On August 23 in Munich, Adam Ondra narrowly beat a really tough field to become the bouldering World Champion. He eked out his victory in dramatic fashion, winning on the very last problem before an audience of 6,000+ people.

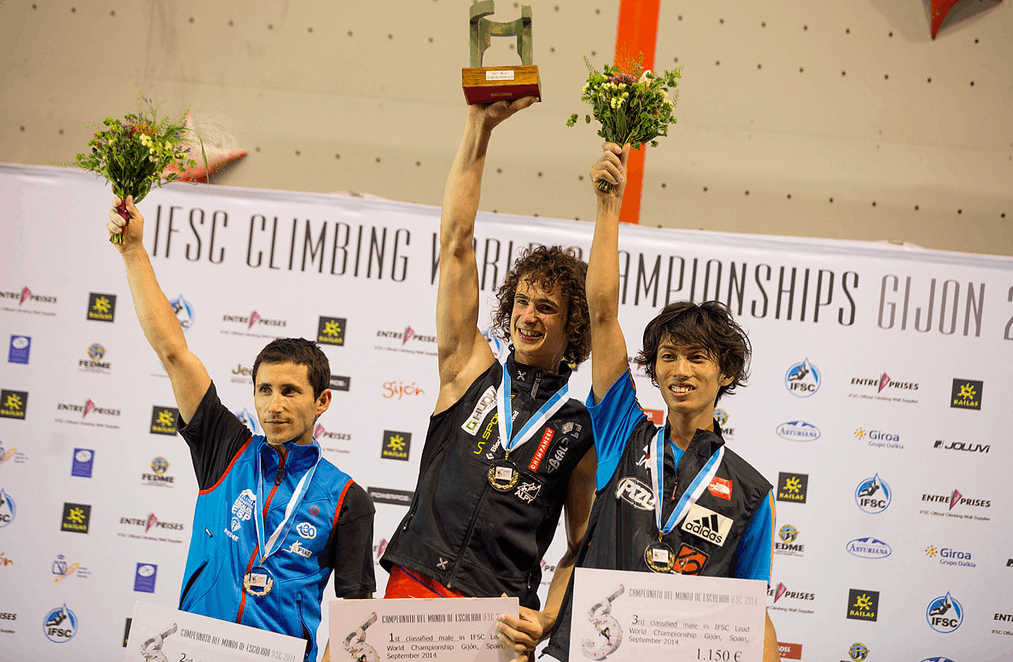

Less than a month later, on September 14 in Gijon, Spain, Ondra won the Lead World Championship, again with a very narrow victory over the indomitable Ramon Julian. By doing so, Ondra became the first person to win both lead and bouldering competitions in the same year.

Lead World Championship: Ramon Julian, Adam Ondra, Sachi Amma IFSC

To simply say that this double victory is remarkable or unprecedented is a huge understatement. Why? Because bouldering and lead (aka, sport climbing) are rapidly becoming very different, extremely specialized activities—so much so that relatively minute differences in body types and training regimens are becoming very important factors for success.

To be pretty good in both bouldering and sport climbing may not be that uncommon … But to be a world champion of both disciplines? Well, that’s remarkable and unprecedented.

Ondra has the greatest climbing ticklist of any living climber. He has climbed the world’s two V16s, all three 5.15c’s, and has onsighted three 5.14d’s. But historically he has had a hard time in World Cups. An interview with Cristian Brenna I posted a few years ago told a cool anecdote in which Ondra, in the wake of a summer defeat to Ramon Julian, expressed his dismay to Cristian by saying, “I even spent the last few weeks training indoors for this!”

“But Adam,” Cristian explained, “Ramonet has been training since February!”

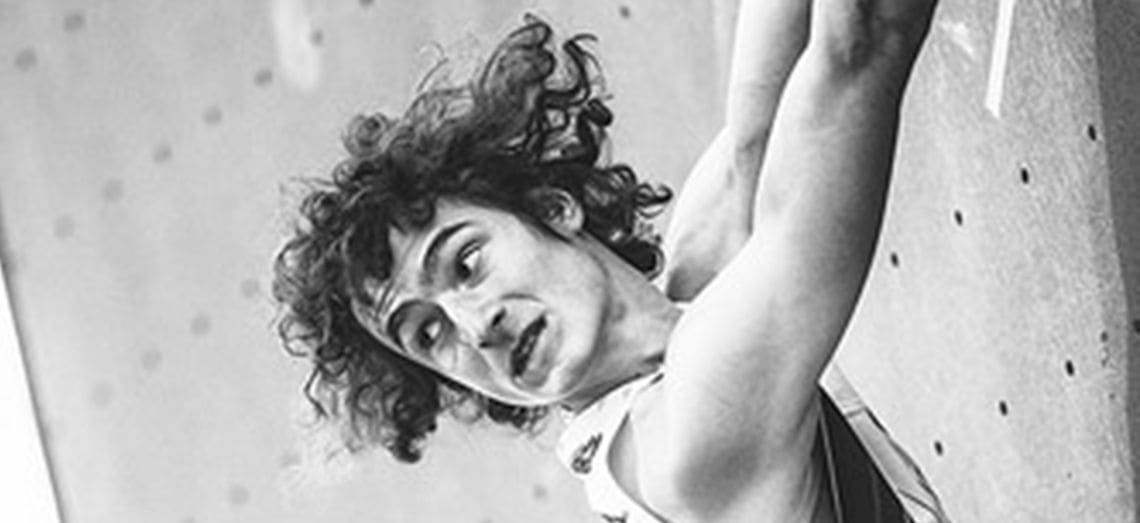

Munich World Cup. Photo (c) Marco Kost

Last year, Ondra boldly stated that he was planning on spending 2014 focused only on competitions. And sure enough, come February, Ondra hit the gym … and hit it hard.

Win in Munich Photo (c) Julian Buckers

The competition season, however, was not without a few errors. In Chamonix, Ondra missed a clip and lost. Later, in Briancon, he came in a disappointing 8th.

But Ondra hit a turning point, gained a confidence boost and, like a 21-year-old Czech Rocky, he charged into both Munich and Gijon and TKO’d those suckers out.

I reached out to Ondra to find out more about his past year spent training in the pain cave … and what it’s like to now bask in the glory of being undisputed World Champion.

Jerry Moffatt wrote in his book, Revelations, “I would have traded all my competition wins for a first ascent.” What was more satisfying: your 5.15c first ascents, or winning the World Championships in both lead and bouldering?

Well, competitions weren’t very satisfying for me in the past, but this time, it was different. It was comparable or even more satisfying than sending Change or La Dura Dura. Because I trained so hard for it. And because I had winning in my mind for such long time.

What was your motivation for wanting to focus on competition this year?

The World Championships were the main goal. Because what is greater in competition than competing against the world?

Besides that, I was just very curious about the training itself. I was also hoping the training would help me with climbing outdoors. But more so, I was very curious to see what effect dedicated training would have on me in terms of gaining the special type of power-endurance that lends itself to lead competition.

Based on my experiences in past comps, I wanted to know if I was just simply too tall and too “heavy” to win lead competitions—not heavy for my height, of course; losing weight would not be wise in my case. But it’s just that the best lead competitors are all very short and very light.

I also view competitions as being confirmation that I trained well. Also, I like the mental part of competing, which is also very interesting to me.

Audience in Munich Photo (c) Julian Buckers

I must say … I really enjoyed the training! The sacrifice, the pain. In the end you just get to climb A LOT during training, so isn’t that great? Compared to working on a project outdoors, you make a lot more climbing moves day to day during a training period.

When you feel like shit, you go training anyways. After 30 minutes, the pain turns into joy. It was interesting see the limits of my body, what it can sustain and how important the mind is throughout this whole process.

My motivation stayed really high throughout the year, and despite my success in Munich and Gijon, I am training hard again to be prepared for the next World Championship. There was never a moment of regret or a question mark for this decision.

When you missed a clip that cost you a win in Chamonix, did you have doubts about your decision to focus only on competition?

It was very disappointing, especially as it was my second comp in a row that I messed up. And Chamonix wasn’t the end of my bad results, either: the following weekend, I placed 8th in Briancon.

But I definitely didn’t regret my decision, because I knew I was in a good shape. The day after [Chamonix], I onsighted TCT (9a) with unbelievable ease. I knew that my comp performance was a mental problem. There was some kind of barrier that I needed to overcome.

This barrier was finally breached in Imst—the fourth World Cup. I managed to win here, despite the fact that we were on a long and resistant wall. That made me believe that a victory in Spain was possible, which was the main goal anyway.

How many hours have you spent training indoors vs climbing outdoors this year?

Starting in February, I spent 3.5 months of training really hard, which consisted of climbing in the gym 6 or 7 days a week, with occasional cragging on the weekends—though I was too tired to perform well.

During these periods, I would spend up to 30 hours per week training: climbing, campusing, TRX. If you add it all up, that might mean I spent 420 hours of really hardcore training this year.

The other 3.5 months were periods of “pre-comp.” … There is always period of hard training followed by a “pre-comp period.” Here, I did only three hard routes a day, and maybe 30 minutes of bouldering or campusing. I rested two or three days a week and climbed outdoors as well.

I spent one week in Spain climbing outdoors, and two weeks in France, with occasional outdoor climbing at home.

When I went outdoors, I enjoyed it very much. It gave me the energy I needed to go back into the gym and train hard. But I didn’t regret that I couldn’t climb outdoors more—I was really focused.

It was a completely different lifestyle, but it was OK as I had to go to school anyways. During the mid-week days I didn’t have the time to go outside due to school. So I trained. I was just super focused on school and training. And each evening, I was just super happy that I did well each day.

Onsighting Il Domani (9a). Photo: Bernardo Gimenez

You onsighted two 9a’s this year. Any other highlights on real rock?

Il Domani was the main goal outdoors and it clicked perfectly. It is one of my proudest achievements outdoors ever. Then, I onsighted TCT (9a) in Gravere, Italy, one day after the unlucky missed clip in Chamonix. And I onsighted an old-school, short and burly 8c+: Super Plafond.

I also climbed Biographie (9a+). It took me more time than I expected, but I had to admit that it was simply a hard route for me, no matter how many times it has been repeated.

These onsights were good preparation for comps. They were fun and good confidence builders. I found that I can go and try to onsight one or two routes, even right before a comp, because it doesn’t take much time. At the same time, I knew I would be well prepared for these onsights. It doesn’t take very long for me to get into the groove of climbing outdoors. And onsighting is all what lead competitions are about.

Lead World Champions Jain Kim and Adam Ondra. Photo via: Holzknecht / Red Bull / Planet Mountain

Why is it so difficult for climbers to excel in both bouldering AND lead climbing?

If you look at the lead climbers, they tend to be shorter and extremely tiny. If you look at boulderers, they tend to be more muscular and often taller. Both disciplines are getting much more different from each other and from their outdoor origins.

Lead comps require special fitness: a type of power-endurance that is very rare to find outdoors.

Bouldering comps, on the other hand, are moving toward problems set on big volumes with double dynos and sketchy slabs. Doing double-dynos and climbing balancy slabs won’t help you at all for lead competitions. And, likewise, having endless endurance won’t help you with doing double-dynos. In that sense, the two disciplines don’t get on very well.

Volumes and double dynos dominate the comp scene today. Photo (c) Marco Kost

For me I naturally have a high level of bouldering power. Even if I take three weeks off, I don’t loose that much. It is within me.

My endurance, however, is very difficult to maintain unless I train super hard. My body has a better constitution for bouldering. And as I said, most of the lead competitors are shorter and (therefore) lighter. My height rarely gives me an advantage in lead competitions, because the route-setters don’t set reachy moves.

If there were a lead competition with a crimp ladder of short moves, it would be almost impossible for me to win because the short climbers would have simply a better body size for that. And they can hang on longer because they weigh less.

Finalists at the Bouldering World Championships Photo (c) Julian Bueckers

For a long time, I thought I could gain better power-endurance simply by climbing a lot of routes. But it didn’t really work. I was getting better, but there seemed to be some kind of barrier that I could never overcome. No matter how hard I trained, I couldn’t hang on any longer on the wall.

I began to understand that if I increased my power, I could make the moves feel easier and I could rest better on the route because all the holds felt bigger. This is why my training for lead included a lot of explosive campusing and bouldering—because I knew I needed it.

But this is also why I didn’t need to train for bouldering specifically. The stronger (better) I am in lead, the stronger I am in bouldering. It is quite simple. The only thing I needed is to get used to was the double-dynos.

Most climbers train too specifically, in my point of view. They need to spend more time adapting to different disciplines and styles, especially with bouldering and its balancy problems.

For me, however, it takes less time to adapt because I have climbed many kilometers of rock in my life—on all kinds rock and different angles. I don’t want to boast, but I think I kind of know how to climb. Anywhere, anything.

What’s next?

I have no clue. I was planning to climb outdoors, but I am unsure now. It might be a pity to be leave the competition scene right now. There are still some things that I would like accomplish in the competition world.

Check out this great gallery from Marco Kosta. Visit his website and check out more of his work.

Perfect article for a machine like Adam.

“It is within me.”

Beast mode achieved.

What about old school offwidths?

I don’t know for sure, but I imagine they almost certainly won’t be a problem.

I’ve never really seen or heard about him doing a lot of crack or offwidth climbing, but he obviously knows how to learn, so he would pick it up pretty quick 😛

At what point will the climbing community do an intervention for him and cut his hair? We need an entire interview with Ondra dedicated to this. Show him lots of before and after photos of people with shaggy hair and then short hair. It’s the next logical step in his progression, I mean, he says it’s not good for him to lose weight, but surely the 10 pounds of hair he’s carrying around would be okay to lose.

“I don’t want to boast, but I think I kind of know how to climb.”

Yeah, I don’t think anyone is gonna argue with that one, Adam. He comes across to me as thoughtful, but very blunt. That’s cool. Nice article.