I learned how to rock climb in Rifle Mountain Park, Colorado, when I was 12 years old. On my first outdoor lead—Cold Cuts (5.11a), for those who are interested—I completely melted down just five feet from the anchors. I was frozen with fear, and my coach from the gym back in Boulder, my hometown, had to coax me into actually completing the route and climbing the last five feet to the anchors.

Yet … Rifle is also the place where I experienced all those other firsts that go hand in hand with the sport climbing life. Rifle is where I had my first wobbler. It’s where I first learned humility. It’s where I learned to be patient and not rush moves. And it’s where I climbed my first 5.14—Zulu.

Above all, Rifle was the place that shaped me as a youth climber—a period when climbing was all I was and climbing was all that mattered. And to be honest, I struggle, even today, with knowing if anything has changed …

Back as a youth I placed so much importance on my climbing accomplishments. Therefore, my early memories of Rifle are somewhat tumultuous: filled with tears and crushing disappointment along with spikes of joy and relief. Perhaps we all have those special places where we put in a lot of time, battled a lot of adolescent insecurities, and ultimately learned a little bit more about who we are.

For me, Rifle is that place.

Having survived my adolescent years as a climber, I found myself post-college and somewhat jaded and unsatisfied with competition climbing, which had been my main focus in my late teens and early 20s. I was looking for a new challenge, and went back to, where else, Rifle.

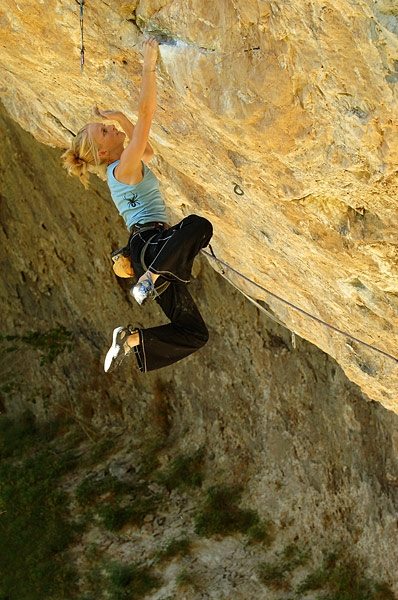

Joe Kinder had just bolted and sent a new 5.14b the previous year called Waka Flocka, and it looked interesting. I started working on it in the summer of 2011. Waka Flocka takes a natural line just left of the infamous Living in Fear (5.13d) on the Project Wall, which is my favorite wall. I love the steep, lengthy oddness of all the routes here. Each one is a puzzle, there are no straight-forward sequences, and there are countless hidden knee-bars where you least expect them. This wall is the epitome of Rifle’s distinctive climbing character.

The first one-third of Waka Flocka contains the hardest moves—including one big, hard crux move in particular. When I first tried the route, I could barely do the bouldery crux sequence as individual moves. It’s all about getting into powerful underclings with very poor feet. The crux involved grabbing a side pull as thin as a credit card and tossing for a flat edge at full wing-span’s distance. But it wasn’t over after that, nor was it easy to get there. There was another hard sequence that involved sticking a tiny edge just a few heartbreaking inches below an enormous jug, which marks the route’s mid-point.

I knew if I could get to that jug from the ground, I could do the route.

As I am a sport climber by nature—a discipline in which finesse and striving for minimal effort often takes you furthest—it took me a while to adopt the mentality of the boulderer, in which you have to give every move 100% effort.

I finally had to accept that the moves on Waka Flocka weren’t ever going to feel easy. There was no trick. I just had to try harder.

After a few weeks of work, I had entered the dreaded phase of “one-hang purgatory.” I could almost climb through the crux, fall at the last move before the rest, lower a few bolts, and climb to the top. Progress wasn’t halted, but it had slowed. I’d feel incrementally stronger every time I tried, but never strong enough to complete the whole boulder problem from the ground. It became a mental game. I could hear the clock ticking. The canyon was getting colder, the season would be over soon. I began to feel pressure, wanting so badly to experience the satisfaction of sending.

Then the crux holds of the route began to seep. The wetness was inconveniently occurring on the two flat underclings where the hardest climbing began. There was no way to stop and chalk, so my hands remained wet throughout the most difficult climbing. A couple times during working burns my hands would just ping off the small crimps without warning. It frustrated me immensely, and I found myself laying awake at night, anxious over whether a few inches of rock would be wet, and just how wet.

After nearly 40 days of trying Waka Flocka, I was getting tired of doing the same moves. I felt disappointed and angry at myself. It’s absurd, of course, I know. All that emotional turmoil and stress over a stupid piece of rock. But I cared. It was important to me, and I couldn’t help that. I felt as though I’d reverted to that adolescent phase again, in which I was letting 100 feet of limestone—named after some silly hip-hop sensation, nonetheless—define my self-worth and happiness.

Toward the end of October, after a season of one-hangs and failures, I drove into the canyon one more time. The temperature was frigid and the season felt over at that point, but I wanted to try again. I wanted to succeed so badly and be … free.

I warmed up on the route by pulling on the quickdraws, and getting up to the wet crux holds. Using a dishwashing rag, I padded the holds, drying them as best I could. They seemed damper than ever.

The day I sent Waka Flocka, I climbed nervous and stiff. I slipped and fell lower than normal, and proceeded to have a complete freak-out.

“I’m sick of this!” I screamed. I thought I should just give up. I told myself I can’t do it. I told myself I hated this. I promised I wouldn’t do it. I said every negative thing I could think of. Anger and frustration poured out of me.

Then I felt embarrassed, immature, and emotionally drained. Why did I get so angry over something so trivial? I had placed so much significance on this one route, and couldn’t let it go. After I’d calmed down a bit, I felt relieved. My little temper tantrum seemed to help. I’d finally surrendered to the idea of failure. I had nothing left to give, and that was ok.

I decided to give it one more shot, for no other reason than to simply try.

I now felt more relaxed and level-headed. I put my kneepads on, cleaned my shoes, and tied in. I climbed up to the crux. I felt a bit fatigued, but didn’t care. I just let my body take over, trusting it to execute moves it had practiced nearly 100 times at that point.

When I reached the move I’d been falling on repeatedly, somehow, I don’t know how, but I stuck it. I had felt weaker than before, but somehow I just grabbed it … and I found myself at the midpoint rest. My nerves returned in a flash flood. I couldn’t blow it now, I’d be crushed. I finally summoned the courage to leave the rest, and climbed swiftly and without hesitation. I had to fight hard to get a kneebar, then stay composed and keep it together through the vertical section leading to the chains. But … I did it. I lowered down from sending my hardest route to date.

I didn’t know it at the time, but that would be my last climb in Rifle for a very long time. I didn’t return the following season. Instead, a twist of fate and luck gave me the opportunity to climb Mt. Everest. Life changed after that trip. I moved to California and sought out a different sort of satisfaction from climbing. I swapped limestone for granite, bolts for cams, and 5.14 for 5.10. I went from elite-level sport climbing to gumby trad climbing and learning the basics. Even with trad climbing, I found myself getting upset for failing, for being afraid to fall again. The feelings I had on Cold Cuts at age 11 returned at age 26 on One Hand Clapping (5.9) at Donner Summit, and countless others.

I began to wonder if maybe that’s just the way climbing is, no matter what the grade or discipline. And maybe that’s the way climbing ought to be, too.

Normally, a big redpoint like Waka Flocka often leads to a big realization or lesson. But this time, it wasn’t till over a year later that I think I learned something from my experience with Waka Flocka.

What I’ve realized is that there are no answers on summits—whether that’s the top of Mt. Everest, or at the chains of a redpoint of a 5.14b like Waka Flocka. Climbing isn’t about the success, or even the failure. But rather all the in-betweens. It’s about the process of facing yourself and seeing a beginner who’s willing and psyched to keep learning. What I’ve realized is that climbing, like life, never comes easy. And deep down, I think that’s why I keep trying.

Awesome story and an interesting accomplishment!

I always love your stories, Emily. Thank you for keeping it real, you are the shizznit!