I sank three fingers into a sharp pin scar above my head, my arm at max span. I exhaled and released tension on my lower hand while trying to keep my hips from shooting out right. Just as my left hand grazed the next hold, my right hand blew out of the pin scar and I took another fall onto a rusty fixed pin.

How many more falls is that pin gonna take? I wondered.

I sagged into my harness and looked at the blood seeping through the tape on my index finger. My fall had pulled Cass, my belayer, up into space such that his tethers were taught against our belay anchor. Cass is lean, with long muscles stretching over a lanky frame that gives him a kind of climbing endurance that I wish I had. From my vantage, he looked like a spider in its web.

He lowered me back to the start of the pitch. I untied and pulled the rope to get another burn on the crux of the largest freestanding sandstone tower in the world, the Titan.

“We’ve been projecting this section for the same time it took us to send the first five pitches,” Cass said, laughing.

“I bet we’ve tried this move 20 times each,” I said.

We had already onsighted the first three pitches on lead and following. I got pitch 4 second try, and Cass onsighted it following. We had climbed past ancient gargoyle formations and over sandstone bridges on pitches 5 and 6.

I almost didn’t even take in the alien landscape because I was too busy. Busy planning my Instagram victory caption from the summit. Busy thinking about how I was a few pitches away from completing a résumé-worthy climb that would turn sponsors heads. I imagined life as a big shot. I’d start speaking in mellow, understated humblebrag, when recanting the tale.

Yeah, it was kind of sketchy I guess, that’s why we just didn’t fall, you know?

This pitch, however, was revealing itself to be a punch to my overly inflated ego.

“I’m gonna go crazy if this one move stands between us and freeing the entire tower,” I said.

“There’s also the last pitch. That one’s not supposed to be easy,” Cass added.

By that he meant scary.

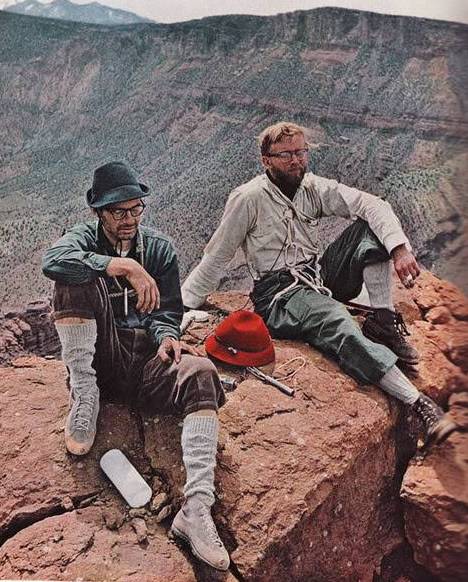

Just across from the more well-traveled and beloved climbing area of Castle Valley, Utah, are the Fisher Towers. Whereas Castle Valley is all bullet Wingate sandstone, the Fisher Towers, with their crude Moenkopi sandstone, are barely resisting collapse. This group of freestanding spires includes such iconic formations as Kingfisher, Ancient Art, the Oracle, and, of course, the mighty 900-foot Titan, which is the tallest of the group. The surface of the rock sloughs off with the scrape of a fingernail after a stiff rain. The Fishers resemble half-burnt red-wax candles.

For the past five pitches, Cass and I had been climbing our way through one of these human-sized runnels of “wax.” Our faces and clothes were covered in red dust. We were hoping to do a ground-up all-free ascent of the Titan and add our names to the short list of climbers who have freed this glorified vertical mud, which is shrouded in climbing history and lore that dates back much, much further.

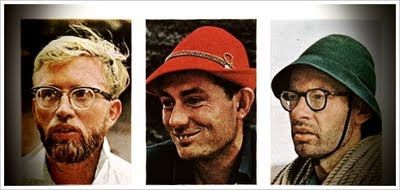

The first ascent of the Titan, in 1962, was a historic moment in climbing. In an expedition sponsored and documented by National Geographic, Layton Kor, Huntley Ingalls, and George Hurley, three of America’s top climbers, traveled to this rarely seen corner of eastern Utah to see if the Titan could even be climbed.

Kor and Ingalls had originally spotted the Fisher Towers from the top of Castleton Tower after establishing their namesake route, the Kor-Ingalls (5.9), on the south face of Castleton—a route that has since become the most popular desert-tower route in the world and is one of North America’s 50 Classics.

During the 1962 expedition to the Titan, which spanned several days, Kor, Ingalls, and Hurley aided muddy cracks and seams. They ultimately placed 52 expansion bolts, which included three-bolt anchors, a high bolt count that suggests the climbers were concerned by the integrity of the stone. (Rightly so!) They named the route the Finger of Fate, after the “finger” of rock that sticks up midway up the great rib. Their ascent was subsequently featured within a 1962 issue of National Geographic.

Years later, the Titan was repeated, though it remained relatively unpopular. Whereas a thousand climbers stood atop Castleton each year, the summit registered the Titan remained relatively barren.

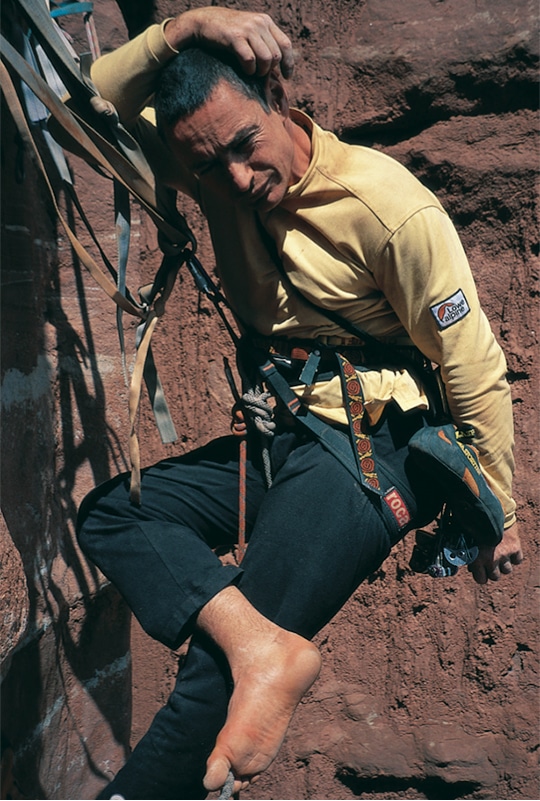

It took a certain kind of vision to consider free climbing in the Fisher Towers. In 1996, Stevie Haston, an iconoclastic British climber, attempted to nab the first free ascent of the Titan via the Finger of Fate. Stevie made a valiant effort but was shut down on the last pitch, a run-out 5.12, then still protected by the original bolts from the first ascent.

Years later, Haston returned to the Titan to try freeing Sundevil Chimney, a different route on the opposite aspect.

The first two pitches of Sundevil went at 5.13, solid for the grade and with adequate gear, while the rest of the route produced scarier, but easier free climbing. He later wrote an article called “Free Mud” in which he called Sundevil one of the best climbs he had ever done.

“Only being 6 feet above a solid bolt felt bland to me afterwards,” he wrote.

Years after Stevie’s first free ascent of the Titan, the last two pitches of Finger of Fate were re-bolted by the American Safe Climbing Association, as well as the belay anchors, making a free attempt on the Finger of Fate route more plausible.

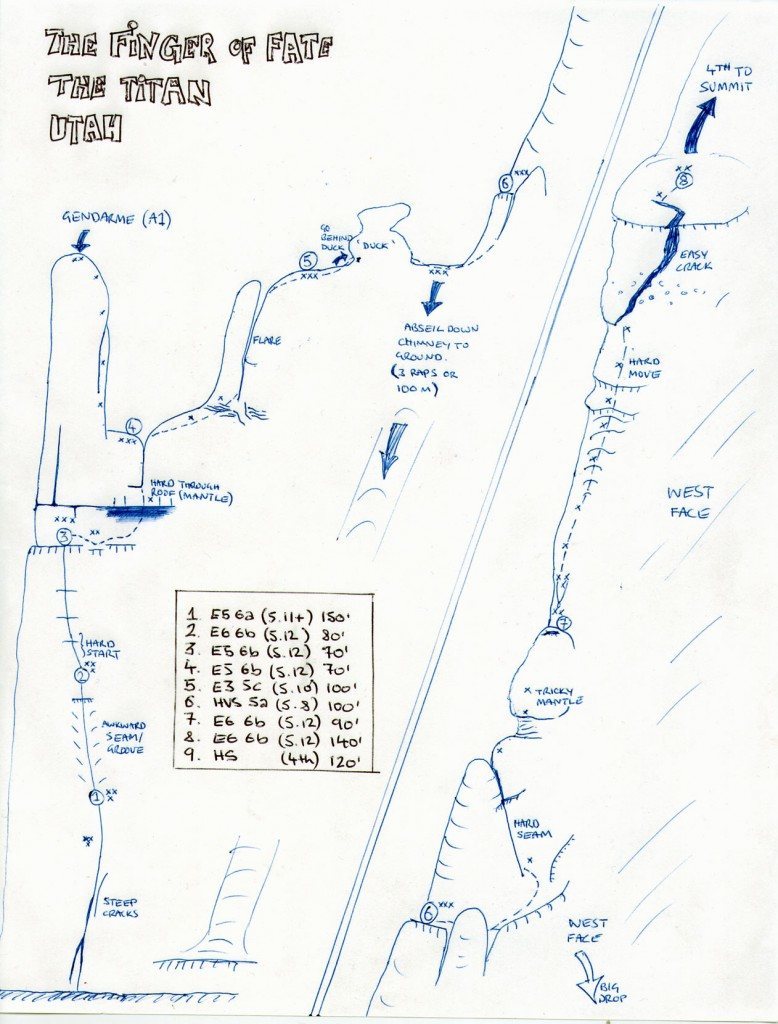

Ben Bransby and Pete Robbins, two of Britain’s best trad climbers, arrived and succeeded in freeing the Finger of Fate in 2005. The produced a hand-drawn topo with grades and humorously vague descriptions of each pitch. Things like “Tricky Mantle, 5.12 E6” or “Hard Move, 5.12 E5.”

Will Stanhope also got his own free ascent of the Finger of Fate with the help of Coleman Blakeslee, Jesse Huey, and Paul McSorley. Stanhope lead every pitch clean and the effort spanned several days, although he admitted to climbing the roof pitch with pre-placed gear.

The Titan again returned to the media when Alex Honnold and Cedar Wright documented their biking/climbing adventure in the film Sufferfest 2, in which Alex freed the route along with many other sufferable towers.

There may be a few other free ascents by now—but a free ascent of the Titan remains a rarity. Every time Cass and I told people we were considering freeing the route, they would reply incredulously, “People free climb that pile of choss?”

Cass is a dedicated desert rat, a history buff, and a kindred spirit with the Brits, the best trad climbers around. He was heading to the Fishers to aid-solo the Finger of Fate and rap down the Sundevil Chimney, to replace anchors, if necessary, for a friend who was keen to do his own free ascent of Sundevil.

When I heard that he was heading to the Finger of Fate, I jokingly suggested we should try to free it.

Cass and I have partnered up a few times before because we have similar climbing goals and enjoy a healthy competition with one another. We both enjoy soloing and climbing scary terrain, though we have different skills and approaches. We could not be more different in our climbing background and overall physique.

Cass is 25 years old, an electrician’s apprentice in Salt Lake, and he is currently in school at the University of Utah to study English. We met through the university’s climbing team three years ago, but our backgrounds couldn’t be more different.

Cass grew up climbing with his dad in Ogden Canyon. He’s spent a lot of time climbing around Indian Creek and exploring various alpine/trad zones. Meanwhile, I have spent a large portion of my 23 years in a climbing gym and Little Cottonwood Canyon. I dove headfirst into the competition side of climbing. Once engineering college was over, I moved into a van to experience the finer things in life, like whiskey and real rock.

In addition to different backgrounds, I have different climbing styles, too. I have a +8 ape index that makes me look like a gibbon on steroids. Naturally, I reach and thug my way through hard moves while Cass relies on his endless finger endurance to float. With such different styes, we can collaborate on projects and come up with some pretty good beta. When we climb together, neither of us feel pressure to be the rope gun, nor do we feel like we’re being dragged up something. Both can be the heroes of a day, pitch, or move.

As our plans formed for an in-a-day free ascent of the Finger of Fate, I chose to remain somewhat ignorant in my route research. I left that to Cass. He chose the gear, how we’d break down the pitches, and what kind of tea to bring.

Sometimes I think it’s better to be unaware of what you are about to endure rather than dwell on it. Cass poured over route descriptions and accounts of the climbing and worried until he had dreams of ripping entire pitches of gear out of the wall. Meanwhile, I went about my day and remained ignorant about the scary details of the climbing in hopes that it would help me climb the route devoid of fear.

We decided we would approach the Titan with three goals for maximum fun and suffering:

One: We would swing leads, with both people free climbing. If either did not send, they would be lowered back to the starting anchors to try again.

Two: We would try to free the route in a single push, the first day we got on it.

Three: We would place all gear on lead to get the cleanest redpoint/onsight possible.

Now that we had a goal, and clarity about our style, all that was left was heading up onto the tower to see what kind of adventure we were going to have.

Rage Beta: The act of climbing to suss beta for future attempts while raging as hard as possible in hopes that a future attempt of the climb won’t be necessary.

We have this boulder so dialed, we just need to fire it,” Cass said.

“Yeah we have the beta, but I don’t know how much more Rage Beta my body can handle,” I say, rubbing my tattered fingers.

“Seriously though, it’s just a mental block. We have fallen at the same spot enough times that it is becoming part of the routine. Our minds submit to the fall.”

He was right about at least one thing. We had the boulder problem so dialed that even with fatigue it should be possible. However, we were also battling the clock, as the sun was about to peek around. In the heat, the climbing would become that much harder. I was worried that we had spent too much energy and skin already. We were wrecking ourselves on this pitch, but both knew there was hard climbing still to come.

We decided to rest for 20 minutes to give ourselves an attempt or two each to send before the sun hit the rock.

We entertained the idea of pulling on gear. It would still be an a proud ascent in my book, but it would be bittersweet. Only 15 feet of climbing stood between us and a chance of finishing what we had started. The thought of joining Stanhope, Honnold, Stevie—our heroes—in the summit registry steeled my will.

We can do it.

I got back on the sharp end. The sun was almost touching the seam and was floodlighting the belay stance with heat. I flowed through the opening moves placed my feet precisely in a lieback. I felt as if I was climbing really well.

But it wasn’t enough. My hands started slipping out of the scars.

I gripped harder, recalling my bouldering reserves, and willing myself stop my core from sagging. I crossed that threshold of the fall point, the part of the route that had become a routine, a mental block, and pulled my feet up and am over the lip.

I yelled so loudly that an aid climbing party who had been tailing us for the past few hours probably though one of us had zippered and decked.

Cass was all wide-eyed and yelling, too. Now it was his turn to send.

I lowered back to the ledge so that Cass could get a chance to redpoint the pitch on lead. Due to the nature of this particular pitch, Cass would’ve only had one attempt to get it clean if he was following; otherwise, he’d be out in space and wouldn’t be able to lower back to the start of the pitch.

Cass flowed through the opening sequence, pulled through the crux, and slapped a previously unused sloper high and left. He got to the good hold, the one that marks the end of the hard climbing, and started mantling over the lip. Then his feet slid, and he fell back onto the fixed pin. With mixed feelings, he lowered back down.

“I basically did it,” he said.

“Yeah, you did the last hard move,” I assured him.

Since I had sent the pitch clean on lead, we were still following the most important part of our first rule, but we’d be breaking the second half of our rule if we continued on without Cass making a proper free ascent of the pitch. I waited for Cass to talk.

“I still have to lead pitch 8,” he said. “The one that stumped Stevie. … All right, you should just go ahead and climb to the next anchor, and I’ll give pitch 8 my best.”

I wanted to let him know he could try again, that I’d be willing to spend all night supporting him working it, but I didn’t say anything. I was torn between realizing my own dream and realizing it with Cass alongside me.

Cass handed me the gear, and I climbed to the anchors and put Cass on belay to follow. It wouldn’t have been easy for Cass to pull through the boulder problem on toprope, but I assumed he was going to pull on gear to save energy for his lead of the last hard pitch. Instead, I felt a steady slack on the rope, meaning that he was climbing free. I heard a yell as he cleared through the crux, and a minute later, his head popped over the lip.

“Dude, I sent the boulder!”

Cass had stepped up and gotten it done on the last possible try.

Now we had all the momentum. Our fingers seemed to hurt less and bodies became more willing to move. Most importantly, we’d left our egos behind on the boulder problem.

Cass racked up for the last pitch. The tower narrowed dramatically here, resulting in spectacular exposure. We could see down almost all sides, 900 feet to the desert floor. The wind howled as we transferred gear at the semi-hanging belay.

The last pitch was an insecure 5.12. As Cass headed up on the pitch, it looked like he was wrestling a red monster. Though still exposed and run-out, the pitch was much safer thanks to the re-bolting. Heel-hooking, kneebarring, and crimping on pebbles sticking out of the mud, Cass took several tries to find the correct beta. He lowered to the anchors after trying to crux once. He barely rested, so excited to have figured out the moves.

Five minutes later, he was off to send the pitch. As Cass climbed out of sight to the summit, the rope tightened on me, and it was my turn to climb. As I flashed up the pitch, I thought about the legends who’d left their marks on this route, from Layton Kor and Stevie Haston, to Pete Robbins and Ben Bransby. I was thankful for their vision. I was even thankful for the vision of the re-bolters because we probably wouldn’t be here without them.

On the summit, I gave Cass a hug and cracked a tin of oysters. The winds were dying down, and my body warmed in the sun, warmed with a sense of fulfillment. All around the painted desert landscape bloomed with its timeless aura. Atop the Titan, I felt at once further away from other people than anywhere else I’ve been, yet simultaneously closer to another human than I have in a long time.

0 Comments