When I was working as the senior editor at Rock and Ice magazine, there was one year when I had to put my foot down.

“Do you think that we could go, I dunno, at least three issues without putting the Stonemasters on the cover?” I whined.

My complaint was mostly rhetorical. People love the Stonemasters. I love the Stonemasters. Everyone loves the Stonemasters. Put “Stonemasters” on a cover and you’re guaranteed to sell issues.

But sometimes I thought, Geez, hasn’t anyone else done anything cool in climbing besides the Stonemasters?! By so frequently writing about a group of dudes who did all their most important ascents almost 40 years ago, I felt as if we were all guilty of chronic Stonemasturbating.

My half-rhetorical protest was taken half-seriously by my coworkers. I think we made it at least four issues without a Stonemasters reference … And to be honest, it wasn’t easy. The Stonemasters are the cultural nucleus of our sport. We’re all just a bunch of electrons doomed to buzz around their colossal mass.

Several months ago I caught an advanced screening of Valley Uprising, the star (and only) feature film in this year’s REEL ROCK tour. From the tireless and talented producers Nick Rosen and Peter Mortimer at Sender Films, Valley Uprising has been years in the making. In fact, I’ve been hearing about this film for as long as I’ve know Nick and Pete. Huge congrats to all my friends at Sender Films and Big Up Productions for finally finishing this incredible legacy project.

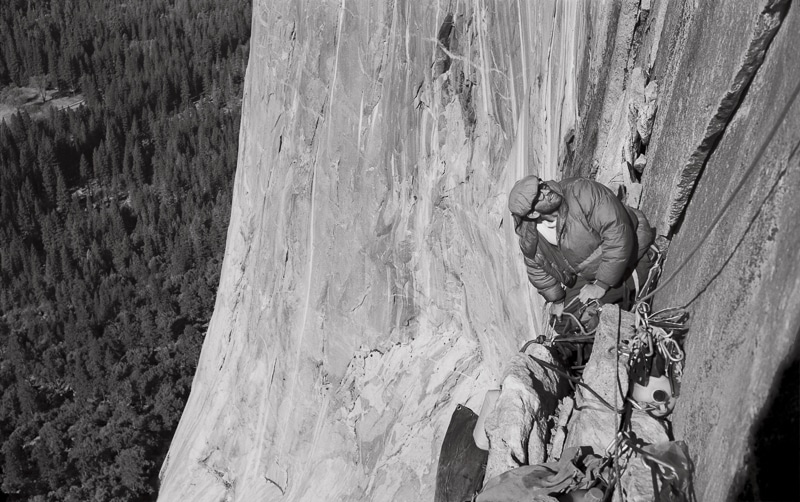

Valley Uprising is the story of modern rock climbing in Yosemite—which is to say, the story of modern rock climbing period. If you’re a climber, then Valley Uprising is our Bible: chapter Genesis. This film shows how climbing as we know it came to be. Our culture, style, norms, rules, gear, ideas and attitudes: all were tempered within the crucible that is The Valley.

With a heavy focus on personality and image, Valley Uprising paints a portrait of climbing as a counter-cultural response to the risk-averse climate of post-War America. Climbing was, is and always will be a refuge for those who don’t want to buy into traditional norms. Do drugs, drink hard, fuck authority and live free. (Maybe even go climbing, too!) Right on!

Beginning with the climbers of Yosemite’s “Golden Age” (1955-1970), then going to the Stonemasters era (1973-1980), then continuing up to this day with the so-called “Stone Monkey” era (1998-present), Valley Uprising shows a Yosemite-centric evolution of rock climbing through some of the most iconic and mythologized figures in our sport’s pantheon. John Salathé, Warren Harding, Royal Robbins, Jim Bridwell, John Bachar, Lynn Hill, Dean Potter and Alex Honnold: These are the climbing stars who form the constellations toward which Valley Uprising sails.

I consider Valley Uprising MANDATORY viewing for all climbers—ESPECIALLY if you’re one of those young/new climbers who thinks Royal Robbins is a clothing line and Warren Harding was a president.

Don’t be ashamed of your woeful ignorance. Just fix it, right now, and get up to speed on your sport’s roots. Purchase Valley Uprising on Vimeo on Demand.

Before you watch the film, consider this question: Why has REEL ROCK shifted gears this year, from showing us incredible new footage of climbing’s state-of-the-art to instead looking back at a set of archival images that revisit the most well-known stories of our sport’s inescapably Yosemite-centric past?

I ask that question not as a shallow critique of REEL ROCK but because I believe there is a profound response. Think about it.

Why are we watching this film in 2014—really? And what does our pervasive nostalgia for 1970s-era Yosemite climbing culture suggest about our sport today?

The question of whether we even are nostalgic for Yosemite’s Golden Age and Stonemaster era, I think, is answered by the fact Valley Uprising is the only film in this year’s REEL ROCK tour. Obviously, we’re nostalgic. This film isn’t made just for a core climbing audience, but for a mainstream one as well. In other words, people who aren’t even climbers are probably nostalgic for Yosemite in the 1970s, even if they don’t know it yet.

One area in which I think Sender Films is exceptional is that their storytelling often does a fantastic job of walking the fine line between core and mainstream audiences—including one group while not alienating another. This is not an easy feat, trust me, and it really speaks to Pete Mortimer and Nick Rosen’s keen sense of what people will find interesting.

Yet perhaps as a result of this inclusivity, Valley Uprising focuses more on image and personality and less on substance. You see this through the numerous references to all the climbers’ preferences for drugs, booze and free-spirited living; through their constant championing of such abstract (ultimately meaningless) ideals like boldness and risk; and through countless mythologizing hyperboles like “We were running on adrenaline and uncontainable ambition” (Largo).

But you also see the filmmakers’ preference for image by counting who is included in the film, and who is not. Valley Uprising is certainly one side of Yosemite’s story, but it’s far from the whole one (as I’m sure Rosen and Mortimer would concede).

According to Valley Uprising, there were three periods worth mentioning: the Golden Age (1953-1970), the Stonemasters (1973-1980) and the Stone Monkeys (1998-present). There is no mention of Max Jones, Mark Hudon, Kurt Smith, Todd Skinner, Paul Piana, or Alex and Thomas Huber (there are others, too, but to me those were the most glaring omissions). If Valley Uprising aims to show how climbing in Yosemite has progressed and evolved, to not mention these absolute visionaries actually feels like a major injustice.

Yet at the same time, I wouldn’t have cut anyone who is already in the film to put those others in, despite the fact that I’ve never been a huge proponent of the Stone Monkey’s media machine that somehow finds a way to awkwardly insert itself and its legacy at every opportunity it gets. …

Again, I’m not critiquing the filmmakers but rather building a case that Valley Uprising is more about satisfying our nostalgia for Yosemite in the 1970s than it is about providing an accurate depiction of the evolution of big-wall free climbing. And in terms of being able to alleviate our deep nostalgia for the past, Hudon and Jones, Skinner and Piana, and even the Huber brothers just don’t cut it. They don’t fit into that narrative of hard-driving, drug-taking, image-obsessed Stonemasters, which is the narrative that we, apparently, need today. They never have fit into that narrative, and that’s why their legacies will remain diminished.

Nostalgia has the Greek roots nostos, meaning “return home,” and algia, meaning “longing.” An academic essay by Svetlana Boym defines nostalgia as a “longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed. Nostalgia is a sentiment of loss and displacement, but it is also a romance with one’s own fantasy.”

In other words, nostalgia is a yearning for a utopia gone. And that really is the story of Yosemite in general. If Valley Uprising is climbing’s “Genesis” story, then consider all the ways in which we’ve fallen from Eden—not just with sport climbing and bolts playing the part of forbidden fruit, but also in terms of how Yosemite has so drastically changed from an untapped wilderness 100 years ago to today’s scene of draconian regulations and appalling commercialization.

I’ll be honest. I thought Valley Uprising was an overwhelmingly sad film. Though the film is peppered with fun moments and one liners that made me laugh, in general I was deeply depressed by Valley Uprising.

“The Stonemasters fit what [Yosemite] was. They didn’t fit what it became,” Largo pontificates, accurately. Perhaps our nostalgia for Yosemite in the 1970s can be explained by some kind of perpetuating desire deep in our collective unconscious to hear stories about how Eden was taken away from us. On so many levels, Yosemite is that story.

The Valley really has become a shitty place to hang out, and it only seems to be getting shittier every year. But who is going to do anything about it?

“The Stonemasters were all about pushing the limit and pissing off the status quo,” said Steve Roper in the film. Compare that to today’s brand of climber. We are doing a fantastic job of pushing the limits—better than any climbing generation before us. Yet we are not pissing off the status quo. Far from it. This current generation is not rebelling or fighting for our freedom. Rather, we have evolved to become a generation with a particularly high tolerance for restriction in our lives. When we’re forced to sneak through these increasingly constrictive loopholes to occasionally catch that glimpse of unbound freedom, we’re not pissed off about having to sneak through the loopholes, but grateful. Look at Honnold who, we see in the film, commuting in and out of the Park each day. It’s a hassle, he admits, but he quickly qualifies that grievance with a sort of melancholic and simple gratitude just for being able to climb in Yosemite at any level at all.

I wonder if our deeply repressed grievances over the restrictions we all face on our freedom today explains our profound nostalgia for 1970s-era Yosemite. Perhaps, but there’s more.

It’s not just we climbers who are nostalgic. Nostalgia is perhaps the defining symptom of our age. Everywhere you look people are recycling the past. Thanks to all our digital archives in which every waking moment of our lives are increasingly documented through photographs and videos, it has never been easier to do this. Just go onto the internet if you want relive recent history and vicariously install yourself in a different frame of time and mind. The result is a pop cultural stasis unlike we’ve ever known. This is true in music (Diddy “takin’ hits from the 80’s, make it sound so cra-zay!”; Girl Talk; etc.) and film (just look at all the remakes and sequels).

The entire hipster culture is nothing if not genuine nostalgia, loosely wrapped in extreme irony.

Periods of intense nostalgia have also been noted to follow revolutions. The French Revolution, the Russian Revolution and the end of the Cold War all resulted in political and cultural manifestations of nostalgia in those societies. I suspect the same is true for us as we attempt to make sense of our own “Uprising,” which of course was the climbing revolution that took place in Yosemite. It’s ironic that a historical film reliving climbing’s 60-year-old past could unintentionally become the most appropriate film for all of us today—not through its content, per se, but rather through our obsessive desire to relive it.

Look at how far and how fast climbing has gone. Royal Robbins, the architect of our entire sport, is still alive and kicking. Climbing is just not that old—but my how it has changed! The demographic of climbing today is one in which we have of everyone from OG godfather Royal Robbins all the way down to Ashima Shiraishi.

It makes a lot of sense that we’re feeling so confused about what climbing is supposed to look like; that we’re fatigued by hearing about the astronomic leaps and bounds in difficulty grades each season; and that some part of us just wishes to return to a place when climbing was simpler and in some ways, better. All of this explains why Valley Uprising might be the only film in REEL ROCK this year. What other stories are there that are worth telling today? Do you really want to see another film of Sharma climbing some 5.15?

Halfway through Valley Uprising, Lynn Hill produced this extra prescient nugget: “If you start believing your own myth, that can mess you up.”

There was another reason that I found Valley Uprising quite sad, beyond just the aforementioned Jungian lamentations over paradise lost. And that was because Valley Uprising doesn’t shy away from showing the truly negative aspects of our sport. Though I have to admit, I’m not entirely sure this was a conscious decision by the filmmakers. Valley Uprising is a wholly sad story. At each turn, our heroes fall from grace and what we’re left with is the reality that the foundation of our sport was built on nothing more than flimsy egomania. Here’s what I mean:

The film begins with the Golden Age of climbers who arrive in Yosemite with great, noble intentions: the pursuit of adventure in the face of a risk-averse American culture in the aftermath of World War II. Royal Robbins and Warren Harding are true American pioneers in every sense. Yet this story quickly devolves into a personality pissing match between two monstrous egos that gets played out on the rock (and at the rock’s expense). And when their conflict reaches its natural apogee on the Dawn Wall, we learn that neither Robbins nor Harding ever climb in Yosemite again, suggesting that they didn’t really love the sport; they were just driven by their own ego all along.

Robbins goes off to become a big corporate businessman while Harding drinks himself to death on his mother’s porch.

Then we come to the film’s main attraction: The Stonemasters: Again, they show up in the Valley with great, noble ambition and the fire and talent to do great things (though apparently, it was mostly all about the drugs). Yet their tight-knit group dissolves when individual egos grow to uncontainable proportions. People disperse, become embittered and disparage things like sport climbing while living out an honestly lonely existence.

Nothing, apparently, happened in Yosemite in the 1980s because the film fast-forwards to the 1990s, when it provides a quick obligatory nod to the movie’s single female character, Lynn Hill, for freeing the Nose—“It goes, boys!” Then we’re off, fast-forwarding to Dean Potter, the Stone Monkeys and Alex Honnold. And here the film gets muddled and confusing because the focus is less on climbing, and more on its tangential outgrowths such as high-lining and BASE jumping.

Again, that Valley Uprising loses its focus during this era of Yosemite speaks not only to the fact that the Stone Monkeys aren’t a real thing—just an image-obsessed regurgitation of the Stonemasters (again, a result of this particular brand of nostalgia)—but it also speaks to the fact that climbing has gotten so huge that we have completely lost our ability to see it with any clarity.

There are so many facets to climbing today. If you were asked to paint a complete picture of climbing today to someone who doesn’t climb, where would you even begin? The very thought of trying to do that overwhelms me.

Also, none of today’s climbers fit the traditional narrative and myth that we want to continue telling ourselves. Tommy Caldwell is going to free the Dawn Wall using wholesale sport tactics, including the addition of new bolts, fixed ropes and multi-year sieges—yet how does that honestly reconcile with the Harding/Robbins rivalry? It doesn’t (and that’s OK).

Alex Honnold, the boldest climber of our time, learned to climb in a gym.

And the best female climber in the world might actually be a 13-year-old girl with bangs.

Climbing as a sport, lifestyle and culture has become so enormous that it’s impossible to fit today’s climbing landscape on a single canvas. It’s confusing and nuanced and not at all simple and that, perhaps, it makes us yearn nostalgically for those simpler times.

The result of nostalgia is a mythologizing of the past—a desire to turn what once was into what we wish it was like. Perhaps because we all yearn to be in a different place or time—something perfect like in our childhood.

Valley Uprising is a symptom of our pervasive nostalgia for 1970s Yosemite culture—but perhaps, it’s also the cure. When I watched it, I was reminded that many of these larger-than-life titans of climbing were largely motivated by image and ego. It’s something I guess I’ve always known, but it was quite another thing for me to see it on a big screen. In that regard, I suppose this is a good thing. Perhaps Valley Uprising will ultimately help relieve us of our nostalgia—by reminding us that the past wasn’t all that great either.

Thoughtful review & honed prose. Thanks for taking the time to spin an intriguing review.

Having spent time living in the park both as a legit working and illegitimate dirtbagging presence, I’ve experienced both the justified glorification of the masters & monkeys as well as the sadness and irony inherent in aspects of their lives & culture.

Stoked to see the film!

Wow…

Great review Andrew,

Happy to see the Stone Monkeys getting a bit called out. My first real season in the Valley was ’98 and pretty much spent the next 14 years there. I never really considered myself a monkey though I was there smoking weed with Cedar, Stanley, Winkie and Coiler on top of the 5.2/5.12 boulder every morning. Its always felt like a bunch of people talking about themselves in first person, it’s all just a bit self important to me.

Thanks Mikey … Great comment

Interesting and very thoughtful take on the film. It’s been amazing to see the level of hype around this film. It’s almost Harding-like in its media efforts to be seen. For the past couple of Reel Rock tours, the local LCO has sponsored the showing but we’re hedging a bit now as we’re not sure the “fuck the man!” message is something we really want to promote / endorse at a time when climbers are putting more and more pressure on public lands in the state. I also wonder how relevant the Valley nostalgia is going to be to climbers who increasingly think that every route needs a bolt and permadraws.

I think you, Mr Bisharat, write the best perspective pieces on climbing, and thank you for this one. It echoes many of my own sentiments, and offered a number of expansions and new directions of those ideas.

The thing that bothers me about Yosemite is not that I’m not allowed to be there for very long, or that it can feel like a police state if you’re a climber, or that everything is so expensive, or that there are bajillions of RVs (which should not be allowed there), (though of course these things aren’t great), it’s that there’s such a double standard: as long as you have money, you can do what you like. If you are an average American kid, and you want to experience one of the greatest American resources, be ready to wait in line behind the people with money. In 2005, I was only allowed to be in Camp 4 for 2 weeks, but if I could afford it, I could have stayed in the Ahwanee all year. Basically, the park service is trying to make the maximum amount of money for every entrant into the park, rather than trying to distribute this amazing resource to as many people as possible. This is a limited resource, and they have decided to let money decide who gets to use it.

So yeah, that’s offensive to me (though this concept is as American as you can get), and I don’t go to the valley any more.

On another note, maybe there’s a literary technique at work here that I’m ignorant of, but I cannot help but say that it is the electrons that orbit the nucleus, and that the nucleus is composed of protons and neutrons.

Thanks for the great article. See you around.

Great comment, thanks Sean

Thoughtful, complex, and nuanced. And I mean your (AB’s) writing… Hoping I’m not feeding *your* ego too much! Ha!

Perhaps a piece of the future of climbing lies in the things you write about and how you think them. Climbing needs more voices like yours going forward. And I see them emerging out there, especially amongst your generation of climbers. I’m truly looking forward to more of this. It’s changed my outlook on climbing for the better.

One of my favorite lines (of several):

“…constant championing of such abstract (ultimately meaningless) ideals like boldness and risk…” A succinct distillation of pages of blather often found on the usual suspect forums. Thanks for helping make sense of these bigger perspectives.

Great work, AB! I’m nominating you for another Olga…

the award or the person? Either one sounds good to me!

Very interesting piece. Too good for the internet, for sure, so thank you.

I think that the Nostalgia that people in the Valley feel has a lot to do with whom prevailed there. Those who do not fit the image of the drug-abusing out-law of a stonemaster, do not wish to stay illegaly in the Valley anymore. It is people that mostly care about imitating the old and fighting the law that prevail – and often are terribly inefficient in their climbing. People like the Huber’s or TC or Honnold go climbing, and I doubt they are very nostalgic. Those still spending a lot of time talking about their own Monkey existence, the post-Cedar and post-Coiler generation, are irrelevant to the sport and should be to the audience.

That said, a lot of the current monkeys are really mellow guys that live in the Valley legitimately and climb well and don’t take themselves too seriously in terms of what they climb. Scott, or Cheyne, or Zack or Dan … etc.

The egomaniac monkeys are a small (albeit loud) but ultimately declining minority. It is interesting how you point out that they manage to be heard because of our general nostalgia.

Thanks for writing a good, original and in-depth review.

npb.

Something tells me that Mark, and Max are glad they were left out.

well, it doesn’t sound like Valley Uprising is any Brown Bunny. But, seriously, amazing review. Ironic that cedar is taking the bait but not surprising. Way to bust out some etymology. I’m really interested by your comment about the draconian regulations and how that affects the experience. I’m going to have to marinate on that one.

I’m looking forward to seeing the film. I am also looking forward to never having to hear about the goddamn Stonemasters, or their self-declared spiritual offspring, again. Perhaps this is just my personal take, but a pervasive sense of arriving on one scene or another just after the truly cool stuff all happened had followed me around since I can remember and the whole Stonemaster thing is merely one more example. Is this the sense of permanent nostalgia you speak of? There’s always an Eden, and you just missed it, but boy was it cool. You shoulda been there. This pulls one’s attention away from the present, and what good is that? I climb because I enjoy the movement, position, focus, all of that stuff you already know, and I’d probably be having a better time of it if I wasn’t consciously or subconsciously trying to insert myself into some kind of Larger Narrative that doesn’t include me anyway.

Thank god Tom Wolfe never got around to the Valley, or the entire world would see climbing the way they now see the Pranksters, or the Pump House Gang. At least we can still kind of be off on our own over here, happily misunderstood, answering questions at Thanksgiving about whether we aspire to climb Mount Everest.

Thanks Rob, interesting comment … I can’t imagine how many Zings and Zangs! and Takes! And Fallings! Tom Wolfe would write if he ever covered climbing … I would be interested in hearing his take on climbers’ self-images though …

was it something I said?

You have an interesting take on the “nostalgia”. To me this movie is a new look at a cool place, where some neat stories were made by some rather interesting folk. Route histories and FA personalities are what bring climbs to life. Being at “Thank God Ledge” and thinking about how the boys felt when they found the feature, adds wonderful perspective when climbing Half Dome etc. But I’m just a simple construction worker, who dreams of climbing el Cap, loves these stories, and is stoked to see the movie.

I’m not about to vote for any of these personalities for president, but I sure love hearing about them climb.

Indeed …

I feel the same way David. I’m just a weekend warrior who started climbing 6 years ago at the age of 35, is satisfied to climb trade routes that push my leading ability, and thought climbing the NWFHD was a huge accomplishment (even if we did haul). I love how the history of each climb adds to the richness and wonder of climbing in the Valley. Whether it’s the awe of how Royal, Jerry, and Mike discovered TGL at just the right time, or one pitch later freaking out about Alex free-soloing the bolted slab below the summit. Haven’t seen VU yet – doesn’t come to my neck of the woods till next week- but I’ve got my ticket and can’t wait to feel a deeper connection to a place and sport I have grown to love.

Great article Andrew,

This is the most insightful piece of work I’ve read on climbing culture to date. Great perspective on the self-involved egos that shaped our inherently self-involved sport.

And for what its worth I think the complexity of today’s climbing culture should be celebrated. As time goes on, things/activities/sports take on different meanings. For the stone masters climbing might have been a countercultural release, but that doesn’t mean it has to or should be the same for the rest of us.

Love the site and your work Andrew, thank you.

Thanks Tyler. That means a lot, man! Thanks

First off great article. Second, I am so happy that you quoted Boym and that I actually know who she is. In my nerdy, English-major head I yelled in triumph that I knew what the hell you were talking about.

haha! Awesome!

I watched this last night in a chilly Chautauqua Auditorium. Nice to see the cross-generational cast of Largo, Lynn, Dean, Alex, Tommy, and Doug up there on stage.

Valley Uprising is to climbing film as Riding Giants (2004) is to surf film and Dogtown and Z-Boys (2001) is to skateboard film. While Andrew’s review is interesting and well-written, the answer to why this film is out now in 2014 is much simpler than Andrew proposes. Nick and Peter and crew looked around and saw there was no equivalent in the climbing world to the aforementioned documentaries. And surely achieving the same commercial success that the other two achieved would be an obvious goal. Of course, to do so requires talking to a broader audience evident by the fact that they need to depict how tall Half Dome and El Cap are relative to the Empire State building, the difference between free and aid climbing — what climber doesn’t know that? Plus, this film took 7 years to make so this really is mid-2000 idea finally coming to fruition.

Great, thought provoking post Andrew. However, a few of your remarks seem out of character with the theme you tried to weave through the article. It seems like you are trying to dispel the nostalgic warm and fuzzies everyone feels about the 70s climbing in scene in Yosemite, but then you make comments like these:

“Yosemite has so drastically changed from an untapped wilderness 100 years ago to today’s scene of draconian regulations and appalling commercialization.”

and,

“The Valley really has become a shitty place to hang out, and it only seems to be getting shittier every year. But who is going to do anything about it? […] This current generation is not rebelling or fighting for our freedom. Rather, we have evolved to become a generation with a particularly high tolerance for restriction in our lives.”

These sort of comments are the sort of boilerplate, pro forma lines that almost every climber feels compelled to write about Yosemite these days. Indeed, this is itself a direct result of the misplaced nostalgia you claim to be dispelling. Let’s start with the first one. Yosemite was not “untapped wilderness” 100 years ago, nor 150 years ago. From almost the first year it was discovered by us white men as we slaughtered and displaced the natives, Yosemite has been commercialized. The only “golden age” of a Yosemite without commercialization, regulation, or environmental degradation would have been before any non-native person entered the Valley. Yosemite climbing, as a part of the larger history of Yosemite National Park, doesn’t exist outside of that legacy. Indeed, for all intents and purposes, Yosemite climbing doesn’t exist as we know it without those three “big sins.”

And what of the regulations? Climbers in particular seem singularly obsessed with bitching about camping regulations in the Valley while simultaneously proclaiming their staunch love of the wilderness and the environment of the area at large. Yet no one seems to be able to articulate exactly how the situation could be any different. Sure, everything was hunky dory in the 50s and 60s, when park visitation was 1/3 of what it is today, when people could just set up tents wherever they wanted to in Camp 4 and stay for months. But every climber seems to neglect to mention how, until the Park started regulating camping more, the campgrounds and surrounding areas were being “loved to death”: trampled, degraded, and eroded. Not to mention the fact that groups of campers staking out sites for long periods of time prevents others from coming and finding camping. Poor family from the Central Valley that wants to come camp for a weekend under Ponderosa Pine and Granite? Screw them, I have routes to climb and a nostalgia to rekindle.

So of course people today chafe at the 7-day limits and the bear boxes and all of that. But we chafe at it because we as climbers like to think of ourselves as existing in a vacuum, above the normal riff-raff and unwashed proletariat masses surging through our Valley. Of course, we don’t exist in a vacuum and – as the trash at the base of popular crags and the shit dripping off El Cap attests to – we ourselves can be just as trashy and short-sighted as other visitors to Yosemite. There is limited space, and increasingly large groups of people who want to be there. Unless we are stoked on razing some more forest to make way for more campgrounds, I don’t think there is much to be done. And, one might wonder, why exactly are there more and more climbers crowding onto the same routes and the same campgrounds? Well, a generation that grows up reading in every second or third issue of Rock & Ice or Climbing about the “Golden Age” and the “Stonemasters” might just find itself interested in traveling there to relive those collective memories. You, of course, understand that, but you yourself also contribute to it by perpetuating those memories. It’s a sort of Catch 22.

Naturally, as a modern Yosemite climber, I am a total pussy. I heed the rules, I store my food in a bear locker, I climb when I can and go elsewhere when I can’t. Guess what? The climbing still kicks ass in Yosemite. The cracks are still splitter, the slabs are still scary, and the granite still seems to go on and on forever. Everything has changed, and yet things are still much the same. Those who care more about climbing than about how their experience relates to some fantastical version of the past continue to find inspiration and stoke among the Valley’s walls and boulders. I have a feeling that won’t change any time soon.

Right on!

great comment man, thanks

This comment is the best thing I’ve read about climbing in a long time, maybe ever. In my opinion, there’s not much to be nostalgic for if you’re in it for the climbing and the connection with nature.

This is so thought provoking, Andrew. Thank you!

One of the reasons I didn’t care to learn much about our history when I was a new climber was because I didn’t relate at all to the anti-conforming, partying, dirtbagging scene. But what I do think we all relate to and long for — and you elude to this in your post — is freedom.

What the Golden Age & the Stonemasters had was a pioneering, wild-west spirit. El Cap was insurmountable; no one believed it could be climbed! How long they must have looked at the Captain with wonder? When they began their attempts, they had to scavenge gear from scrap yards and create it in foundries.

Today, you can get the beta for any route on-line. You can watch someone send just about any boulder problem on you tube. Gear is phenomenally high-tech and readily available. We can take clinics at gyms and read books to improve our training & technique.

There is no more sense of wonder and discovery. Not so big a sense of accomplishment and pride from stepping into the mystery and persevering. I think some of our nostalgia is for that and the brotherhood that comes from being on the cutting edge, where the sense of freedom is vast.

great comment, thank you Paisley. I think you’re onto something that needs to be discussed further: the extreme paradigm/mentality shift that has resulted from an era where only possibilities exist to one where it’s only possible to do “more of the same”

Andrew, I think there are a couple things going on here worthy of discussion. One, climbing has boomed. The community is so big now that it’s more difficult to get that sense of connection and brotherhood that was much easier when the cast of characters was small. One doesn’t feel as special or noticeable now, I think. As an example, even when I started, in 1992, there were very few women climbing. I identified with that at the time, and it gave me a special place in my local community. Now there are tons of women climbing and it isn’t very unique.

It’s easier to push the edge when you feel supported and part of something bigger. The ego does get stroked, but it’s also true that contributing helps the whole community. (I’m a perpetual optimist, especially when it comes to believing in the good of people!) You could also say, from a more cynical stance, that in a smaller group, everyone knows who you are and what you did or didn’t do. You wouldn’t want to look bad in front of your peers, so you better prove your worth, and that makes people push to new edges, too. Either way, the size of the community plays a huge part in the mental shift.

Second, with all the low-hanging fruit picked, finding more possibility requires greater effort. You either need to go deeper into the wilderness, or be climbing 5.13 or harder. My husband (the perpetual realist) would say people are lazy and most don’t want to do the work of finding, cleaning and (perhaps) bolting new lines. I think there’s some truth to that. But I also believe a lot of us are now trying to live a life of balance, juggling career and family/relationship with climbing. It makes it more difficult to do anything but “more of the same” yet it presents a new edge that didn’t exist for the Stonemasters who, for the most part, were only climbing, not raising kids or upholding careers.

Some of us are really interested in leaving this legacy, in creating things for ourselves, but also for the climbers that come after us. Some of us find that living a more balanced life IS pushing the edge. It’s much more challenging to kick ass as a climber when it’s not the only thing you do! This paradigm shift is definitely a multi-faceted change, and a really interesting one to ponder. You’re article has stimulated several deep conversations in our house, and we are thankful for that! Looking forward to hearing more of your thought on it…

Insightful commentary as always Andrew. Great to see other’s viewpoints. Have to say though I don’t get how you could be “sad” after seeing this movie. e.g., “I thought Valley Uprising was an overwhelmingly sad film. Though the film is peppered with fun moments and one liners that made me laugh, in general I was deeply depressed by Valley Uprising.” and “There was another reason that I found Valley Uprising quite sad…” and “Valley Uprising is a wholly sad story.” I left that theater STOKED and ready to get out the harness and tie in again. So it’s more Endless Summer than Dosage V. Maybe that’s what climbing needs now.

So, I watched the movie a couple of days ago with a bunch of friends and our kids. The children were obviously completely impervious to the nostalgia aspect of the movie, and loved it. They liked the crazy stories, the weird personalities and were in awe of the climbing. All weekend, they were asking me, “could you climb the Dawn Wall?” “How big is that mountain over there, is it as big as Yosemite…” Seeing it through their eyes, I didn’t end up being left with any feeling of sadness at all, even after being ready to feel melancholy after reading your review. My point is, I think you fell into a bit of navel gazing, searching for something to write about. This was one of the best climbing movies I’ve seen, if not the best.

Great article. But really, what do you mean by “Jungian Lamentations”? Never heard that term before!

I just made it up

Electrons zoom around center nuclear masses, not protons.