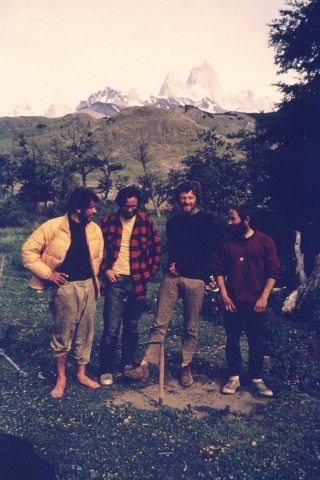

Their trip was successful on almost every level. Upon reaching Patagonia, they spent 60 days living in an ice cave at the foot of Fitz Roy, waiting for a weather window. When that window finally came, they pushed up the flanks of mighty Fitz Roy. The whole party reached the summit on December 20, 1968, in a 30-hour round-trip climb from Camp II. Their new route is now known as the California Route, but was originally called the “Funhog Route.”

Two cult-classic films were made: Mountain of Storms and 180º South

But it was the greater experience of the whole wild adventure, not just the summit of Fitz Roy, that really gave meaning such frivolous acts. This climactic year of 1968 colored the ethos and characters of these five men for the rest of their lives. What they would do and who they became was profoundly a function of this trip. Yvon Choinard and Doug Tompkins each went on to start Patagonia and The North Face, respectively; two of the most influential companies of our time in terms of setting examples of responsible business practices, and influencing the greater discourse about environmental ethics. It’s no exaggeration to say that this one road trip ended up shaping the world from a counter-cultural perimeter into the mainstream.

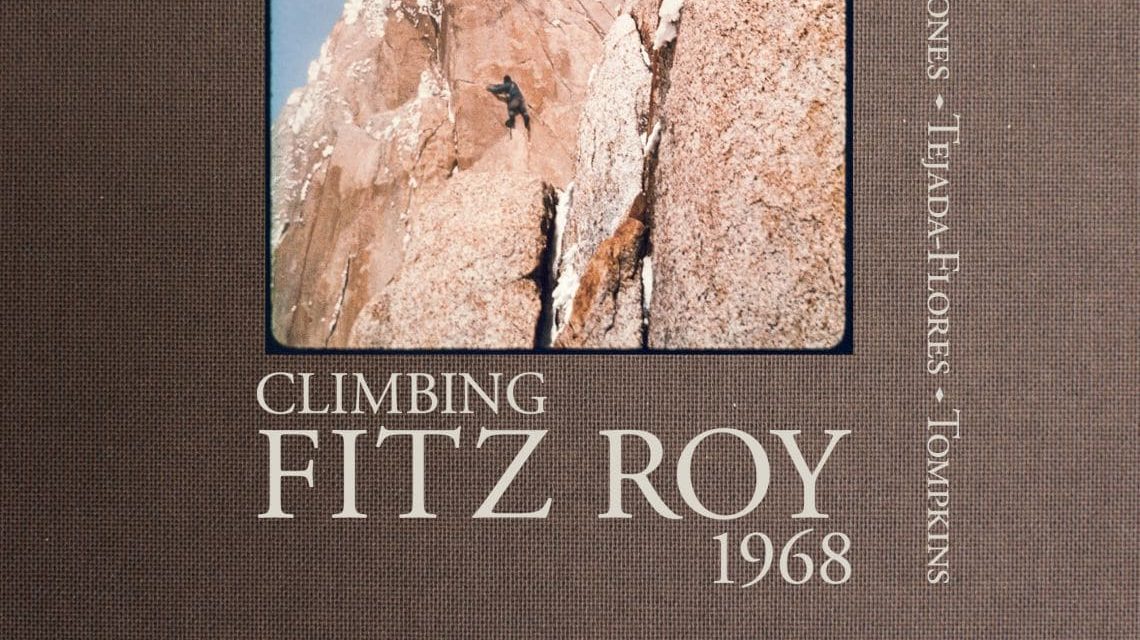

Climbing Fitz Roy 1968 is a fantastic and indespensible new book from Patagonia Books that documents this experience through the words of all five Funhogs, and a collection of haunting imagery that was actually thought to have been lost to a fire. In 1996, Chris Jones, the real photographer of the group, and his wife, Sharon, lost their house to a wildfire. With it he thought he lost his archive of photographs, too. The loss had a deep impact on Jones:

Climbing Fitz Roy 1968 is a fantastic and indespensible new book from Patagonia Books that documents this experience through the words of all five Funhogs, and a collection of haunting imagery that was actually thought to have been lost to a fire. In 1996, Chris Jones, the real photographer of the group, and his wife, Sharon, lost their house to a wildfire. With it he thought he lost his archive of photographs, too. The loss had a deep impact on Jones:

“I began to wonder whether I had really lived through all those experiences. Was I the person, the climber, that I believed I had been? Those events shaped who I was and now they were receding into the distance.”

Several years later, by accident, Dick Dorworth read that Jones’ house had burned down and that their image archive had been lost. Dorworth realized he had the duplicates stored in a storage closet in Shoshone, Idaho. And over the next few months, he meticulously mined them out of a mess of bins. Over three decades after reaching the top of Fitz Roy, the lost images were once again retrieved.

By Chris Jones’ own admission, the images aren’t the most creative or dynamic photos, and I found his explanation why to be very interesting. Climbing was still very much a “new” sport—both in terms of its emerging techniques and gear, but also in terms of its burgeoning, still undefined culture. Jones describes being in Peru and putting a lot of creative energy toward photographing the locals, making stunning images and capturing the beauty of the Andean people. But strangely, that same creative energy didn’t come through when photographing each other. Jones explains:

I think that that is a fantastic assessment that contextualizes these images. They’re not very good. They’re not very creative. But they do document an important moment in time, and lay the groundwork for the ensuing burst of creativity in climbing’s culture, through the written word, and especially through still and moving pictures. Most of all they prove that these experiences were real. And to people like me, they incite a genuine, visceral and emotional response to go out there and create my own meaningful experiences.

With the permission of Patagonia Books™, I’m pleased to be able to publish this excellent excerpt from Climbing Fitz Roy 1968, penned by one of my favorite authors Dick Dorworth. Click here to read “Viva Los Funhogs.”

Recent Comments