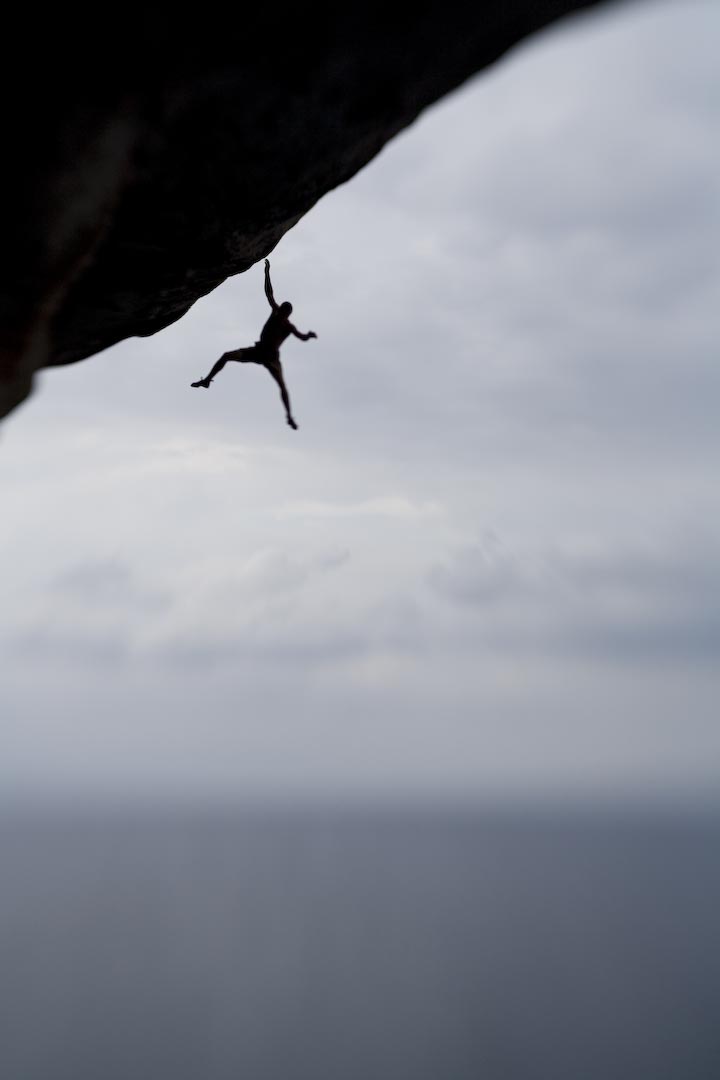

Waves walloped the seaside wall from which I hung—barely, I will add—by my own saline fingertips and wet climbing shoes. The waves struck with such force that mini earthquakes reverberated up through the rock and down my wooden limbs. I could feel a filigree of nerve endings in my body quaking with fear, like the Aspen leaves do, back home in Colorado in an autumnal gust of wind. Don’t think I even breathed. Everything I’d ever learned as a climber was in upheaval, churning in aqueous tumult and thoughtless panic.

You are free soloing and you must not fall. This essential climbing wisdom, engineered into my DNA for the last decade, was stubbornly unraveling.

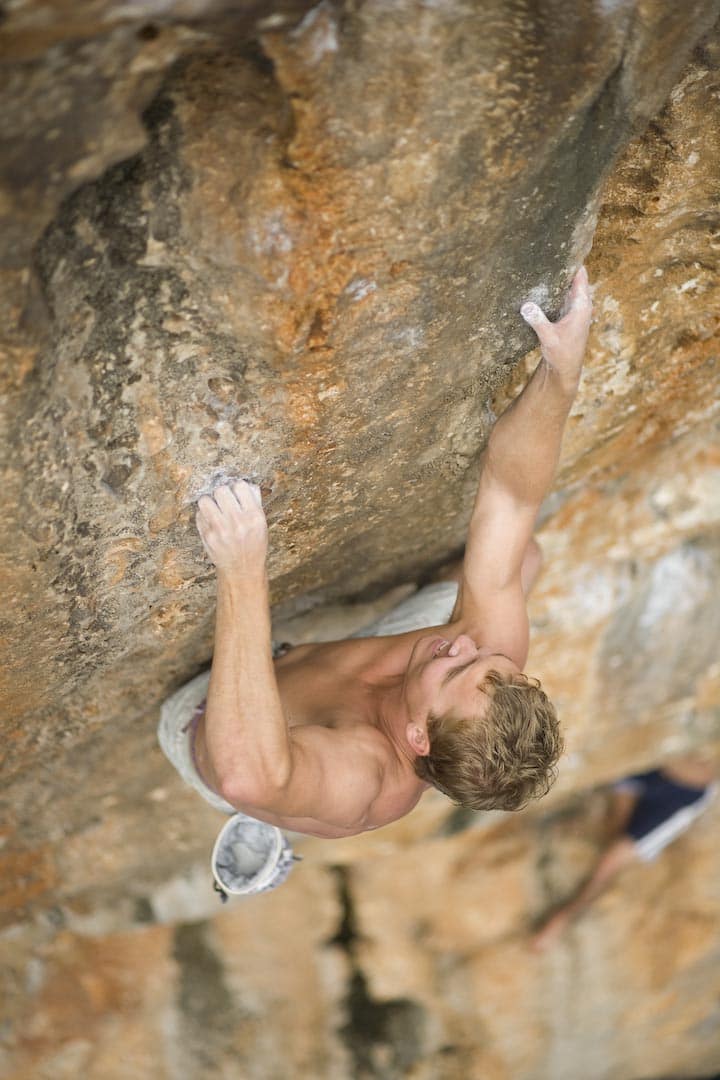

All photos by Boone Speed, unless otherwise noted.

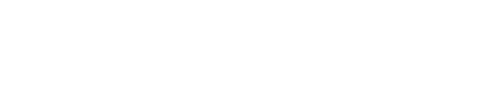

I was soloing 40 feet above a boiling tide, ropeless, mid 5.11 crux. An eclectic group of climbers leaned over the precipice, 20 feet above and to the right of me, cheering and hollering. I realized that even though I was soloing, technically I could fall. What a total, weird twist. I could just let go and drop through the air, screaming and plunging into that big briny drink below.

But somehow that permission to let go, just the simple consideration of it, made everything much, much worse.

Boozy, romantic aspirations of climbing above indigo waters, free and naked but for board shorts, climbing shoes and chalk bag, brought me to Mallorca. I was keen to experience first-hand this subset of climbing that was only then striking the American climber’s radar via recent viral media. Stoked-out videos had appeared of guys like Klem Loskot and Chris Sharma, dynoing like mad and falling away like Icarus de-winged.

This thing they were doing, I learned, was called “deep-water soloing,” meaning that one climbs sea cliffs up to 70 feet tall with no gear, no rope, no nothing but the water below to save you if you fall. Mallorca—an island of bullet-hard orange and black limestone, in the Mediterranean just east of Spain—was THE place to do it.

The Mallorcans, who invented deep-water soloing, have a different name for it; they call it psicobloc (SEEko-block). That literally means “psycho bouldering.” Certainly seemed a more appropriate term to me, mid-way up my first solo.

I was frozen, wondering whether to continue climbing higher, or just jump now and get the whole damn thing over with. I clutched a whale’s mouth of rock and chalked up unremittingly—whatever it took to calm my nerves and break through this fear-stricken catalepsy.

For some reason, a distant memory flashed within: the time I won roshambo and led the first pitch of Zodiac (A3+) on El Cap—my first time aid climbing. The reminiscence wasn’t sparked by any similarities of environment or action. Rather it was a likeness of emotion, a summoning of power. It was that sensation you experience before embarking on any adventure so big and new and uncertain, when you find yourself standing at the precipice of that rabbit hole you’ve been dreaming about for so long, uneasy and scared and still just standing there, pondering the reasons why you’d even put yourself there in the first place.

Then … you either back away in retreat … or you become possessed. By passion, or something like that—as if you are overtaken by some force that is not you. But you like it. It zaps all anxiety, all thought, all doubt, and the only thing left is that fuck-it attitude you need to just dive in and see where the tunnel leads.

I breathed. I climbed. I pressed my toe on a blank smear of rock. I set three fingers on a sloping dish. I laddered through a sequence of delicious handlebar jugs. Soon I was standing on top. I turned toward the oceanic expanse, rose and purple in the twilight, and yelled with all my lungs, releasing myself from this climbing-induced trance, my forearms awash in lactic acid.

I wondered if I’d ever climb on a rope again.

***

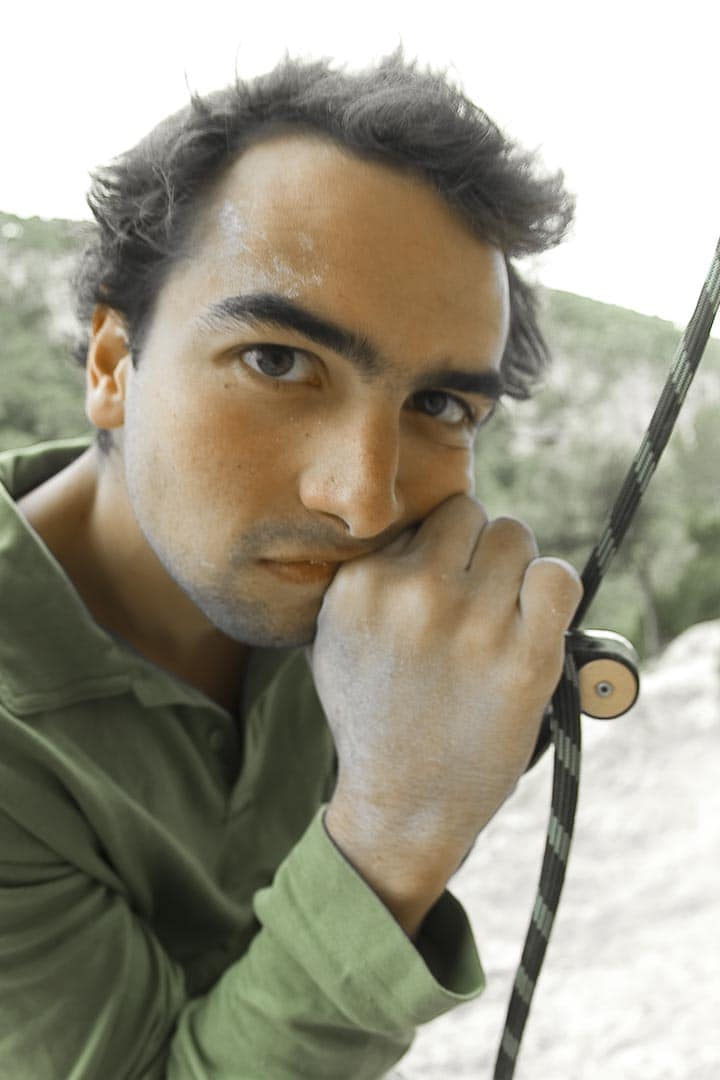

“Mustache Power!” yells Miguel Riera, approaching the precipice of the infamous Diablo Wall on the island’s west coast. The native Mallorcan climber has been working on growing out his very own porno ‘stache, ostensibly for all the ironic reasons someone would ever do something like that. (Beats me).

“Que pasa amigo!” I say, slapping Miguel’s hand.

“You are too white,” he said. “You need some sun.”

You don’t have to be in Mallorca very long to realize that mixing laid-back island beach culture with hardcore rock climbing is one of the prime reasons this destination is so unique.

The Diablo Wall is the most famous spot for deep-water soloing in Mallorca. It’s home to “Loskot and Two Smoking Barrels,” a 5.13 first established by Klem Loskot in 2001. The deep-water solo features an insane all-points-off dyno to a distinctive feature of rock that looks like staring down the barrel of a shotgun. Forty feet up the Diablo wall, a vertical handlebar of limestone, around which you can wrap both hands, bisects a microwave-sized hole in the side of a cliff. This shotgun-barrel hold, in fact, has become one of the most recognizable holds in all of rock climbing. After climbing 40 feet of 5.12, the holds run out and the wall goes smooth and blank. But, six feet above you, is the shotgun barrel. The beta is to crouch on some tiny footholds and jump, launching through the air with both hands and trying to latch the thread of rock or risk a dangerous, wild fall.

I remember watching an early online video of Loskot trying to stick that dyno over and over, his hand never quite owning onto the limestone bucket, which resulted in him spinning wildly and dropping, in dramatic slow motion, down and down and down forever into the water below.

“All the elements are there,” Chris Sharma once observed of Mallorcan deep-water soloing. “The stone. The air when you’re free-falling. The water. And the fire inside.”

Sharma discovered deep-water soloing for himself in the wake of his groundbreaking ascent of “Realization,” the world’s first confirmed 5.15a, located at the French cliff Ceuse. Achieving that single sport climb had taken him four years—a long, mental process that Sharma describes as way too “emotional,” “mental,” and “stressful.” After “Realization” in 2001, Sharma spent the next year looking for his next climbing project. By 2003 he had gravitated to psicobloc because it was, in many ways, the polar opposite of high-end sport climbing. On his first trip to Mallorca, Sharma “flashed,” meaning he climbed first-try, “Loskot and Two Smoking Barrels.” He was instantly hooked. What was alluring to Sharma was the simple experience of moving over rock, without any thoughts of grades, or pressure to succeed.

His mentor was Miguel Riera, known as the “father of psicobloc.”

In 1978 a young Miguel and his friends explored the island for bouldering potential—a strange thing to do at the time. In 1978 there were very few boulderers in the world, let alone on an island of 800,000 people. Even the term “bouldering” hardly existed back then. Climbing was, by and large, all about tackling large objectives with lots of gear; achieving summits “by hook or by crook,” as the aid-climber expression went. Few climbers back then were as concerned with pushing free-climbing movement and difficulty for its own sake.

Photo by Corey Rich / Aurora Photos

But Miguel’s passion for movement, flow and difficulty steered him to the tiny beach-side boulders of Porto Pi. A curious natural progression took place. Miguel and his friends would push each other, not just to climb harder and freer, but also higher. Eventually, they found themselves traversing from the boulders of Porto Pi and onto the adjacent cliff faces hanging over the Mediterranean Sea. They had jumped off these very cliffs as kids, so why not climb them now? The “boulder problems” got longer and higher.

What Miguel had discovered was a bridge between bouldering and route climbing—between risk and pure gymnastic difficulty. Ultimately, what he created was a totally new sport. Psicobloc.

Over the next two decades, Miguel raved about psicobloc to anyone who’d listen, but most climbers were preoccupied with other forms of ascent then in vogue. The 1980s were all about sport climbing. Bouldering held the spotlight in the 1990s. Even Miguel’s original crew drifted away from the sea cliffs and preoccupied themselves by developing sport climbs on the island (there are now thousands of sport climbs of all grades on Mallorca spread out over 50 crags). It wasn’t until 2001 that deep-water soloing really began to get the attention it deserved.

That year, British climber Tim Emmett received an e-mail from Miguel that featured a photograph of the Diablo Wall. What followed was a major congregation of British climbers, as well as Klem Loskot, a totally savage boulderer from Austria with a neck like a fire hydrant and marble-chiseled shoulders. Within a week, the visiting Europeans, with Miguel’s help, had established 26 new routes up to 5.13b.

The American climbing filmmakers Josh and Brett Lowell released a short film called “Psicobloc” about Klem and Tim’s 2001 exploits. The footage included Klem’s ascent of “Loskot and Two Smoking Barrels.”

That single film inspired not just me, but hundreds of other climbers, including Sharma. Beginning in 2003, Sharma more or less made Mallorca his primary home.

“I can’t really climb 5.12s all day at sport crags,” said Sharma recently. “But I can climb all day in Mallorca. 5.10, 5.11, 5.12, whatever. I never get bored with the climbing there.”

In 2005, Sharma completed his long-term deep-water soloing project, “Es Pontas,” which climbs through the steep underside of a prominent sea arch just off the island’s south coast. Though no grade was attached to the route, some have speculated “Es Pontas” to be in the 5.15 difficulty range, which would make it the hardest deep-water solo in the world.

Photo by Corey Rich / Aurora Photos

Sharma’s ascent of “Es Pontas” was featured in King Lines, the best-selling climbing DVD of all time. Numerous articles, television shows and media were released about Sharma and “Es Pontas”—enticing climbers from around the world to visit Mallorca and try psicobloc.

Though “Es Pontas” joins “Loskot and Two Smoking Barrels” as the most famous deep-water solos in the world, suggesting that only high-end difficult climbing is found here, in fact Mallorca is a haven of moderate, accessible and (relatively) safe deep-water solos that anyone, of any ability, can enjoy.

Sharma continues to spend at least a few months every year in Mallorca with Miguel, whose passion for psicobloc has remained as true as in the days he invented the sport. Together, Miguel and Sharma are continuing to explore the coastline on rented sail boats, finding new walls and new routes of all grades around every corner.

Most deep-water solos begin at the top of the cliff. That means you have to down-climb an easier section and traverse over to the route you ultimately want to try. There are frequently “staging” ledges,where you can sit, eat a bocadillo, watch the ocean for a bit, and eventually summon the courage needed to try something hard.

If you fall in, having a rope ladder (usually knotted climbing rope) to pull yourself out is a good idea.

This day we were back at the Diablo Wall. I climbed upside down through an overhanging grotto of wet, slimy jugs. I turned a lip, happy to have the relief of an angle change. However, my precious jugs had grown a grim sense of humor, becoming bastard slopers. I heard the shouts of friends and spectators cheering me on to pull through this 5.12 crux. Now that people were watching me I couldn’t chicken out; I had to go for it. I tossed for a crimp, caught it for a second and my feet swung out from the wall as my core tension went butter soft. I cartwheeled through the air for 30 feet and struck the water on my side.

I could hear groans and laughter before I even broke surface.

I swam over to a ledge and pulled myself out, batmaning up a half-shredded rope. I poked my side and chest, bruised and battered.

“Bad beta,” said a German, who was sitting next to me, and shaking his head.

Deep-water soloing had existed in my head as this free-form thing: no grades, no beta, no nothing. Yet here at the Diablo, there were now full guidebooks to the wall complete with numbers and route lines. Chalk and tick marks everywhere. It was a bit of a let-down, actually. I thought about why.

Sitting on that ledge, I felt privy to an incredible temporal vista. Some part of the extraordinary spirit of deep-water soloing remained visible to me, but it was also apparent that it would not be long for this world. And here I was, lucky enough to see glimmers of the sport in its mercurial perfection but also burdened by truth that I, simply by being there with my guidebook and chalk, was also contributing in some way to its loss.

I decided to let those self-absorbed concerns roll off my back like the water. In reality, I was damn lucky to be there, lucky to be able to try my best in this unique vertical playing field of my heroes: guys like Sharma, Loskot, and Miguel. After drying off, I started climbing up another 5.12, focusing on placing my feet, not overgripping, staying relaxed, breathing well and all the other little things you learn and forget and learn again in your life as a climber. This time, I felt strangely free of fear, completely relaxed. I didn’t hear anyone’s cheers. I was just listening to the sound of my breath over the frothing waves.

The first two cruxes proved to be quite difficult, but I surprised myself by getting through them. I was climbing without feelings of self-consciousness. I was just flowing.

But then, apparently I let my guard down because I botched the last (and least difficult) crux of this route, 50 feet above the water. I grabbed a crimp out of sequence and didn’t down climb to try to fix it. My elbow went up: the dreaded “chicken wing” that indicates forearm fatigue and preludes almost all falls in climbing. My footwork went to shit. I saw a savior jug a mere three feet overhead. I tried to gain it, but fatigue was too great and the top of the wall eluded me as I was suddenly surrounded entirely by air.

It was poor climbing, but in retrospect, I learned more about myself from that single failure than I would have if I had muscled through. A vow to be better next time, or something like that. I still think about that climbing gaff to this day, and it still motivates me to strive to be smarter, better, stronger next time. Next time.

I fell a long, long way—silently and relaxed. And this time, I stuck the landing.

Thanks to Boone Speed for these excellent photographs, which first appeared in Rock and Ice magazine. Please visit Boone Speed’s website for more.

Hey! Really enjoyed reading your experience in Mallorca!

I’ve only been there once and decided to indulge in a guided tour to the Drach Caves (recommendation from a friend) and I was impressed – the atmosphere was surreal.

It was a mesmerizing journey into Mallorca’s underground wonders. And the concert? Truly enchanting.

Maya