Waterproof-breathable (W/B) fabrics have a place in the climbing world. Unfortunately, that place is often at the bottom of your backpack.

For as long as I’ve been a climber, much of the outdoor industry, led in particular by Gore-Tex, has pumped the fear of god into me that every drop of moisture that falls from the heavens is one drop closer to my own death by exposure. This brand of marketing has been so effective, in fact, that it has caused climbers like me to wear what amount to $400 Bikram-grade garbage-bags around their torsos and legs, even in perfectly sunny conditions, as they slog up snow, ice and rock toward their own sweaty summit victories.

Typically, water resistance, or waterproofness, is determined by how much water, in mm, can be suspended above a piece of fabric before it penetrates through. (Also it may be sometimes measured in psi). Depending on who you are talking to, the classification of “waterproof” begins around ratings of 2,500mm to 5,000mm.

Breathability is the rate at which water vapor passes through the fabric, measured by grams of water vapor per square meter of fabric per 24-hour period (g/m2/d), often abbreviated to just “g.” There are typically four different tests that may be used to derive this measurement—and all four are prone to yielding different results.

Gear freaks and lab rats like to tweak out over such calculations, but true dirtbags don’t give a rip about any of that. The only rip we climbers give is the immediate crampon spike we put through our brand-new $400 Gore-Tex pants. DOH!

The marketing hype has you believe that the minute differences between each brand’s own recorded performance measurements will drastically affect outcomes in real-world climbing situations. But of course, we all know that that’s not true.

You’ll never hear a climber say, “We were only 200 meters up a gnarly new Himalayan wall, but in just 24 hours I’d produced over 9,000g of water vapor within the square meter that is my torso and armpits. Alas, my jacket was only rated to 4,500g … So, you know. We bailed. #MagnificentFailure.”

More to the point, I’ve always been skeptical about the claims that W/B fabrics perform as they are advertised. Doesn’t it make much more sense that all that sweaty vapor generated by your working body escapes through the neck, cuffs and waist of your coat? I’m not a scientist, but I do know that water always finds the easiest path. I have a hard time believing that water vapor is going to go out of its way to push itself through a dense plastic membrane when it could much more easily escape out of the neck of your jacket.

If that premise is true—that a majority of any shell jacket’s venting will occur through the openings in the neck/cuffs/waist—and I have no way of proving that this premise is or isn’t true (nor, I suspect, does anyone else)—then is there any real difference (beside the price) between a W/B jacket and a coated nylon shell?

Um … perhaps. I actually have experienced the true “joy” of a W/B jacket’s “breathability,” always in the following circumstances: several hours of hard uphill sunny glacier/mountain travel while wearing a zipped-up W/B jacket. In other words, I had to literally all but soak the inside of the jacket with my own sweat before I felt the fabric’s breathability start to kick in.

It begs a question that my shrunken brain was too dehydrated to ask: Why was I even wearing that W/B piece in the first place?

The weight of some behemoth marketing efforts have pushed us heavily toward opting for waterproofness—but in reality, what we as climbers and mountain athletes really need for most situations is breathability.

In recent years, a new breed of breathable, synthetic insulations have emerged that, in my view, are game-changers when it comes how we think about layering for alpine climbing and other mountain adventures. Polartec deserves major props for leading the charge into this new category with Alpha—which I tested (and raved about) last year with the Westcomb Tango Hoody.

But this season, Patagonia has rocked the category with their own proprietary FullRange insulation—which, among a few other subtle differences, seems to be even more breathable than Alpha.

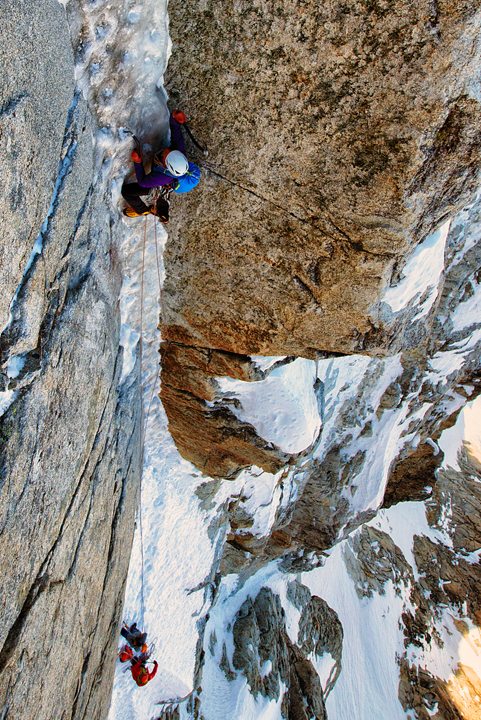

This past spring I had the opportunity to test FullRange insulation in the newly released Patagonia Nano Air Hoody jacket. I brought the Nano Air Hoody rock climbing, ice climbing and skiing in Chamonix, as well as skiing and mountaineering in the Elk mountains of Colorado. I’ve worn it around whisky-soaked campfires in the cold Utah desert, on the sides of big-walls in the Verdon, and I’ve worn it while balling hard around town.

Over these past few globe-trotting months, I’ve changed the way I think about layering for climbing in the mountains.

The Nano Air Hoody, which also can be purchased without the hood, is warm and light (much lighter than fleece, which is a close cousin in terms of performance). It’s extremely breathable. It dries quickly (due to that breathability). It remains warm (due to the fact that it dries so quickly). And most important, it’s comfortable in an impressively wide range of situations—i.e., the Nano Air is cool enough to climb in and warm enough to belay in. Think of FullRange as a performance mid-layer that crosses well into outer layer territory as well.

People used to wear fleece as their mid-layer, with a W/B shell as an outer layer. But in recent years, I’ve noticed a new (disturbing) trend: light down jackets being used as mid-layers underneath W/B shells. Basically, this is the worst of both worlds! No breathability. Little stretch. Easy to lose insulation.

Climbing in the mountains is defined by periods of active performance (the climbing) followed immediately by periods of rest (the belay). You don’t typically climb in downpours, and unless an ice pitch is running wet, you’re often not in danger of getting fully drenched by the elements.

But you will always sweat. What you really need/want is a single piece that can do it all—or at least, perform well enough to do most of it. And breathe really well.

The Nano Air Hoody is the most versatile alpine-climbing jacket that I’ve ever worn. Period. It’s comfortable and stretchy enough to climb in, and breathes well enough to keep me cool and relatively dry even while active. But it’s also insulated and keeps me warm at most belays. Though if I’m really cold, I’ll throw on a big down puffy.

There are limitations to the Nano Air’s performance: namely, it provides nearly no protection against the wind, and despite its DWR coating, it will get wet if you find yourself in that type of situation. (Also, its DWR repellency seems to wash away in the washing machine after several cycles). But even when the Nano Air did get wet, I was blown away by how quickly it dried. One time I wore it up a dripping ice pitch and got fairly soaked. But by the next pitch, the jacket was literally completely dry. Amazing.

The real solution to the Nano Air Hoody’s few limitations is to pair it with a good waterproof layer that you can shove in your pocket and put on at a moment’s notice. I paired my Nano Air Hoody with the Patagonia Alpine Houdini Jacket—a lightweight woven nylon laminate shell with a DWR finish. It’s fully waterproof (10,000mm), packs down to the size of a small orange, and weighs only 6.6 ounces. I kept the Alpine Houdini shoved into the pocket of my Nano Air Hoody, or clipped to the back of my harness, so it’s always nearby and I can throw it on when I need wind protection, or if I’m about to lead up a wet-looking pitch, or even if it starts to rain or snow.

Essentially, I only wore this laminated jacket when I really need it—which was a lot less than my W/B-worshiping brain expected.

There are number of other shell jackets out there that you could pair with the Nano Air as well, some of which are beefier than the Alpine Houdini (I’d recommend the Patagonia M10). But regardless of which waterproof or W/B shell jacket you choose to pair with your Nano Air, expect it to do a lot more time sitting in your pack, clipped to your harness, or stuffed into the pocket of your Nano Air. Trust me, your sweat glands will thank you.

Photos courtesy: Max Turgeon/Patagonia

Thank you for publishing this; it’s great. It’s awesome to see such a prolific source come out and say what endurance athletes of any sort already know: breathability will let you go faster, more comfortably, and avoid that “rainstorm” that you’re so trained to be prepared to avoid.

Really wonderful article, thanks.

Right on, Brody! Thanks for the comment

Here’s the unbridled truth about high tech and the mountains. First, it sounds like a pitch for Patagonia and it’s products, by a Patagonia employee.

Speaking from experience:

Years ago climbers were a pretty tough bunch, who had little money but lots of moxie. They had “silkies” for first layer, wool and down for insulation and heavy coated nylon or canvas as an outer shell. No one complained of weight because that’s all there was. Since then products have come out that have shaved weight off but offer little else in terms of performance. So the bottom line is we now have products that work for the wealthy or well sponsored. Sophisticated marketing

I have to say this read very much like an advert for Patagonia. There’s a time and a place for every type of kit. Without heavy duty waterproofs nobody would survive a typical storm in Scotland, or dare I say it – Patagonia! But I go for breathability over w/p as the priority every time for most day trips with a reasonably reliable weather forecast. And there is plenty good kit around from a wide range of manufacturers, including your local supermarket supplier for climbers on a tight budget.

So if you’re cold, put on more layers. If you’re sweaty then peel off layers or open up pit zips or any other zipper. If your wet or the wind is penetrating then put on a shell. The bottom line now is there are more options, so by all means fork out $400 for insulation, or more for a shell, but know that you don’t have to. Back when my budget was limited I’d buy a first layer for $10, a fleece for $20 and a shell for under $100. As a backup I had a down sweater, a prototype I picked up for minimum coins. I almost never got cold or wet, and if I did it usually didn’t last long or it was no big deal. As a climber I didn’t complain. It was all about the climbing. Besides, I placed more importance on my hardware anyway.

Good point about the waterproofness/breathability of these *-tex jackets. But all these new types of insulation are just as good as a fleece with a wind resistant jacket, like Rab alpine pull-on or Patagonia Houdini. And the latter is more efficient due to layerability.

Agreed. I would say the Nano Air performs like fleece only it’s much better than fleece. That’s the point! Thanks for the comment!

I recently got the BD Access LT Hybrid Hoody and I can say the same thing… The Gore Tex doesn’t even come on most “three season” trips anymore to be honest. Actually breathable, and very warm for most conditions. I’ve been very impressed.

That said, living in the Canadian Rockies… where winter lasts 8.5 months, and “Three seasons” are actually crammed into about 3.5 months, and 90% of my outdoor activities here involves -30C temps, I would likely have died long ago were it not for my Marmot Alpinist Pro Shell. There are many many times when having something to cut the wind is the difference between hypothermia and just being cold.

Breathability is still important so you don’t sweat on the climbs, but that’s where pit zips help out a great deal. The moment I stop moving, the big puff goes on instantly.

Anyways, good post Andrew.

A thoughtful article Andrew, but I think it bears repeating that in my neck of the woods, the wet coast of British Columbia not having a good shell can be a grievous mistake in all but stable weather conditions. I’ve used pretty much every bloody thing thats’ ever passed itself as outwear from logging raincoats to SOTA ptfe rigs and all i know is, wear sunscreen. Opps wrong rant, pick the right tool for the job. For example, days of vigorous touring on the coast in full conditions demand a jacket that does it all; good venting, good breathability of fabric and GREAT DWR -anything less will significantly reduce the fun factor unless you are as hard as Bill Tilman. I’ve seen loads of folks packing it in early on primo days because they cheaped out (or didn’t do their research and believed the hype) thus bailing mid pm due to a sodden mess passing for a shell-whilst meanwhile others merrily shred the slopes in relative comfort. Same goes for coastal alpine climbing-sure you can bite down hard and suffer with a lousy coat in shite weather? God knows we’ve all done that, but wouldn’t you rather greatly reduced discomfort and tap into the psyche of going up rather than letting the excuse of being wet and cold allow the demons on your shoulder to hiss “you really should be prudent and go down, exposure looms”. Now all that said, for fast and light days with little chance of precip I am fully on the program Andrew notes, but lets not huck the DWR baby out with the breathability bathwater!

Thanks. Seems like everyone is jockeying to be next “Goretex” of insulation. I’d love to see some warmth vs weight vs breathability stats on Alpha vs Fullrange vs Ajungilak OTI Climate. Similar to goretex Pro vs active vs event vs neoshell.

I have the Nano Puff hoody and it’s great the only thing is I do wish it has pit zips because being less breathable than the Nano Air, I do have to wash it after big trips to get rid of the smells. Hoping for a nano air for Chrimbus.