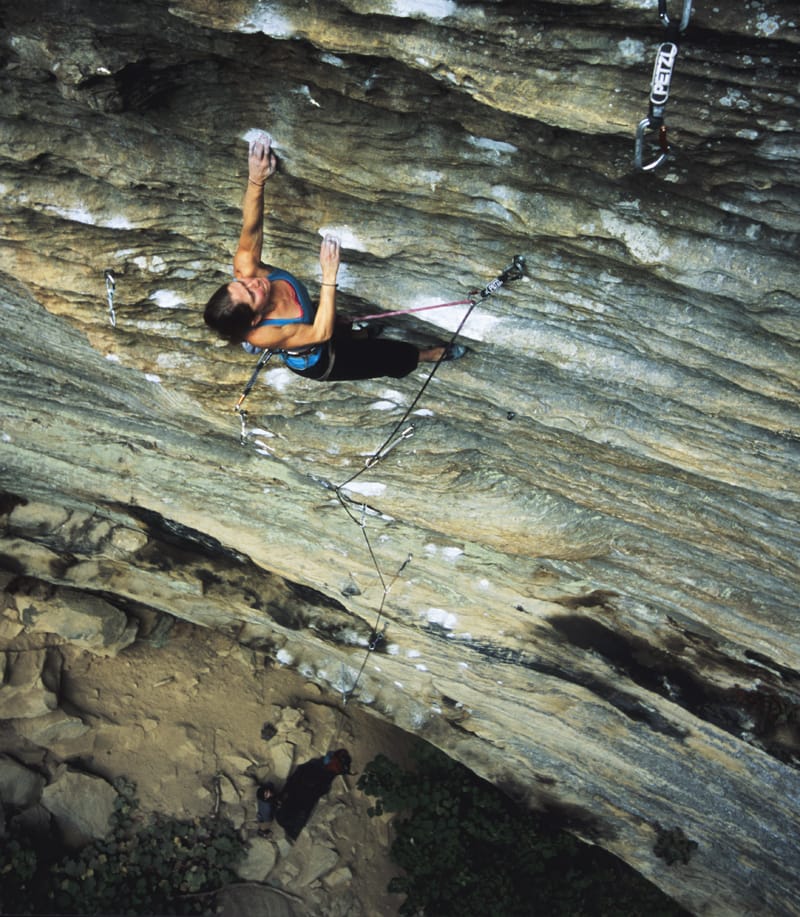

Prior to Jen’s arrival in the Red, Katie Brown was the female empress of climbing here. Back in the 1990s, the concept of a “first female ascent” held a lot of clout within the imaginations of climbers around the country, especially in the Red. Katie tore through the classic routes here, even onsighting Omaha Beach—a route that got the swift downgrade from 5.14a to 5.13d the moment she clipped the chains (though it was again upgraded when a hold broke a few years later). Her impact on the area was so influential that a super-reach-dependent route was even named “Take That, Katie Brown”. It was a way to poke fun that there was at least one climb that she wouldn’t just easily onsight.

As a couple of female climbers in the Red back in 2003, Jen and I were very aware about which routes Katie had climbed, and which routes were still awaiting first female ascents.

Soon, I progressed in my own climbing to begin climbing with Jen on the same projects as her (rather than just projecting her warm-ups). We ticked classics, tried increasingly harder routes and repeated a lot of what Katie Brown had done in her brief but glorious stint here as a teenage phenom.

But again, this was a period of rapid development. Entire sick new walls were being discovered each season. So Jen and I started trying these new rock climbs. And because there simply weren’t that many other female climbers trying these routes, by default we got to claim our own first female ascents.

Elephant Man, Darth Moll, White Man’s Shuffle, Paradise Lost, Dracula ‘04 — it was either Jen or myself claiming an FFA.

To be perfectly honest, this was a really fun, motivating and exhilarating game. People were paying attention to us, too. We were seen, I guess, as an anomaly in those days. And that felt kinda cool. At the time, being the first female to climb a route in the Red still felt very notable in the wake of Katie Brown—but also in part because female climbers were still rare. You could practically eat dinner at one table in Miguel’s with most of them.

But the other part of it had to do with the fact that there was a legitimately pervasive culture of good ol’ boys hanging around the crags. Jen Vennon, Jen Sauer and I were all routinely forced to kindly diffuse the question of yet another concerned male: “Can I set up a top-rope for you on this 5.9?”

We’d have fun with that poor boy, too. We’d bring him out to the crag, his hopes high that he’d get to impress three girls with his climbing abilities all day. Maybe he even thought he’d get laid that night.

Then we’d blindside him by casually warming up on a 5.12. His face would turn red as he backtracked to find some reason why he’d just try it on top-rope. Then we’d snicker to ourselves as he’d be pumped and hanging by the fourth bolt.

Years passed and my core group of friends all moved away. Times changed. Climbing as a sport changed. Our group of friends would see each other in various spots across the country, but never together in the Red like before. Those early days were times I cherished and remembered every time I visited the Red, which I still try to do at least once a year.

While I had known about True Love for years and remember it from these early days, I never actually tried it until the fall of 2010 during one of my return trips. At the time, I was living in Chattanooga and had come to the Red in October.

I was looking for a project and one day I walked over to the Gold Coast to belay a friend. I considered jumping on God’s Own Stone, but there was a line five-deep. I watched the incredibly strong and mild-mannered visiting pro Paige Classen work her way through the moves on God’s Own Stone, which she ultimately sent for its first female ascent.

But instead of joining in on the action, I decided I’d have a better time on a less-occupied climb.

I had been drooling over True Love for years, but had been too intimidated by its reputation of being nails hard, elusive and rarely climbed. I remembered watching Kenny Barker on it years earlier. Over and over, he would get to the middle of the crux and, for seemingly no reason at all, come ripping off in a slow-motion arc. When he hit the end of the rope, in his classic way, Kenny would simply yell: “Did you see that? I almost had it!”

But rarely, if ever, did I see other climbers working on it.

True Love is “only” 5.13d but far cruxier than its neighboring route, God’s Own Stone, which gets 5.14a. Those two factors have combined to make True Love an overlooked climb.

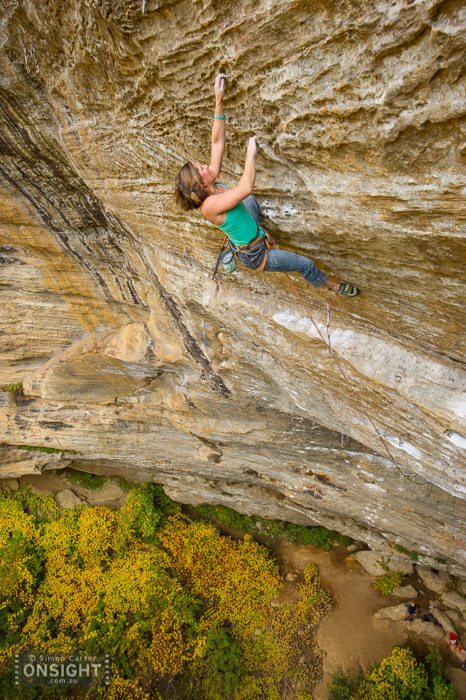

True Love starts with three bolts of straightforward 5.12c crimping. You get a mildly good, finger-bucket to cop a shake, then you launch into the one-bolt, finicky V9 crux before ending with two additional bolts of 5.11.

I figured out desperate beta through the crux. And I sussed the top. After a few more days of work I whittled it down to a solid one-hang, but the crux was low percentage. The more lightly I grabbed the holds and more fluidly I did the movement the better, but those two things often evaded me. The less secure I felt on the holds, the tighter I gripped, and the climb unraveled from there.

Originally, I was trying the crux by desperately thrutching to a tiny pebble with my index finger and stacking the rest of my fingers on top, in a neat little pile like pancakes. Then, I’d launch to the “brick” hold where I clipped the draw. This was OK for a single effort or two, but any more and I’d rip a hole in my finger. I fell repeatedly trying to grab this hold with my index finger—tearing skin and getting more and more frustrated with how low percentage the move was.

I’d spent at least two weeks of my month-long trip getting to this move only to tear my skin. The move was getting really mental. I was afraid of it. Dreaded it. Would I ever stick it? Having still not stuck the move from the ground, I wasn’t sure if this route would ever go.

Until one day I stuck the pesky little nub from the ground.

The conditions were amazing: bluebird skies with the perfect combination of dryness and humidity.

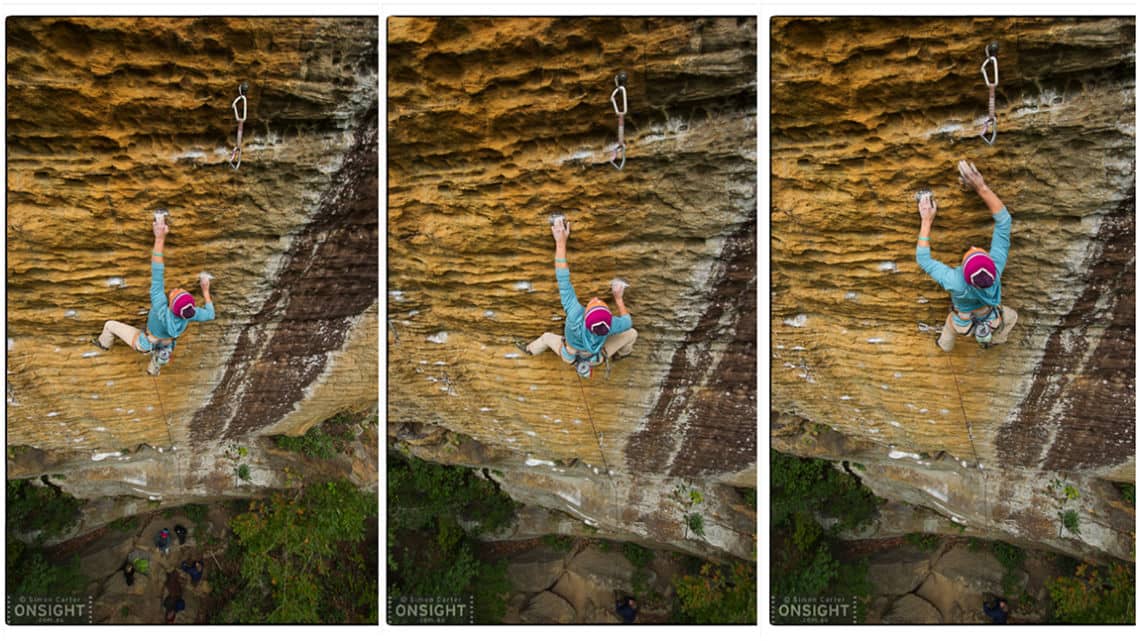

When I finally stuck this pebble, I gasped—almost squeaked with excitement. The pebble was digging in, and as I moved my feet, it punched through my skin like your front tooth into an apple. But because I was still on the wall, I just hucked for the brick. My legs and arms swung wildly. And then, just like I remember Kenny doing, I came flying off the route in a perfect arc.

Shitty weather, as it’s prone to do in the Red, set in for days. The end of my trip was approaching in two days, and I got anxious. Then, a freak spell of amazing weather tore into the Red like it had been sent by the gods. Cold air sucked all the humidity away and it was fully fall weather, the kind that turns sandstone fly-paper sticky and just grabs every ripple of your skin. These are the days we wait for all year, the best days.

I returned that first good day with renewed psyched and fresh skin. But once on the climb, my head came back into play. I was over-thinking and dissecting beta into oblivion, as I tend to do when I want to send something really badly. Frustration was high, focus was low and anxiety off the charts.

I decided to try something different. I don’t know why. It was one of those inspired moments when a fresh idea comes to you out of nowhere and you don’t know why. I realized, by sheer chance, that if I shoot for the pebble with my pinkie instead of my index finger, the rest of my fingers would kind of settle on the slightest curvature on the wall and somehow, like magic, stick.

Now it was on!

The next day I warmed up and waited for the most perfect temps, which occurred right as the route went into the sun at 2:15 p.m. From 2:15 to 2:20, there was a five-minute span of time when the rock would be warm enough to not numb out, cold enough to remain sticky, and, essentially, just perfect.

As I started to climb I felt a little shaky and cold. But the sun started to peak around the rock and warmed me up enough to continue on. I arrived at the crux feeling good and hit every move perfectly. I used my new pinkie-on-the-pebble approach, and my other fingers seemed to stick into the slightest vertical nothingness like spider legs. I put my right foot on, dropped my left and floated—like a puff of chalk, I swear —up to the brick.

“Holy shit, I might be able to do this thing! This might even be a first female ascent,” I thought, chuckling.

I was making the ultimate sport-climbing mistake: thinking about the anchors before I was there.

I shook out on the brick and hastily climbed into the next section of 5.11. The moment seemed primed with feelings of personal greatness. Then two casual moves in, a ray of sunlight stabbed me directly in the eye.

The rock didn’t look the same anymore! I could hardly see! It was all just a blinding swath of fuzzy-looking holds. My brain was being overloaded. I overgripped the mildly chalked, slopey holds and suddenly found myself fighting to stay on. I was grasping at any ripple in the wall that looked like a hold. Panicked, I started paddling through unapproved beta. But by then, it was too late. I was off. Outta there. A goner.

I hit the end of the rope, reached down, and took off my left shoe. With great force and precise trajectory, I launched my shoe as hard as I could into the woods.

I had wanted the send. Maybe, in the back of my mind, I’d wanted to relive those days of getting another first female ascent in my old stomping grounds. I’d wanted it so bad that I’d let the route and my failure cause me to actually throw my climbing shoe into the woods. The WOODS!

I left that day to return home—dejected, humbled, let down and totally embarrassed.

It was another year before I returned to the Red. A lot can change in a year. I am, I’ll be the first to admit, a little obsessive when it comes to redpointing. I get sucked in. Maybe part of it is just who I am, but part of it is also deeply engrained from 14 years as a competitive gymnast. It’s been beaten into my head that “practice makes perfect.” Whittling down a route to perfection comes as second nature.

But more accurately perfect practice makes perfect, endlessly throwing yourself at a piece of rock doesn’t always make perfect.

Time, distance, and perspective, for me, can go a long way in climbing. When I get so sucked into doing a route, I can forget what I really love about the route, and climbing, in the first place: the inspiration, discovery and intricacies such as figuring out pinkie beta or the exact five-minute time frame when the route feels perfect. Then there’s all the connections, bonds and friendships (like the Jens) I’ve made and continue to make through climbing.

The desire to succeed can make you pretty stupid sometimes. It can make you forget to appreciate how all the things and people that you love are brought together in so many unexpected ways in communities like the Red.

When I returned to True Love a year later, I no longer needed to send. I was happy to return to it despite the outcome. Just a visit to an old friend.

Sure enough, I sent second go. It was strangely anti-climactic. I might have been the first female, but I also might not have been. I honestly don’t know and don’t care anymore. What I did realize was how much I love climbing. To be consumed by passion for climbing—for anything—made me feel truly lucky. As Russ Clune once said, “We are in the one percentile of the one percentile of people that have found something to be passionate about.”

We all strive towards and treasure the days we send, but what’s interesting and also counter-intuitive is that climbing is mostly about the days we don’t send. It’s about all those shoe-throwing, ego-filled days leading up to that fleeting moment of success. Maybe that’s what makes it all worth it. You have to learn, over and over, to let all that stupid stuff go and remember to appreciate that you are getting to do what you truly love.

0 Comments