Nearly penniless, I pulled into Austin, Texas, during the early days of March 1997 with a plan to make some quick cash. I was going to do something I thought I’d never do. I was going to sell my body to science.

The plan, hatched 500 miles away in Hueco Pete’s parking lot, had first formed when two climbers returned from Austin with tales of easy money but with one rather significant catch.

“We were lab rats, dude!”

When I first heard their tale I had thought, “No freaking way! Not in a million years!” I had too much dignity. It seemed so degrading—not to mention unhealthy. I mean, how do you even know what drugs they’re giving you?

But with the fires of ambition running out of tinder, I faced the hard reality that I was too much of a dirtbag to give up my climbing lifestyle and get a real job. Concessions had to be made. We all have our price and it turns out that I would be a lab rat for $1,000 and eight days of “work.” It seemed like a fair deal when faced with the alternative: drifting back to Nashville on fumes and a pocket of unspent climbing dreams.

The suburbs of Nashville in the 1970s were a perfectly safe and largely uneventful place to be raised. I could’ve done much worse, but it was also boring as hell. My truck-driving father made a decent wage, but it wasn’t ever enough to go on vacation or travel around much. As a result I daydreamed of far-off lands more exciting than humdrum middle Tennessee.

When I discovered rock climbing in college, I found the perfect outlet for adventure and exploration. I was immediately obsessed. My lackluster athletic record was something that always gnawed at me as well. I had performed at a high level of mediocrity at sports ranging from baseball to track, wrestling to rowing. In that post-collegiate space of failed experiments in traditional athletics, I had something to prove. Right from the start I wanted to climb hard. I wanted to climb bold. Those were maybe the first two things that were ever important to me.

I soon discovered that becoming a lab rat wasn’t as easy you might think. Blood types need to line up. Heights and weights need to conform to test requirements. Emotional states need to get clearance. It turned out I had driven 500 miles away from my beloved boulders of Hueco with no guarantee. I spent the next few days loafing around Austin, waiting to hear if I made it into the study.

I made friends with another hopeful lab rat and climber, Kerry Allen, who was from Arkansas. We made camp in the parking lot of a voodoo bike shop off Guadalupe Drive somewhere in the middle of Austin. We burned tall votive Jesus candles for warmth in a 50-gallon barrel at night and shivered.

Kerry sported a rather unsightly mohawk and perhaps gave less of a fuck than any one person I had met in my life. On the rock he was fierce and tenacious and what he lacked in talent or athleticism he made up for with boldness, and a never-let-go attitude.

A random emo dude dressed up like Brandon Lee from The Crow joined us around the “fire.” He baffled us with talk of crack climbing in the Wind River Range as we drank beer. Things got weird when he told us he sensed some hostility in us. Kerry and I told him to leave.

By day I bouldered a couple of sessions at the Ped and E-Rock. One time I watched the Austin Energy Plant mysteriously blow up and burn while I spoke with my mother in a phone booth. It was all quite surreal.

Eventually Kerry and I got in. Fifty applicants and only 8 were admitted and I was one of them. Lucky me. For the next 8 days I would be administered Ketoprofen in patch form. I would be dosed 3-4 times. Blood would be drawn 15 minutes before each dose, one minute before each dose, one minute and after, and then again, every hour on the hour (even in the middle of the night) until the dose was found to have worn off. Our diet was strict. Eat no more and no less than what you are given. Our clothing was assigned. It was a bit like being in prison, I imagined. Under no circumstances could you leave the facility before the test was completed. Disobey the rules and pack your bags, no pay. It was all or nothing. Aside from the blood-drawings, the eight days passed relatively quickly. Oddly enough I had a TMJ infection at the time, and the Ketoprofen made the pain in my jaw go away. I guess the patch worked.

I couldn’t say the same for Kerry. His study was for a morphine derivative with terrible side effects. Mostly sequestered to a separate section of lab I would only occasionally see Kerry sprawled out on a gurney, nauseous and green from the drugs. Meanwhile I played pool and watched movies, pain free.

I collected my $1,000 check, cashed it, and hit the road for Vegas. At my first casino buffet I filled a haul bag with cookies, bread, and anything else I thought might survive being smuggled out. I drove toward Red Rock. In those days you could camp for free across from the Gypsum mine. BLM even supplied potable water and a portajohn.

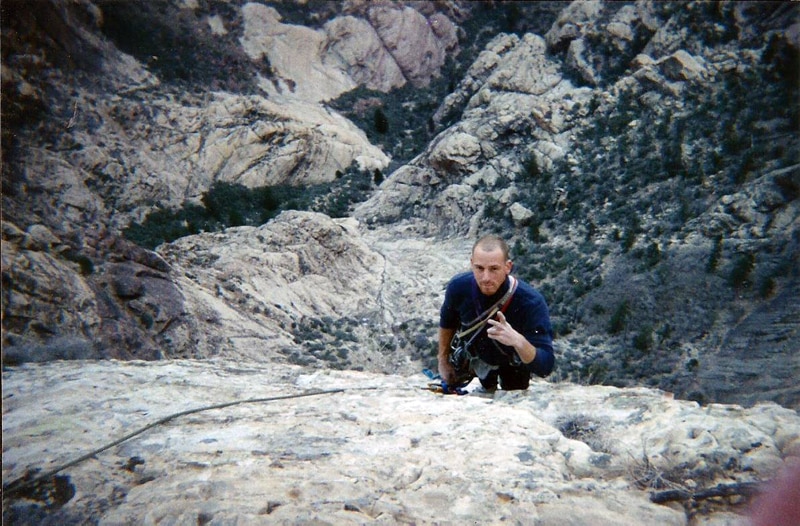

This was my first visit to Red Rock and I felt such a relief to be there. Three months of bouldering at Hueco Tanks was fun, but the grind of bouldering day after day and living in the stark West Texas desert can make even the most hardcore climber weary. Bouldering hadn’t exactly prepared me for the long routes up Red Rock’s canyon walls, but I did have some power. What I needed was endurance and to get out on the sharp end.

Ambition was merely a seed but it would grow in this most pivotal spring of my life. Slowly but surely long routes got ticked. Frogland, Fiddler on the Roof, Epinephrine, Levitation 29, Cloud Tower, Rainbow Wall. My newfound Hueco power proved to be an asset on the long endurance sections at Red Rock. No moves could stop me. I gained confidence. That confidence fertilized that seed of ambition, and what ended up growing was ego and the need to prove to myself that I could do something that would measure up to my climbing-heroes’ accomplishments.

I came up with a goal that seemed just difficult enough to be spray worthy, but not so difficult that I might fail. Simul-climb Crimson Chrysalis, Cloud Tower, and Epinephrine in a day. All free, no falls or the venture was a failure. Every since I first started climbing I was enamored with Peter Croft, John Bachar and the Yosemite idea of linking massive features in a single day of speed climbing.

I knew deep down in my plums that I could pull it off. Whether someone else had done this particular link-up or not, I didn’t know.

But it would surely be the most difficult thing I’d ever attempted in climbing. I needed the right partner and oddly enough, Kerry, my friend from the lab, had also arrived in Red Rock that week. He had escaped selling his body to science with his bodily functions intact.

He was game for the adventure. Preparations were made and logistics were organized.

The date for our link up was set for April 1st, 1997, which I would soon come to find out was a day of great astrological importance.

As a kid I was always excited about astronomy. Mostly I just liked staring up at the stars and dreaming about nothing in particular. I read books by Carl Sagan and Steven Hawking, not having any idea what the hell they were really talking about. But I was fascinated by one of Sagan’s stories about Haley’s Comet, in which he described how the comet had affected unsuspecting people in mysterious, even superstitious ways.

Around the time I was planning to do my Red Rock link-up, there were news reports that a comet named Hale-Bopp would be swinging by Earth for a visit, and the day for optimal viewing would be April 1. I didn’t think too much of it. I didn’t know whether I’d have any possibility of actually seeing it. What if it was cloudy? More than anything, Hale-Bopp just didn’t have the same ring to it as Halley’s Comet. Besides, my thoughts were focused on the link-up.

The day before the link-up, I slept in. I was cooking breakfast on the tailgate of my Ford Ranger when Kerry rolled in to the parking lot. He hopped out of his Nissan looking wild eyed and spun.

“Where have you been?” I asked

“Oh, I just soloed Epinephrine,” he said.

What?!?

“Solo? That’s great dude, but …” I looked at him blankly. “What about the link up? Aren’t you going to be tired?”

Kerry explained that he was drawn to solo Epinephrine and just couldn’t stop himself.

“Don’t worry, dude,” he said. “I’ll be fine for tomorrow. Nothing to worry about.”

I couldn’t believe it. Why now? Wasn’t the link-up more important? More badass? Admittedly, this was my ambition—not his. But, he was the only partner I knew who was remotely up to the challenge.

I had to hope he would be ready.

That night we drove into the loop road and camped in the parking lot for the Cloud Tower. The sky was clear and Vegas glowed warmly on the horizon but I remember a distinct chill in the air. I slept on the ground and woke a couple hours before first light to see the twin-tailed celestial apparition of Hale-Bopp, streaking low across the sky. I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was magnificent. This was easily the most spectacular wonder I’d ever seen.

The morning was something beyond still. The quiet of the desert can often seem like there’s a roar in your head, it’s so intense, but not this morning. The stillness was absolute. The comet seemed to have some sort of muting effect. It was hard to relinquish my gaze of the comet as I finalized my pack for the day.

We began by onsight simul-climbing Crimson Chrysalis. The bolts flew by as we made our way up the route in two pitches and only stopped to re-rack at the midway point. We simul-rapped the tower as the sun started to light up the canyons. The Neapolitan dunes of the Calico Hills shone back as Hale-Bopp disappeared over the horizon.

We dashed up the first moderate pitches of Cloud Tower in growing daylight. My confidence grew as pitch after pitch went by. I casually dispatched the fingertip crux corner and offwidth pitches, setting up my partner to lead the pumpy Indian Creek-style endurance corner capping the route. Kerry stared up at the red corner.

”Sorry, man,” he said. “I’m gassed. You’re gonna have to lead this one.”

I grabbed the rack and tore ass up the corner. I clipped the chains and called out that he was on belay.

“Just rap!” he shouted back. “I’m toast!”

I set up the rap and descended, feeling my dreams slip away like a comet over the horizon.

We started our rappels.

“There’s no way you can do Epinephrine?” I asked. “I’ll lead the whole thing.”

“Dude, there’s no way. I’m wasted.”

Things had been going so well and I wasn’t even tired. Hell, I felt like I was just starting to hit my stride. We didn’t speak a word to each other during the rest of the descent. I wasn’t mad, just kind of dumbfounded and disappointed by the whole thing. Why had Kerry needed to solo Epinephrine yesterday?

By the time my feet touched the ground I realized that I wasn’t finished. I saw the opportunity I had been granted. I would have to really earn this one—like Croft and Bachar and all my other climbing heroes. Blinded by ambition, I only knew that if I wanted to finish the link-up, I’d have to climb Epinephrine on my own.

“I’ll solo it,” I said.

“Are you sure?” Kerry asked?

“Yeah, I think I’m sure.”

I hadn’t imagined soloing Epinephrine but, earlier that spring, Kerry and I had simul-climbed it together onsight and I felt solid. Of course, I had also heard a rumor that Peter Croft tried to solo Epinephrine, he reached the 5.9 roof move 1,500 feet off the deck, got spooked, turned around and down-climbed the whole thing back to the ground. To this day I still don’t know if its true about Croft backing off the final roof move. I seriously doubt it. My god, it would be way more difficult and amazing to down climb all the way back from that point.

For me, the roof move had felt solid with a rope … But would it feel solid at the end of a long day of climbing with nothing but air beneath my feet?

I guess I was going to find out.

I sped over to Black Velvet Canyon and hiked up the trail completely transfixed. Mine was the only car in the parking lot and I was thankful for that. I’d be all alone with no distractions. I started up the initial chimneys, moving carefully and pressing myself between the blank walls with no real holds.

I was an experienced enough free soloist to know that I had to climb cautiously but not too cautiously. If you get too tentative while soloing you’re liable to freeze up at a hard move. After a few pitches I decided that I felt really good. In fact I was having fun. I found a smooth flow. Going ropeless in the chimneys made them feel that much easier. No gear to get in your way.

By the time I hit the upper face pitches I started to feel really in the zone and the whole climb started to become a joy. This was some kind of gift.

I hustled up the final sections and topped out the Black Velvet Wall to a dry wind. Las Vegas shone in the distance before a setting sun. I bounded down the descent trail, eager to arrive back to camp. I wasn’t mad at Kerry for bailing. I wasn’t mad because I realized that his departure had been the source of some kind of great and rare gift bestowed upon me.

It felt special to finish the day in such good style, kind of like pitching a perfect game and striking out the last three batters, or something like that. Yet there would be no screaming audience celebrating the day’s victory. No fist pounds or high fives. No beers even shared. The only thing to greet me was a nearly empty parking lot on a piece of dirty desert across from a gypsum mine in the middle of nowhere. The morning dawned cloudy and cold. It was my proudest climbing achievement to date and I had no one to share it with as Kerry was nowhere to be found. Probably drinking beers in the casinos. And by the next morning, I had already packed and was heading to Yosemite to chase down more dreams on the funds of my experience as a lab rat.

Time has a way of clarifying your hazy abundance of memories and sharpening the focus of those events with a delicate clarity. Things you thought were important at the time sometimes turn out to be not as important as you had once thought. “What it all meant” kind of shit. That was something I have always been searching for and now that I look back at my 20-year-old self chasing down the mountains of my youth, the successes and the failures seem to be one and the same. Significance moves on to something akin to wisdom and experience.

Or maybe I’m just getting old.

It was so important back then for me to climb hard and to some degree it still is. But today it’s the simple memories of roaming casinos searching for cheap beer and cheap food. Selling your body to science and loitering with the riffraff. Waking up in the quiet, chilly breath of the desert to a once-in-a-lifetime comet, and going on to live a day that you could never forget.

superb, well told

Awesome man, I read the whole story then when I read who wrote it I realized I shared a campfire with you last winter at the Obed and listened to you playing music.

There is no way Croft backed off Epinephrine. That route is a million times more secure than stuff he hikes before breakfast.

That was a great story. Was the emo guy Jason Kehl? I’m sure it was. Kerry ended up getting a college degree in engineering and built a solar water heater out of a satellite dish for a hot tub. He climbed in a ski suit.

Excellent! You are as good a writer/story teller as you are a climber. Looking forward to reading more.