“I want to lad The Evictor,” I told Nick, arriving home after a spectacular, sun-drenched winter day at the Rincon Wall in Eldorado Canyon.

I had successfully—and quite easily I might add—top-roped The Evictor (5.12+ R), perhaps the canyon’s most famous single-pitch test piece. I am fairly sure that Nick, my now husband, mumbled some scaled-back version of encouragement. He was well aware that I had not yet led the warm-ups at the Rincon Wall, and that I was often paralyzed with debilitating fear while top-roping. But my enthusiasm would not be tempered; if learning to place gear and run it out were the requisite skills I needed to succeed on this route, then I set myself to their acquisition.

I started climbing in the gym during my final year of college as a means of facing my debilitating fear of heights. Yes, I know that virtually every one is afraid of heights; it is evolutionary and instinctual. You should be afraid of heights.

My fear of heights, however, was much more extreme than your average cookie-cutter brand of acrophobia. Over the years I’ve been hospitalized from vertigo-induced panic attacks and once had to be “rescued” from the center of a suspension bridge when I passed out while walking across. My fear of heights is not hyperbole and I feel confident surmising that it is likely worse than yours.

Ironically, I loved climbing immediately. The movement, the grace, the combination of the delicate and the gymnastic. But what affected me most was the intentional experience of exposing myself to fear. The first time I climbed a route, I was paralyzed halfway up and had to retreat to recover. The next time, perhaps emboldened by the realization that neither my partner nor the anchor was assuredly going to kill me, I climbed to the top. I still experienced the fear, but in climbing I had found a medium that allowed me to systematically and methodically face it. The ability to quickly whittle down a problem and perform despite a pronounced inclination to do the opposite was revelatory.

When I decided upon The Evictor, I had only been climbing a few years, and the majority of this time had been spent sport climbing. I had been working my way through the grades, alternately navigating the challenges of projecting 5.12 and dealing with the waves of fear-induced vertigo that often obscured success on these routes. Some days I had to relegate myself to top-rope only. But I was determined to be a rock climber, dammit! And despite frequent experiences of discomfort, I had fallen devastatingly in love with the sport.

To climb The Evictor, I needed to learn to place gear, and so I practiced the intricate placements on top-rope; Nick followed to assure that I understood the basic mechanics. I climbed the insecure and poorly-protected start dozens of times; I even pink-pointed the route to get the feel for the run-outs without the stress of placing gear.

Eventually the day came when I took the rack and headed up on lead. I climbed the final pumpy moves, fifteen feet above a #5 Stopper. When I grabbed the summit jug, Nick whooped loudly from the ground. I lowered off, psyched, overwhelmed, and, above all, bewildered by the complete absence of fear I had experienced.

The Evictor taught me a lot about my personal relationship with climbing; about how to embrace fear by seeking out the experiences, people and places that make me uncomfortable. To make the process of challenging myself a constant in my life, and to let myself be drawn into that which inspires me regardless of how ambitious or outlandish it might initially seem.

In years after The Evictor, climbing became central to my world—and seeking out routes that challenged me in similar ways became a driving force in my life.

I found myself drawn to scary routes, to instances requiring bold decisions with major consequences. At first I was essentially recreating my experience with The Evictor. In time I found myself venturing out into unknown territory. Routes in the mountains, routes with ground-fall potential. The problem with intrinsic, natural fear, however, is that it is nearly impossible to rid yourself of it entirely. Was I seeking routes that offered ample opportunity to overcome fear because it was how I learned to climb, or was it a continuation of some deeply masochistic effort to push myself toward a breaking point?

As I systematically worked my way through other Eldo scare-fests, I was reminded repeatedly that I had not, in fact, turned into a bold climber. I had simply taught myself to manage the stressors and outside factors that might affect my ability to perform.

My fear of death-by-way-of-falling was as much a part of me as my right-handedness. And no matter how much time I spent trying to learn to write with the left, when handed a pencil I am always going to instinctually take it with my right.

These realizations offered me numerous lessons in humility and an ever-evolving appreciation for the personal significance (and obscurity) of climbing.

These realizations offered me numerous lessons in humility and an ever-evolving appreciation for the personal significance (and obscurity) of climbing.

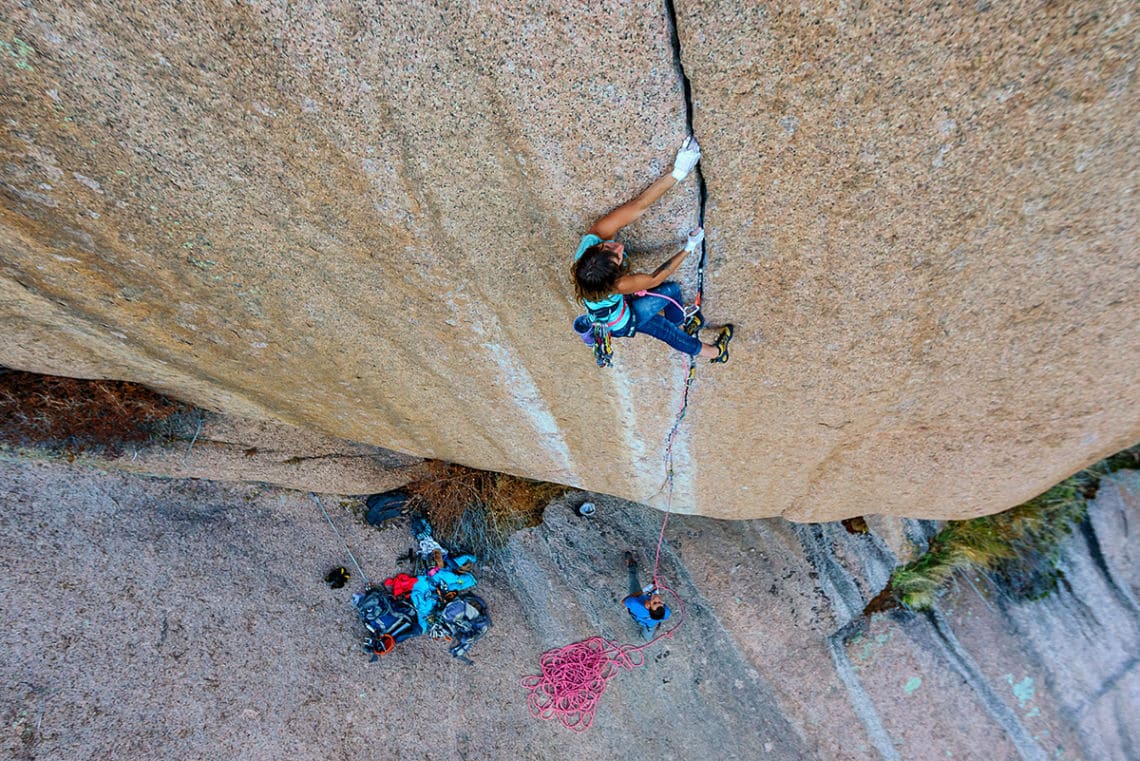

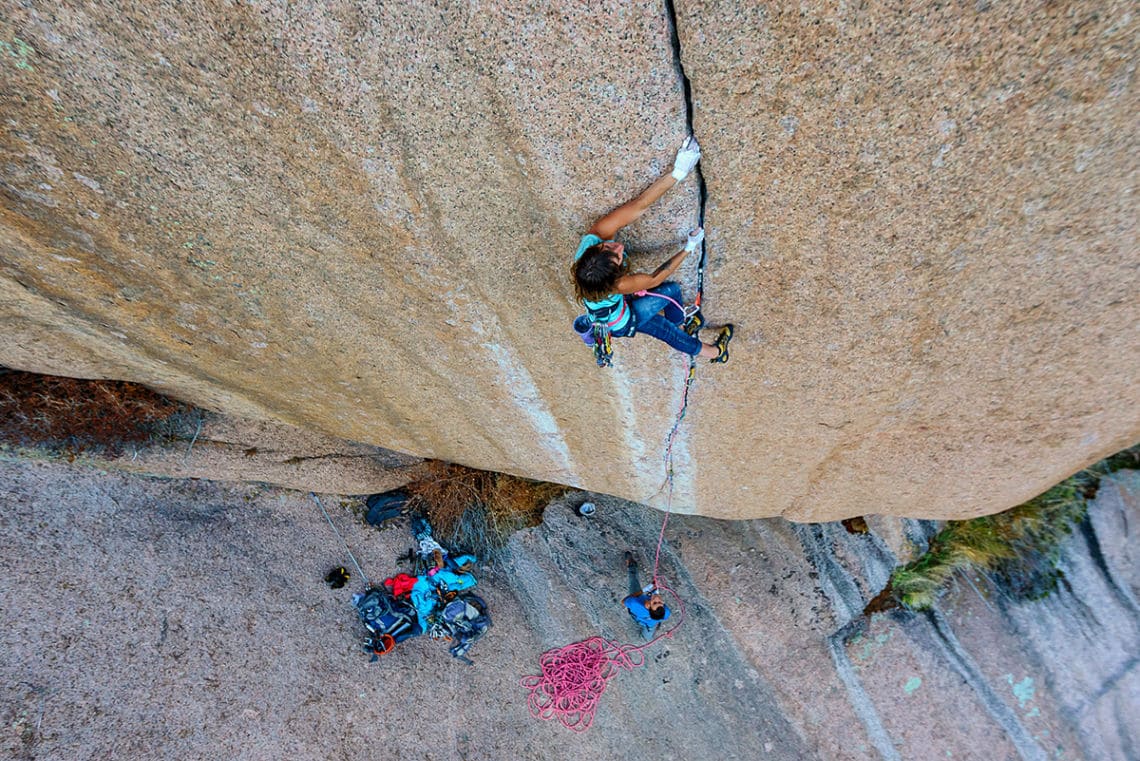

The first day that I climbed on Skinny Love (5.13c)—sometime in the Fall of 2011, I believe—was particularly uninspiring. I was not looking for a project, but had seen photos of my friend Jason Haas—the prolific first ascentionist, and guidebook author—on the route. Immediately I was drawn to the crack’s aesthetics: a distinctive line bisecting a singular block of golden granite deep in the maze of South Platte’s iconic outcroppings. A solitary route in a not-often-traveled part of the canyon.

Day one: I doubt I linked more than two moves in a row.

The route begins as a faint seam (just within reach as you stand on the ground), then gives way to barely-there edges, then tips, then finally opens just enough to allow your fingers to almost lock in. Here you must pause to place a #00 Master Cam, the only thing keeping you off the ground, while your feet skate and your bicep trembles, engaging in what I came to refer to as the “death-lock-off.”

Just to reach this point involves a difficult, subtle and finicky boulder problem. While I am a particularly unimpressive boulderer—due to my aversion for both hitting the ground and being dynamic—being a trad climber trained on Eldorado stone has taught me to feel comfortable with subtle, finicky moves. I am drawn to climbing that is more psychological and technical than gymnastic, and this boulder problem was just that.

Still, it took me nearly three days of work just to figure out how to pull myself off the ground. In an outrageously frustrating manner, Skinny Love shut me down before my second foot ever connected with the stone.

Once established on the wall, I faced a series of precise, long moves with feet pasted on subtle undulations in the slabby granite.

Following the boulder problem is what I consider to be the crux of the route: a handful of moves of 5.12+ finger crack. Despite being a self-proclaimed trad-climber, I am not very good at pure crack climbing. This was bound to become the crux for me.

I was intrigued from day one, though it took a number of subsequent seasons, each with a handful of days effort, before I even believed the route was within my ability. Skinny Love was not only at my limits of my physical performance but it was simultaneously testing my climbing weaknesses.

In addition, with a short season, all-day sun and winter road closures, there were a multitude of sheer logistical factors working against me ever sending the route. But I had fallen in love with the climb. Like The Evictor, Skinny Love was inspiring me to become better. To work diligently on my weaknesses, to dedicate myself to something that I might fail on, to challenge myself because I was inspired to do so.

During this time, however, I found myself climbing less. I had spent nearly a decade with climbing the epicenter of my life, my identity, and my time. I was growing out of the fear of getting weak if I lost a week to another pursuit, and in its place I was finding value in challenging myself in new ways and doing new things.

At this point, Boulder had become home and its community of once-road-bound climbers, my family. I was enjoying long days on the moderates of Eldo with friends, learning and becoming competent with new skills (such as an ill-advised fall season spent off-width climbing), relishing the lack of hard projects and the requisite obsession that goes with them. I was having fun and climbing regularly, but had likely not sent 5.13 in a year or so.

An amazing attribute of climbing as a lifestyle is that it is adaptive and responsive. Climbing becomes what you need it to be. As Nick and I began to make tentative plans to move on from Boulder, I wondered if my love for climbing was vacillating, if the fire was slowly extinguishing itself. I wondered if I needed a new type of challenge.

When I was accepted to graduate school in Boston, that potential change suddenly became very real. And suddenly I realized how much I wanted to climb Skinny Love.

I had worked on Skinny Love for three seasons, typically getting shut down by the road-closures and weather just as I was confident that I was near sending. The fact that I was about to move far away set in, almost as a type of panic that I might find myself three weeks into school and regretting that I hadn’t given Skinny Love my all.

As I was picking out classes and packing boxes, I also began to drive at sunrise from Boulder down to the South Platte to Mini Traxion Skinny Love.

After a month spent climbing long moderates in Yosemite, the once-doable boulder problem now felt impossible to me. Ironically, I was climbing the section of 5.12+ finger crack with relative ease. Go figure. I was simultaneously re-inspired and fearful of my time constraint due to our move. Part of the reason that I loved this route so much was its lack of urgency; how it had always just been there; how I knew I would do it when I was ready.

Now, there was fear. I was scared that I would fail and would have to leave Boulder defeated by a multi-year project. Scared that my love for climbing had changed and was, in some way, less valuable in its new form. Scared to leave Boulder, our family, and our lifestyle behind.

Somehow all of these fears had become wrapped up in this one rock climb. This objectively insignificant piece of granite had become this monumental personal symbol of so much more.

Last June, I decided that I absolutely needed to send Skinny Love before we moved. I committed myself to this goal, likely a coping mechanism for huge life changes closing in on me and a reflexive need for a familiar experience. I was focused and intent, Mini Traxioning on the route in the morning and training in the gym in the afternoon.

Before long I could do the boulder problem again.

I convinced my friend Mike O’Connell that he needed to do this rock climb, too. The oldest trick in the book, but at least I had a partner willing to drive from Boulder to the South Platte at dawn, and be ready to give Skinny Love an effort by 8 AM, the beginning of a four-hour summer temperature window.

Mike and I were committed. We drove four hours each day for less than that amount of time spent of rock climbing.

As moving day quickly approached, I found myself one or two moves away from success.

The most fundamental reason that I love climbing lies in the lessons it has taught me; to love and respect our natural places, to live wildly, sometimes unconventionally, and with abandon, and to constantly seek ways to challenge myself and what I am capable of. As trite as it may sound, it is these lessons that have given me the gumption to make bold decisions outside of my climbing life.

I have experienced paralyzing fear in the face of uncertainty, and I have learned that a methodical confidence and sense of purpose define what one is capable of. I spent nearly a decade of my life letting climbing teach me about the person that I wanted to be and the life I wanted to live. And part of the appeal of climbing is its objective insignificance; its value derives wholly from the experience of the individual. Climbing is literally what you make of it.

The day I sent Skinny Love was the last day before I moved away from Boulder. When we arrived at the route that morning—having driven through beautiful summer sunrise to a temperature below 60 degrees—I was immediately crippled with fear. I had packed so much meaning into a single 60-foot pitch and I was suddenly very aware of the immediacy of my predicament. The difficult-to-place gear and crumbling rock posed such a mild threat compared to the debilitating fear of failure that was pumping through my veins.

Incredibly, in Skinny Love I had found a fear greater than my fear of heights: a fear of failure and regret.

Visibly shaken, I turned to my climbing partners for reassurance. Thirty minutes of climbing pep talk and familiar motions. Mindless chatter and the repetitive practice of taping, stretching, and racking up.

Meditative moments in which I executed, as I had so many times over the years, the practice of subduing my own fear.

Rehearse beta, tie in, tell myself that I am, in fact, bold and strong and not the least bit scared.

And then … climb.

The day I sent Skinny Love was three years after I first set eyes on the route. It was exactly one month before I would begin an intensive graduate program that would render climbing a cherished outlet necessary to maintain perspective but no longer the sole reason for being.

Again, climbing becomes what you need it to be. You can abandon it from time to time, but it will never abandon you.

Skinny Love remains a faint, rarely seen crack in an obscure granite block lost in the South Platte of Colorado. But to me it is a symbol of change and a reminder to remember why we do the things we do. It reminds me to appreciate the simplified process of interacting with the world around me, to embrace change and to honor humility. Above all, Skinny Love affirms the potential in myself to face fear and uncertainty, and to remember that that process is something to be grateful for.

Wow great story Jenn.

I loved this story, it was really inspiring!

Thanks for sharing. Great story and very inspiring. Very nice photography.

Thank you for writing this inspiring article. I really identify with your approach to climbing. (my subjective reality is objective to me!). Psyched to head back for some great learning on colorado rock this spring!

Amazing amazing amazing. Such a great story. What you wrote about climbing abandoning you really resonated with me. Best of luck at grad school.

Thanks for writing this! With that kind of attitude, I’m sure your program will be successful. It sounds inspiring as well.

Fantastic. Beautifully written and the video is wonderful. Hope your grad school is going well.