It’s been about six years since I sent Flight of the Challenger—a 5.12 (12b? 12c?) trad climb at Squamish. It says a lot that I don’t remember the things you’re supposed to remember—like the route’s grade. I vaguely recall an uninspiring peg at the start, and a crazy, technical groove at the top. What I remember most about this trad climb was what it taught me about my ego, my gender and my confidence.

I remember Flight of the Challenger as a route that taught me some important things about what it means to be a female climber.

I was 19 and on my “gap year.” If you’re not familiar with the term, enlighten yourself by searching “gap yah” on YouTube. It’s a year taken out of education between school and University where young British teenagers go traveling to discover things about the world and themselves. If you watch the video, you’ll see that many Brits have taken the idea too far—or not far enough, depending on how you look at it.

I had taken it pretty far. I’d been to India, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, China, Australia, New Zealand, and the USA, where I had my first taste of granite crack climbing in Yosemite during the heat of August.

I started climbing when I was 7 and had amassed the requisite face-climbing skills to avoid most cracks in the U.K. Any cracks I’d previously encountered I’d been careful to navigate my way around them.

But here in Yosemite, I couldn’t climb 5.8 cracks without shouting, swearing, sweating and generally having a terrible time. Climbing was something that I was always naturally good at. It was a horrible feeling; to have that thing that you’ve always been so naturally good at, become a thing that is not natural, and not something you’re good at.

I remember looking up at El Cap and decided that only a miracle would ever get me up that thing.

We hitched to Squamish the next day, and I spent the remainder of the summer gaining an education in granite climbing, becoming better at it each day. Soon, I had bouldered my hardest problem (a V6 whose name I can’t remember), onsighted a 5.12a (Sentry Box), and then onsighted a 5.12b trad route at Murin Park.

At night, I camped under the Chief. What route I was going to climb the next day was my only concern in life. I was learning a lot about myself, as I imagined I would on my gap year. Yet part of me recognized that soon I would have to go home and take my place at Bristol University. I intended to get a degree in Philosophy and then do a conversion course into Law. I thought I wanted to be a career women like my mum. But I’m the spawn of my Mum and my Dad and here in Squamish, I tasted what it would be like to lead the life of a full-time climber. And I liked it.

As I was traveling alone, I was always looking for partners and jumped at every opportunity to climb with newfound friends. I met Sean Villanueva O’Driscoll in the boulders playing a flute. I liked him immediately despite his terrible flute playing (I think he may have improved since). I met Nelly Milfield in the Chief campsite and I liked her immediately, too, despite the fact that she was a lawyer and had an outrageous laugh. One day Nelly, Sean and I decided to spend the day cragging at Murrin Park, an excellent collection of granite cliffs south of Squamish.

Sean casually onsighted Flight of the Challenger and I let him know that I wanted to try it, too. Being a British trad climber raised by my trad-climbing dad, I had only ever climbed trad routes onsight—meaning, ground-up. No top-roping. I had never even considered top-roping a route first.

Although Sean had made Flight of the Challenger look easy, the route also looked a little scary so I expressed a few concerns.

“Is that peg any good?” I asked Sean. “If I fall just above it, do you think I would hit the ground?”

Sean looked shocked and said, “No of course not, I’ll keep the rope tight. … Don’t worry! You’ll just swing out a bit. The ground drops away.”

At first I thought he was a bit dumb—or I was just confused.

Then it dawned on me that Sean was assuming I was going to top-rope the route, not lead it.

I told him that it hadn’t occurred to me to top-rope the route and that actually I wanted to lead it. “No I meant, if I was leading it… Do you think that’s a bad idea?” He seemed very surprised.

I knew he was a good climber and I started to second-guess my chances on the route. Maybe this route was a death route. Either way, the look of concern on his face was enough to put me off leading it, and I tied into the blunt end.

I climbed the route on toprope with no falls. Two days later I came back with Nelly and led the route clean first try.

Although I was psyched to send my hardest route, I was annoyed that I had been discouraged from trying to flash it. Of course, it wasn’t Sean’s fault; it was my fault.

The reason this send was so important to me wasn’t because I don’t believe in rehearsing routes first. It isn’t even to do with what male climbers expect from the average girl at the crag.

It has to do with self-belief. I know how well I can climb a lot better than a random guy I met two days ago. So why did I trust his judgment and not my own?

Fast forward three years. I finished my degree in Philosophy and started my life as a full-time climber sponsored by The North Face. Upon graduating, I spent the first two months of summer sport climbing in Ceuse, then alpine climbing in Chamonix. By September, the names Kant, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche had all but faded from my mind and were replaced with an all-consuming dream of returning to Yosemite and free climbing El Capitan: the very thing that, years earlier, I told myself I would need a miracle to ever do.

By October 2011, I was standing beneath the 1,000-meter walls of El Cap next to my friend Hansjorg Auer. We had spent some time climbing together in Rodellar earlier in the year, and had made plans to meet in the Valley in October to team up and give El Cap a shot.

Freeing El Cap is something most climbers want to do when they get to a certain level. The beauty, history, height and hard nature of the climbing make freeing El Cap an ultimate climbing goal. There’s nothing else like it.

Lynn Hill’s groundbreaking first free ascent of the Nose adds another special and important layer for female climbers—or at least it did for me. Hill’s accomplishment not only changed the perceptions of what women were capable of achieving in the climbing world, but she actually pushed the sport of climbing forward by leaps and bounds.

Ever since my first trip to Yosemite, when I found myself screaming up 5.8 hand cracks, I knew I wanted to return. And I knew I wanted to climb a free route on El Cap.

For a long time I didn’t have a partner or a route in mind. I wasn’t particularly drawn to Free Rider, the usual goal for most aspiring El Cap free climbers. I had seen pictures of Golden Gate, originally freed by the Huber brothers in 2000 at 5.13b and 41 pitches long. Seeing photos of those beautiful golden walls with perfect granite edges cemented in my mind that Golden Gate was the route I wanted to try.

I spent some time wandering around Camp 4 asking for beta for Golden Gate. It was a very discouraging afternoon.

“Don’t you know Golden Gate is supposed to be very reachy? The 5.13 ‘Move Pitch’ will shut you down if you can’t reach the holds!”

“Martina Cufar flashed the ‘A5 Traverse,’ but couldn’t do the ‘Move Pitch,’ or the ‘Down Climb.’ Too reachy!”

“I heard small people have to enter the Monster offwidth in a different way!”

“What’s that? You’ve never even climbed an offwidth!”

“Wait, you’ve never even climbed EL CAP!?!?!”

I was all but laughed at just for mentioning Golden Gate. I felt ridiculous. I couldn’t blame them, either. Who was I to try and free climb El Cap? I hadn’t even aid climbed a big wall before! Staring up at the Big Stone I felt unable to even aid up the thing let alone free climb it. I’d never hauled, never slept on a portaledge, never known how much water you need for 4 days of climbing. So I knew that free climbing Golden Gate on my first attempt at big walling might be too much to ask. I wondered if I should shift my focus to Free Rider, a route other women had done and was considered easier. Why had I chosen the route that women had failed on?

My friend Mayan Smith-Gobat said something to me that really stuck.

“There are tons of question marks for you on this route. You just have to go and try. It will be a great experience whatever happens.”

I remembered the day at Murrin Park, when I had trusted the judgement of others before my own. I didn’t want to let that happen again. Mayan was right. Why not just try?

Trad climbing is intimidating in general—but it gets much worse when you let the monster grow inside your head, and become super scary way before you even tie in.

A wise boy I used to spend a lot of time with would often say, “We’ll just take the gear for a walk.” To imagine free climbing El Cap, with all those hard pitches and all those question marks stacked on top of one another, is just too much.

But to pack the bags and drag them to the bottom of the cliff … well, I can do that.

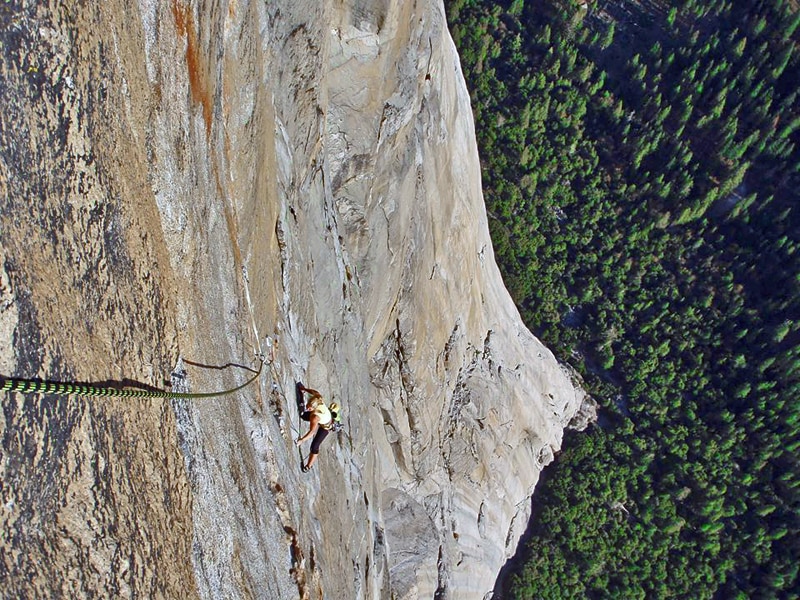

As soon as Hansjorg arrived in the Valley, we were off. On that first day, I grew worried that I was too incompetent for a route like this. I managed to haul the first pitch, but only just. It had taken everything for me to get the bag up one pitch. I looked up: 38 pitches of steep granite loomed above me. Maybe I should just concentrate on getting to the top in one piece! We stashed our haul bags on Heart Ledge, and came down.

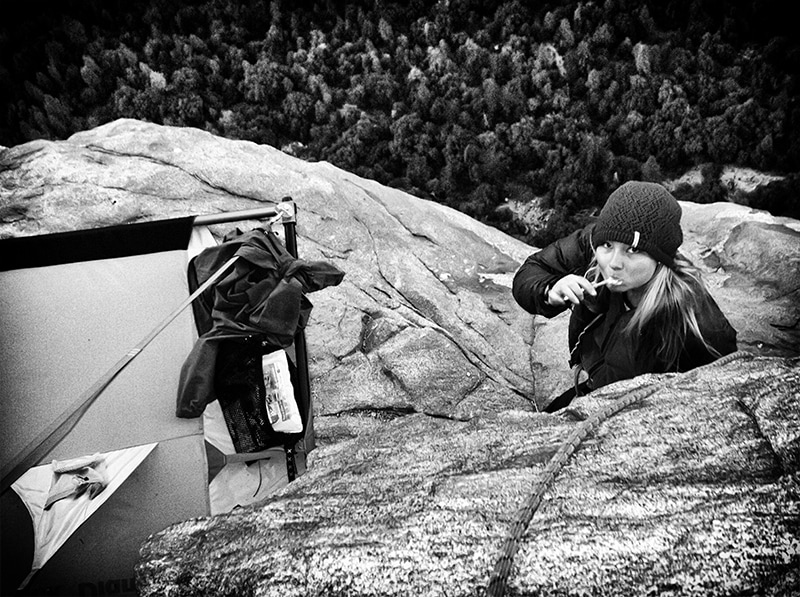

The morning we set off for our push, we climbed the Freeblast just as light was hitting the wall and reached our haul bags in not much time at all. I felt a little bit of confidence creep in. We climbed and hauled to beneath the Ear and set up the portaledge. The day was hot, long and hard, but we had already climbed 19 pitches. However, I knew that next morning Hans and I would be facing what we both feared most: the Monster Offwidth.

Hans insisted he lead it. I didn’t really care—I knew I would be fighting either way. That morning, Hans set off and climbed really well, making a lot of progress, and clearly giving it his all. Then a few meters from the top, he slipped out. Exhausted, he got back on and went to the top. Now it was my turn and I was shocked at how nervous I was. I did the big move into the crack, which was something I was worried I couldn’t do. The first half went well, and I began to feel increasingly cocky about doing the pitch.

Then for some reason it became harder and harder. Scraping my feet around to find a good heel toe and jamming my head against my hand in the crack, I found myself doing everything I could to stay in. Fortunately, I didn’t fall, and arrived at the belay to find Hans equally exhausted. I asked if he wanted to go again, and he shook his head. With barely any skin left on his ankles, knees and elbows I knew that he had given everything. He took this with great acceptance, which, looking back, is something I really admire. I turned my attention to the next set of pitches leading to the next big question mark: the infamously reachy Down Climb.

Hans went first and to my disappointment agreed that it was reachy. My first try was in the hot sun and just by looking at how far apart the holds were, I decided that Hans’ beta would not work for me. But later in the evening when things had cooled off, I tried the move again and surprised myself by how close I got to doing it. This could actually be possible for us and hope started to creep in.

Working out these technical slab moves was so much fun in comparison to all the burlier pitches below. Over 20 pitches up the side of El Cap, there I was, attempting a wild foot-hand match to a downwards mantel. This was so cool!

We called it a day and spent the night in the portaledge. In the cool shade of the next morning, we felt even more hopeful that we would do it. We both got it really quickly. Weirdly enough, our beta had been almost identical—despite the fact that I’m only 5’2” and Hans is more like 6’2”! Although we cheered at our success, just as quickly my thoughts turned to the next big question mark: the dreaded ‘Move’ pitch a couple of hundred feet up.

Half of me was full of hope: if the Down Climb is possible, maybe the Move is, too. We kept climbing toward this big unknown. We arrived to find Luca, our Slovenian friend, trying the Move Pitch.

“I’m too short to do this Move!” he shouted down to us. “Unfuckingbelievable!”

He had freed everything so far and was clearly pissed off about having to jump to a two-finger pocket instead of simply reaching. Being quite a bit shorter and most probably weaker than Luca, I quietly scolded myself for being so naive as to think that I could do it.

Hans led up and impressively got the Move second try. But Hansjorg is quite tall and very strong, so this did not inspire me in the slightest.

My turn. I climbed the lower section of 5.12a and reached the undercut from which you do the Move. I looked up. The next hold was farther away than the entire length of my body! But in the flow of the climbing I saw a faint sloper in between the two holds. I could only hold it with my right and if I got my left foot really high. But I could not match the sloper. This meant that instead of reaching the next hold as a sidepull, I was forced to do a huge cross over with my left hand and take the side pull as a gaston. But this beta kinda fucked me because the next hold was up and left and I was wrong-handed. I fell off exasperated and disappointed. I played on the move for a while, trying all sorts of different things. Jumping didn’t work because the hold was side pull. I pawed around on all the other features in the rock, willing myself to be able to hold them, but couldn’t.

I strained my brain trying to think of how I could do this section … There must be a way. After trying everything I could think of, I knew that the closest I had come was on my first attempt with the crazy cross-over. All I had to do was work out how to get my right hand on the hold instead of my left.

It sort of dawned on me that I would have to match this horrible gaston and make it a side pull. But with no feet out right I wondered whether I would be strong enough. After a few attempts I had reached a point where, I could kick my right foot up on a smear and, in a back-contorting position, ultimately match the hold. Then the next move—reaching the pocket—involved being completely stretched out in a totally off-balance position with foot movements that felt crazy hard.

As I swung around with a thousand feet of air beneath me, I thought to myself that if this were a boulder problem on the ground I would be really pleased to do it. But I had done the move so, theoretically, I could do the pitch. By this time the sun had arrived. My skin was shedding by the second. I came down and asked Hansjorg if he wouldn’t mind waiting for the morning shade.

The next day I woke up, really nervous. I knew I could do it, but I felt tired, achey and my back was stiff. Just before I started climbing, I heard a succession of congratulatory cheering coming from around the corner to the left. Clearly some other climbers were dispatching the crux pitch of Free Rider. After four cheers, I thought, “Come on, Hazel. They are sending, now you have to, too.”

With no warm up, I felt really shaky on the start. I also felt the momentousness of the pitch. I realized that if I didn’t get it this morning, with only a certain amount of food and water, we would be forced to move on. I had to do it now.

“Come on Hazel, you can do it” Hansjorg shouted. I pulled into the move, crossed over, and tenuously hopped my right foot up a succession of miserable smears into a position that allowed me to match. Trying my best to trust my right foot, I came in to the match and reached across. I was into the pocket! With a few more hard, pumpy moves to go I prayed that I could compose myself enough to do them. With Hansjorg, Luca, his partner, Nastia, and another French team all cheering, I reached the finishing jugs, really relieved.

I know I have described this Move—or, four moves, in my case—in a lot of detail. But this was a crux unlike I have ever done. In all those hundreds of feet of climb, this 10 foot piece of golden, pocketed rock, had forced me find a self-belief and creativity of movement that I would not have thought possible for me.

This is the beauty of facing question marks—like Mayan had said. Sometimes you might get shut down. But you never know what you’re going to find until you try.

A few more pitches took us to the Tower of the People, where Luca, Nastia and the French team were all resting in their ledges. In the evening light, Hansjorg and I both flashed the Desert Gold, a beautiful golden 13a pitch. After which, we had an unsettling moment where Hansjorg took me off belay and it took us 15 minutes to realize I was sitting on the portaledge, not clipped in to anything (!). Obviously we were getting too comfortable on the wall. I was really just pleased to have knocked off two question marks in a day, and to see some friendly faces. I enjoyed an evening sharing our experiences of the route so far.

The next morning Hans impressively onsighted the 5.13a “A5 Traverse” with no warm up. Although he proclaimed it easy I was feeling pretty doubtful. Four days on the wall had caught up with me and a pumpy traverse on slopers with no feet was not my style. I gave it a bash and fell pretty early on. Panic crept in. I knew Hans wanted to finish the route today and I knew that I had only an hour or so before the sun came on to the wall. I had a hurried rest and tried again. The next time I gave it my all but my foot popped off a heel hook a few feet from the belay. A little heartbroken I almost lost my composure. I had been so excited to do the Move Pitch and now it seemed like a free ascent of El Cap was slipping away. Hansjorg remained super chill and encouraged me

“Hazel, this is just a short traverse,” he said. “Just rest and try again. No big deal, come on!”

On my last go, knowing the moves better I climbed quickly to make up for my fatigue and arrived at the belay very relieved. With only four more easier pitches to go, I knew I would free climb El Cap.

Despite all the question marks, I managed to free Golden Gate. Yes it was by the skin of my teeth. Yes I needed to be babied up the wall by Hansjorg. But I did it.

On the way down to Camp 4 from the top of El Cap, I thought back to that day at Murin Park, after sending Flight of the Challenger. In the three years that had passed since that day with Sean and Nelly, I had learned a lot—but here in Yosemite, I had still doubted myself. I still almost didn’t try Golden Gate.

I’m still learning the mental games of climbing and what I’m slowly beginning to realize is that it’s better not to think about whether you’re a good climber or a bad one, or whether you’re better or worse, or stronger than the next person. It’s just about trying—and trusting yourself.

If being a full-time climber was what I wanted to do, I had to try. If freeing El Cap was what I wanted to do, I had to try.

If you forget about the question marks and just take the gear for a walk, you’ll have an experience, some kind of experience, and that’s what climbing is all about.

Inspiring and thoughtful – thank you

Thanks for the motivating read Hazel!

Impressive and very inspiring! Follow your own way and don’t give up, then you’ll meet your strengths… but so true that it’s hard to stay confident sometimes. A story like yours does help, thank you 🙂