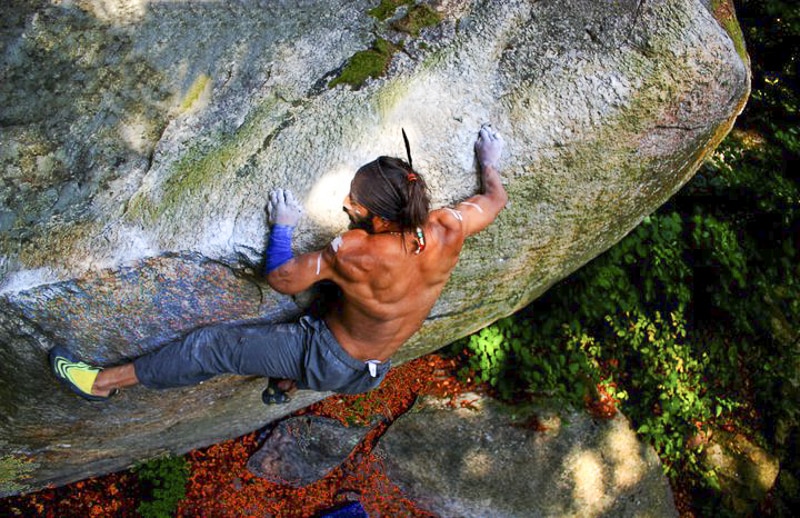

Climbers like to nitpick how our relatively slight variations in body size and shape lend themselves to drastic differences in grades. “Oh, you have a +2 Ape Index, but I’m a -1 so that V5 is at least V6 for me.” But for Philippe Ribiere climbing isn’t just harder, it should actually be impossible. And now, he has the scientific evidence to prove it.

Philippe Ribiere was born with a variation of Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. Recently, a couple of researchers from the School of Sport Sciences & Technology at Hacettepe University in Ankara, Turkey, and the Institute of Movement Sciences at Aix-Marseille University in Marseille, France, teamed up to study and quantify the consequences of Philippe’s disabilities on his grip performance, and investigate finger-grip capacities of disabled climbers in general.

What they discovered was, first, that Philippe Ribiere clearly has less maximal finger force than other climbers, with deficits ranging from -21% for large holds and nearly -40% for small holds. He also has a lower profile of finger friction between skin and hold.

According to researches Arif Mithat and Laurent Vigouroux: “Philippe compensates his lack of maximal finger strength by using the passive structures of the human body more than other climbers and he has extraordinary grip techniques which are rarely used by other climbers.”

In other words, Philippe Ribiere is able to overcome his disability through technique (a concept that supports the premise it’s better to get good than it is to get strong)—grabbing holds in such a way that he relies on his skeletal frame, more that musculature, for support.

Mithat and Vigouroux continue: “Since he has unique hands, his muscle trajectories and joint mobility’s are unknown. Therefore, it is probable that other muscles are involved to the contractions in a special way. This theory also contributes to the explanation of his successful resistance to fatigue. His impressive performance is not only due to muscle fatigue of the finger flexors but also to other compensating muscles.”

I met Philippe Ribiere in Getu, China, at the Petzl RocTrip in 2011. Philippe has been a staple of the Petzl Team since 2002. On a rest day, we decided to explore the lower arch/cave, an enormous chamber accessible only by boat. Philippe and I loaded into a small two-person inflatable raft, each armed with a flimsy plastic paddle. Within moments, however, Philippe accidentally dropped his paddle and it sunk into the milky green current of the Getu river.

“Well … this will now be a nice adventure,” he said. He was apologetic for dropping the oar, but it also clearly wasn’t going to ruin his day.

We continued paddling into the cave and arrived at a landing zone, where Philippe scrambled out of the boat. We reached shored and entered a maze of erratic boulders. Now I saw a guy who felt much more at home scrambling up and around the rocks.

Later that night, there was large party in the center of town, and Philippe stole the show with his fire juggling performance.

Born on the French Caribbean island of Martinique and abandoned by his parents at birth, Philippe was later adopted and brought to France. He first discovered the vertical world at age 6 during a vacation to St. Gervais with his adoptive family. Their first task was to rappel off a cliff, and Philippe remembers being scared that he’d be able to even hold onto the rope. (The instructor rigged a back-up). Philippe was terrified of the exposure but when he finally committed to rappelling, he remembers being happy and proud to have been able to do the same thing as his brothers and sisters.

By climbing on teams and in the gym, Philippe Ribiere fell in the love with the sport and eventually would go on to place in the finals of a junior championship in his local gym. Today Philippe can be called a pioneer of para-climbing competition. In 2000, he met with the ICC and UIAA to allow demonstrations with handicapped climbers during the European Championships in 2002 and the World championships in 2003. That year, he founded Handi-Grimpe association, and its first event took place at a gym in Gard, France.

In 2011 Philippe took the bronze medal for speed climbing at the first para-climbing World Cup in Arco.

“Climbing gives me confidence, feeling in my arms and legs and the simple pleasure of being outside,” says Philippe. “Climbing fulfills my need for commitment. Climbing gives my life a purpose. Climbing allows me as an individual to reach a certain social level, to meet the best climbers, to organize events for people of reduced mobility thanks to Handi-grimpe and the Evolution Tour.”

I caught up with Philippe Ribiere this spring to hear more about his past and what’s next for climbing’s biggest little man.

What is the story behind this study?

We did this as research for the “Wild One” film to learn more about how my body reacts when I climb.

In 2008 I returned to Martinique to meet the first doctor who repaired my wrists, arms and feet when I was an infant. He explained that they fixed my wrists because they always came back inwards. It was a problem because I can’t hold onto various objects in everyday life. If I understood correctly I don’t have working extensor muscles. Basically, through the study I learned I have 20 percent of a normal strength of a human.

When I got this information I changed my mind about some possibilities.

Now when I train, my Slovenian friend, Urh, has been better able to help me push through my weakness. For example, with my right hand I had been using my thumb wrapped by my fingers to take the crimps. But now I climb with open hands, semi-arched.

I am getting stronger for rock and also for competition.

How do you define the challenges you face?

I am different already by the fact that we are all born different. But it is true that my difference is called “handicap person.” The climbing community has opened doors for me to confront my fears and worries through this sport. But also, climbing reminds me that I am the only one responsible about my actions. If you don’t place your feet on the hold well, you will fall.

To really talk about my differences, I have short arms, with no flexible wrists and deformed fingers. What does it means? For instance on the rock I can’t really use underclings, unless they are already at my waist level.

I don’t have strength in my forearms to pull. When I climb I take the hold and push down. If it is undercling I push up. If it is a vertical hold I push on the sides.

The difference between a normal climber and me comes down to the fact that most climbers grab holds and are able to tighten down and squeeze them. But I can’t do that. It is maybe hard to understand what my condition means, but we are all in the same situation. We all have to climb with the body that our mother and miss nature gave us. I can’t change who I am but I can try to train my weaknesses.

What type of climbing do you prefer?

Today my main activity is sport climbing with a preference for bouldering. Since 2000, I knew that my friends have a family and a job, so finding a belayer during the week was hard. Naturally I went bouldering, which is the best compromise.

Also I had an accident in 2002 climbing on a rope. My friend/belayer was not paying attention and he had 2 meters of rope on the floor. Well I was almost at the top of the crag, clipping a quick draw and a hold broke. I fell for quite a long time! I saw the rock near my face and BOOM, it hit me in the face. It was like a horror movie, with blood everywhere. And I broke my ankle.

After many travels around the world over these last 10 years, I just prefer to climb without thoughts for the grade and to climb/boulder onsight.

How many countries have you visited for climbing?

Enough countries to be the happiest man! I never count how many I did. I just know I am a traveler for 18 years since I started the climbing. I do remember for sure the first international trip in Gunks with the Petzl Team in 2003. I’ve been to England, Greece, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, almost all the Eastern Europe, Canada, India, China, Japan, Mexico, Argentina, South Africa, Scandinavia, and Mallorca.

What are your interests outside of climbing?

I love to edit climbing movies and some short art movies that I never translated into English. I was also a reggae singer for two years in France. I also do some fire juggling because I love the connection between the fire and me.

My handicap difference is an asset for some photographers and filmmakers who ask me sometime to participate in art movies. For myself it is kind of revenge—even I don’t like this word—because I believe even the ugly things can be nice things. So then I use my face, my body and my handicap as an art and I love it.

What is your role in the world of para-climbing competition?

I am 37 years old and I was born in Caraibes on the island of Martinique. I have no job right now during the last 20 years because I am a rock climber.

Even it is not an official job, I became the pioneer about the creation of the para-climbing category. I also dressed the first handicap event in France to encourage other para-climbers to show up themselves. I’ve always known the international federations have wanted to be in the Olympic games and for sure to be accepted on the short list, the sport needed a Paralympic category.

I did it for many reasons and I am proud of it. I am really glad that now we have so many para-climbers who come to compete. It is really awesome to see.

How did you start climbing and what keeps you coming back?

I have been climbing for 20 years. I started in 1994 during the summer holidays in France. After the first experience in this camp, I went to my hometown to register in the climbing gym.

Like all climbers, I got addicted to this amazing sport. I mean this sport mixes the force, the motivation, the pleasure to be outside with a couple of friends and this is it. I can’t really imagine my life without this passion. Climbing is my lifestyle. It embodies my life philosophy: Be free.

Great article, Philippe is super inspiring, thanks!